Fewer children are dying from diarrhea than at any point in recent history. In 1990, diarrheal diseases killed nearly 1.7 million children. In 2017, they killed just over 500,000 children. For most people, diarrhea is unpleasant and potentially debilitating, but we do not expect to die from it. Death occurs when severe dehydration causes organ failure. While it's not surprising that rehydration can avert organ failure and prevent deaths due to diarrhea, one of the greatest shocks in the history of medicine was that a simple, inexpensive therapy developed in low-income settings half a century ago would become the frontline treatment everywhere and have the greatest impact reducing death due to severe diarrhea since the dawn of water-borne illness.

That humble therapy, called oral rehydration solution (ORS), is a modest blend of clean water, glucose, and electrolyte salts that was designed to help children absorb fluids lost during severe diarrhea.

If cholera victims were alert and able to drink, oral rehydration solution could reduce the fatality from about 30 percent to just over 3 percent

Developed more than 50 years ago in Bangladesh, oral rehydration solution was once described as "potentially the most important medical advancement of the century." Clinical trials in Bangladesh tested oral rehydration solution for preventing mortality due to cholera in the late 1960s. Cholera is violent and rapid in its symptoms, causing diarrhea and vomiting that can lead to fatal dehydration within 24 hours of onset. Researchers, including Indian and Bengali epidemiologists and physicians, were able to show that if cholera victims were alert and able to drink, oral rehydration solution could reduce the fatality of cholera from about 30 percent when using intravenous fluid therapy to just over 3 percent. Its invention was a watershed moment in the treatment of severe acute diarrhea. Before the 1970s, severe dehydration was typically treated with administered intravenous fluids, somewhat of a Cadillac approach that required access to professional care in a clinical setting.

In contrast, oral rehydration solution is inexpensive, relatively easy to make, and ultimately allowed people to be treated away from clinics and hospitals and just about anywhere, including the home. Since the late 1970s, oral rehydration solution has been a component of global strategies to reduce diarrhea mortality. The United Nations Children's Education Fund (UNICEF) showed that a packet of oral rehydration salts (the solid glucose and electrolytes) could be produced for as little as $0.05 per life-saving packet and mixed and administered by someone with no medical training whatsoever. It reduced the burden on healthcare providers by giving a treatment that mothers or other care providers could give to their children, and it reduced the number of deaths due to diarrhea.

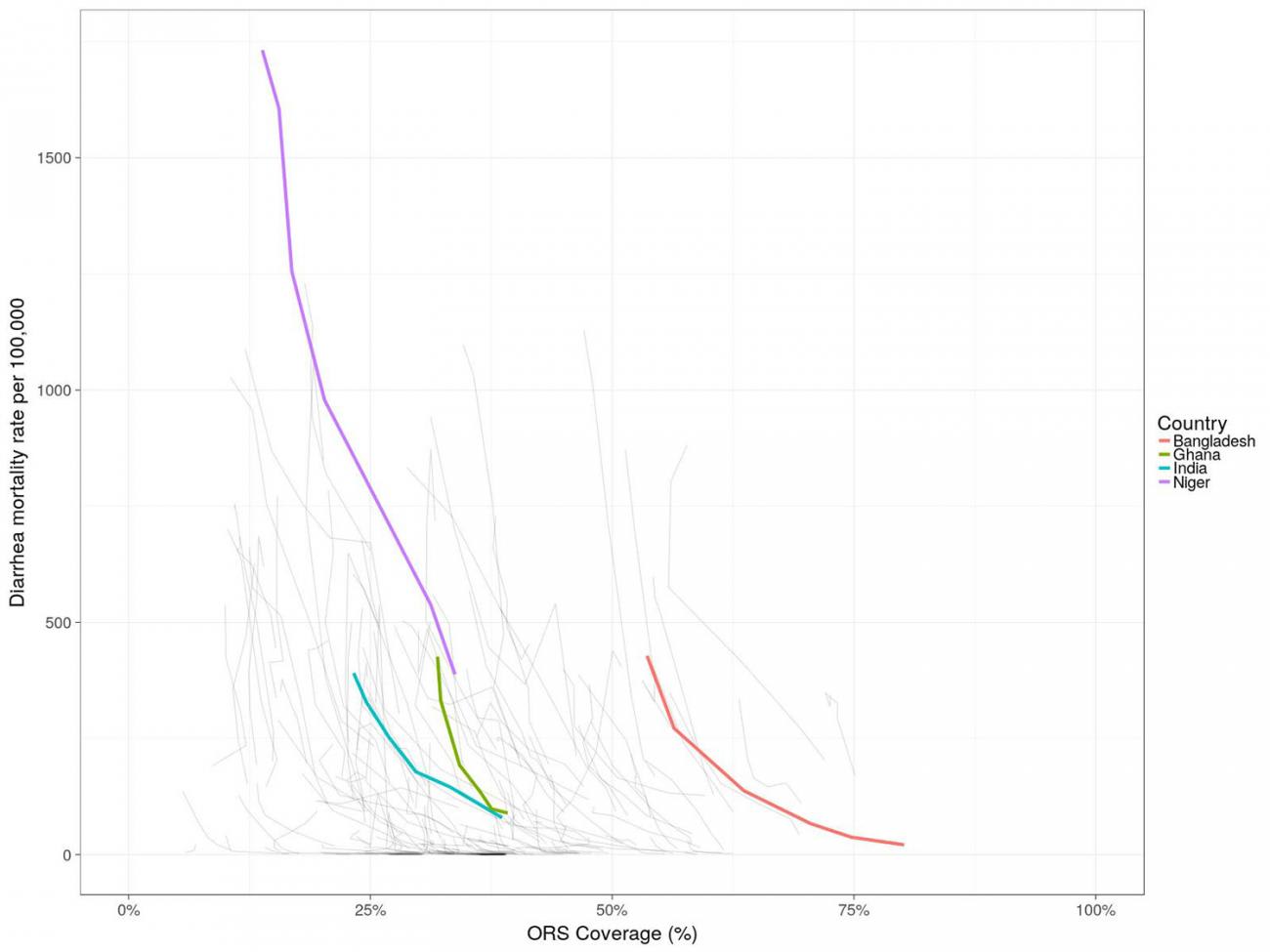

The biological basis for how oral rehydration solution prevents deaths due to dehydration is pretty obvious. Unfortunately, the evidence of just how effective it is at preventing diarrhea mortality has not been rigorously evaluated. A systematic review of the effectiveness of oral rehydration solution found that, at 74 percent coverage, the diarrhea mortality rate was reduced by 69 percent. This systematic review only identified three studies based on quasi-experimental designs, a methodology that does not include randomization in the protocol, which is not typically regarded as reliable or generalizable. Although there is some contention about just how effective it is, the World Health Organization recommends that all children with diarrhea receive oral rehydration solution to help treat dehydration. Still, most children (about 55 percent globally) don't receive oral rehydration solution when they are sick with diarrhea, and many of those children tend to be in locations where the diarrhea mortality risk is already high. This low use of oral rehydration solution could be responsible for nearly 300,000 children deaths a year—more than half of all diarrhea deaths among children younger than five. Put more simply, if every child with diarrhea received oral rehydration solution, about 300,000 deaths would be averted every year.

Children a year could be saved with simple therapy

Discovered in Bangladesh

One of the most successful campaigns for adoption of oral rehydration solution came from where it was discovered. The Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) launched a massive door-to-door campaign to talk to mothers and train them how to make oral rehydration solution at home. The program was wildly successful, eventually reaching over twelve million families, greatly expanded oral rehydration solution coverage, and led to a dramatic reduction in diarrhea mortality in Bangladesh. That was in the 1980s.

Given its ease of use, its low cost, and its proven ability to save lives, one wonders why oral rehydration solution is not used more widely. There are many different reasons. In the United States, the treatment was met with skepticism by some who questioned how something so simple that was designed for low-income countries could also work here, dismissing oral rehydration solution as a treatment for illnesses of the less-developed. The U.S. did not adopt oral rehydration solution for treating childhood diarrhea in the United States until 1992, when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) finally added it to its recommendations. Even after its acceptance, some research has suggested that the lack of awareness of the treatment, both by health-care workers and child caregivers, is a major barrier to its use. Community marketing campaigns using social media and other means to reach people where they connect with their peers, coupled with policy priorities at national and regional levels have been successful in increasing awareness of oral rehydration solution, however.

In low- and middle-income countries, other problems exist. One is that supply falls short in some places. The effectiveness of the solution is also limited by the availability of clean water. This might occur during disease outbreaks, drought, or lack of access to safe water sources. Rehydration with contaminated water can expose people to further infection. Lastly, oral rehydration solution doesn't taste particularly good. It has a strong salty flavor that is rejected by many children. Unfortunately, adding flavors like juice may change the chemical properties of the solution, making it less effective for treating dehydration.

Despite these challenges to uptake, some research suggests that greater coverage reduced diarrhea mortality in children under five by between 4.8 and 8.4 percent since 1990. In 2019, the World Health Organization added co-packaged oral rehydration salts (a solid version of the glucose and electrolytes in oral rehydration solution) and zinc to its essential medicines list for children, ensuring that it is recommended as a foundation of medical treatment. The promise of universal coverage of oral rehydration solution should be the goal of the international health community and if reached, we can expect the impacts to be truly transformational, perhaps one of the most important expansions of medical care in the early 21st century.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author is employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which leads the Global Burden of Disease Study. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.