The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has declared a "public health emergency of continental security" over mpox as a deadly strain of the virus previously found only in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) spreads to neighboring countries.

Jean Kaseya, Africa CDC's director general, made the declaration on Tuesday, August 13 after consulting with health experts and African leaders, the first time the body has invoked this new mandate since adopting the designation last year.

According to Kaseya, the declaration will enable Africa to lead and coordinate its response and promote the continent's role in global maneuvers. It will also promote "international solidarity," he said, to prevent what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, when wealthier countries prioritized vaccines and treatments for themselves.

Kaseya made the announcement less than a week after telling journalists that he was mulling the declaration. "We don't want to be abandoned again. We are deciding when there is an emergency, and we are speaking with one voice," Kaseya said during an August 8 media briefing, convened a day after World Health Organization (WHO) Director General Tedros Ghebreyesus stated his agency was consulting on whether to declare mpox a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC).

Experts say that the timing of Kaseya's statement signals that Africa is looking for a more prominent role in the fight against the outbreak than in previous public health emergencies.

"There has been some tension between Geneva and African states over whether the region should declare its own health emergency," said Lawrence Gostin, the faculty director of O'Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University in Washington, DC.

We don't want to be abandoned again. We are deciding when there is an emergency, and we are speaking with one voice

Jean Kaseya, Africa CDC

African leaders, he said, see the WHO as "necessary but insufficient" in preparing and responding to pandemics. "Thus declaring a regional emergency is a natural and important way for African countries to work together to contain outbreaks within the region."

Ghebreyesus announced on X that the WHO's emergency committee will meet on August 14.

"The committee will provide me with its views on whether the outbreak constitutes a public health emergency of international concern—and if so, it will advise me on the temporary recommendations on how to better prevent and reduce the spread of the disease and manage the global public health response," he said.

Unprecedented Threat

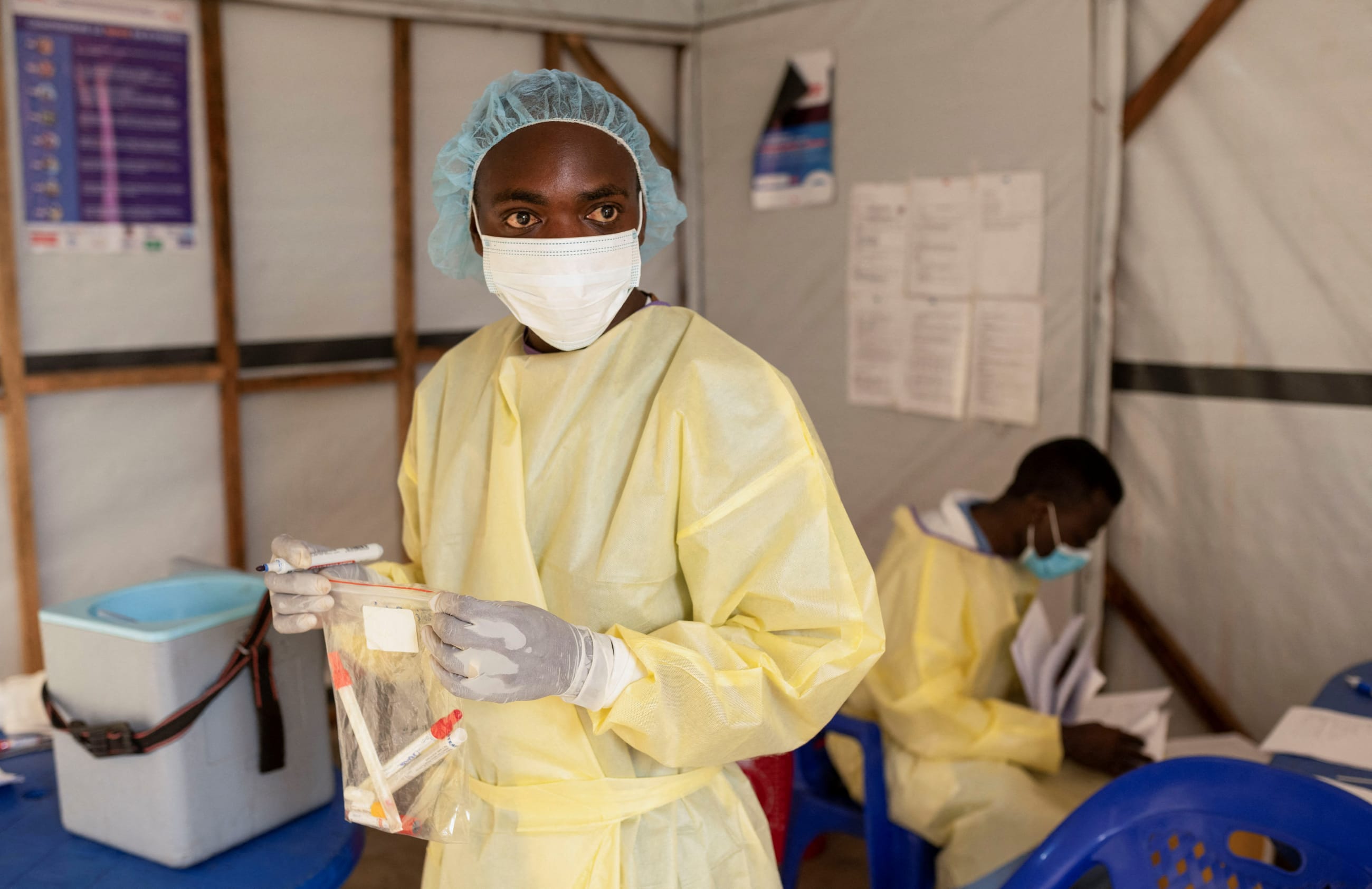

The moves to call emergencies come as Africa's mpox outbreak reaches unprecedented levels. Although the disease, which spreads from close contact, is endemic to a few countries on the continent, more cases have been reported so far this year (across 13 countries in total) through August 9 than were observed in all of 2023.

Several countries where mpox has not previously been seen, such as Kenya, reported their first cases this month, and the Africa CDC estimates that 18 more countries are at risk. Kaseya warned that official numbers are likely an undercount, given that fewer than a third of suspected cases are tested.

The WHO declared a public health emergency of international concern in 2022 when a strain of mpox known as Clade IIb originating in West Africa spread to more than 110 countries, primarily circulating in networks of men who have sex with men. But Africa "didn't benefit from a lot of the global attention," Kaseya said last week.

This time, the most concerning strain is Clade Ib, which has been associated with higher death rates, is spreading more often through heterosexual contact and infects more women and children than earlier variants. Clade Ib emerged in DRC but has in recent weeks been detected in Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda.

To fight mpox, Kaseya said, Africa needs to better understand the epidemiology of ballooning infections and must have access to new treatments and vaccines. Several African countries have established mpox vaccine plans, and based on these documents, the continent needs 10 million doses, he said.

Kaseya said Africa CDC has been able to source 200,000 doses from Bavarian Nordic, which manufactures the JYNNEOS vaccine widely used in curbing the global 2022–23 mpox outbreak, he added. But none of these have reached the continent yet, and regulatory hurdles must be overcome before the vaccines can be administered.

Competing Declarations

Asked last week whether the Africa CDC's declaration would detract from that of the WHO, Kaseya denied that it would. "Our moves will not contradict what WHO does at global level. Dr. Tedros and I are very well aligned," he told journalists.

But public health experts agree that complex nuances dictate the relationship between the WHO and African leaders, which are playing out in these announcements.

"Declaring both a regional and global emergency shines a spotlight on the need for a coordinated and well-resourced response," Gostin said. It "makes sense" to declare a regional emergency, he explained, given that the continent's public health authorities are closer to the people of Africa and can act based on their needs.

But for all the attention they generate, regional and global health declarations have limited power, Gostin said. "The truth is that a declaration of an emergency globally or regionally does not automatically unleash additional powers or resources."

Declaring both a regional and global emergency shines a spotlight on the need for a coordinated and well-resourced response

Lawrence Gostin, O'Neill Institute

Failure in May to reach the Pandemic Agreement during the World Health Assembly is also influencing current events.

"It is highly likely that the Africa CDC is considering this move to position the continent better, particularly in light of how the pandemic treaty discussions have played out," said Alice Beck, policy officer at Health Action International, a Netherlands-based nongovernmental organization.

Pandemic treaty discussions earlier this year, she pointed out, were "marked by a clear divide" between pharmaceutical-rich high income countries and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Provisions to ensure that LMICs that share pathogen data receive benefits from the research and development that results from such data, such as vaccines, remain weak and lack agreement, she said.

This week, Kaseya said what was happening in Africa was a direct consequence of the lack of assistance the continent received when the last public health emergency of international concern for mpox was called.

"When this declaration ended, cases in Africa continued to increase," he said. "We call upon international partners to take [this] opportunity to act differently."