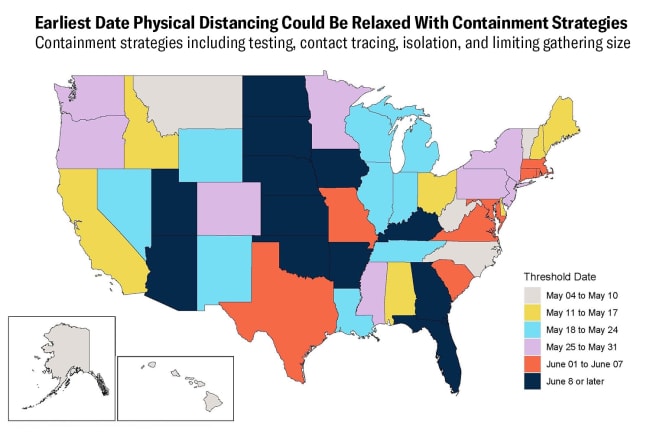

Many states across the United States are planning when and how to ease physical distancing restrictions, while others have already begun to ease them. Americans are worried about their safety—according to a recent Qualtrics poll, two-thirds were uncomfortable returning to work. Indeed, in those states where COVID-19 infections continue to climb, or have not declined for fourteen days straight, reopening could lead to a rapid resurgence of the virus, wiping out progress made to date at great expense to our economy.

As of May 15, IHME estimates that 147,040 people in the United States will die by August 4, 2020 due to COVID-19

Easing of physical distancing and increased movement are major reasons why the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) recently revised upward its projections of COVID-19 deaths. IHME now estimates that 147,040 people in the United States will die by August 4, 2020. This number could climb higher still if more states open earlier than public health officials recommend. With more than 35 million U.S. jobs lost during the pandemic, state leaders are under enormous pressure to strike a balance between saving lives and helping people pay the rent and feed themselves. As policymakers make these difficult decisions, IHME's updated models aim to help them monitor key indicators on COVID-19 in their states.

Movement, testing, and infections

For states that are planning how to reopen as safely as possible, and for states that have already reopened, it is crucial to monitor how much the population is moving around ("mobility"), and how well testing is keeping pace with the likely number of infections in the community ("estimated infections"). Mobility indicates increased physical contact, which can drive up infections.

If testing can't keep pace with the number of infections in the community, it will be very easy for coronavirus infections to increase

However, we are not sure how much rising mobility will increase the risk of disease transmission, but the new data that is rolling in will start to provide more clues. Rising temperatures, people standing six feet apart, and mask wearing may all help mitigate the risk of infection as mobility increases in the United States. Testing drives down infections as those who test positive self-isolate, and their contacts are traced through sound public health efforts. If testing can't keep pace with the number of infections in the community, however, it will be very easy for coronavirus infections to increase, potentially leading to a large surge in deaths and greater demand on hospitals.

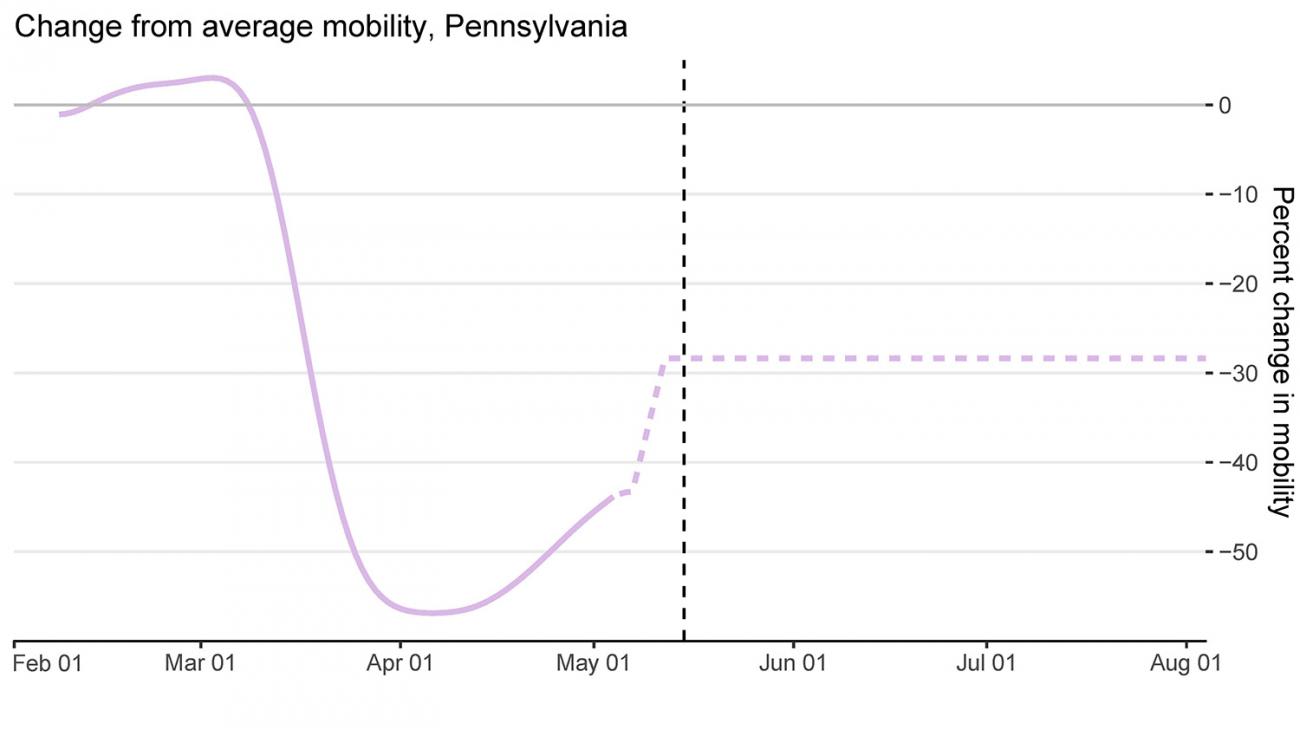

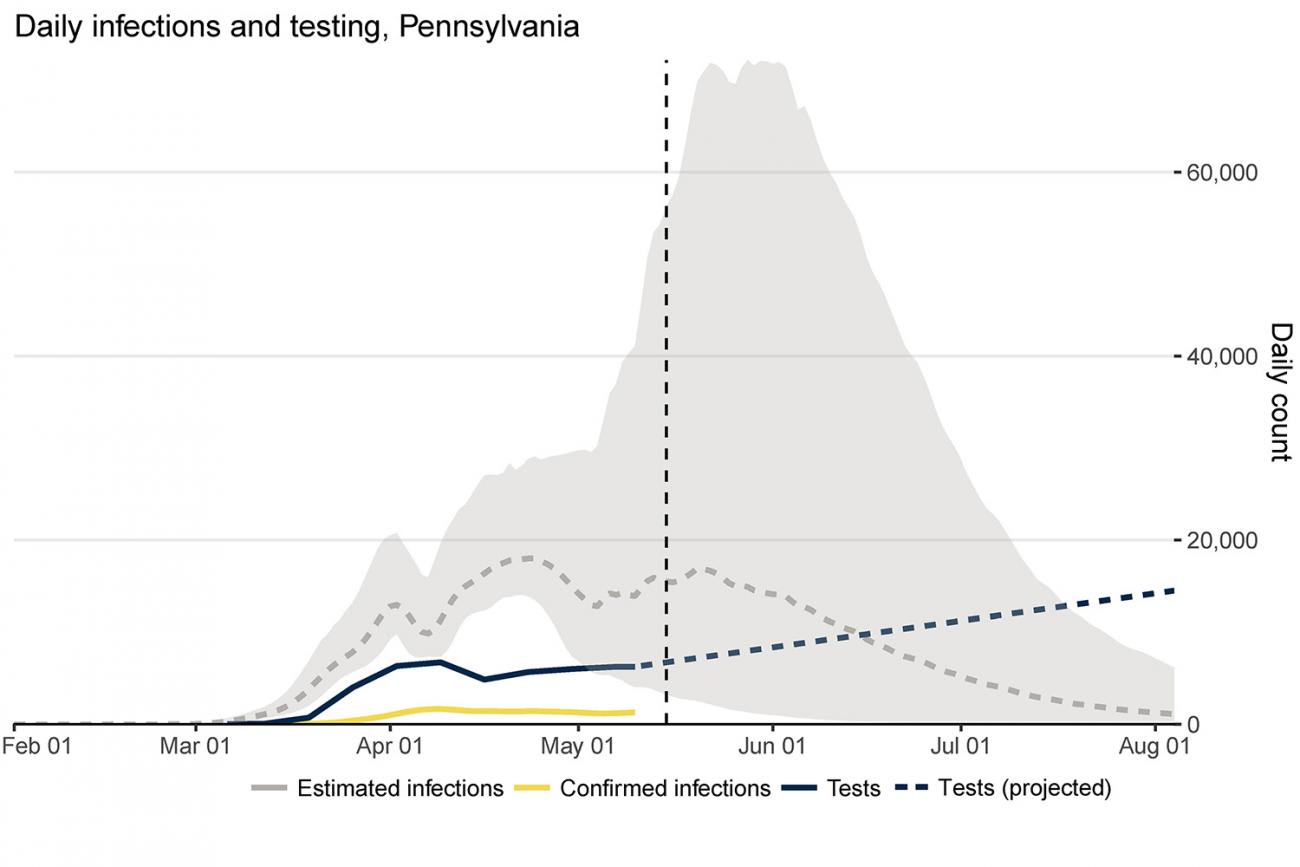

People are Moving Already in Pennsylvania

Take Pennsylvania for example. Since two physical distancing mandates expired on May 8, people are starting to move around a lot more, which is likely to increase the spread of coronavirus. According to IHME's estimates, as of mid-May, mobility has risen by almost 30 percent since early April. Further complicating matters is the risk that the virus could spread even faster than it is now, undetected by the state's testing infrastructure. In Pennsylvania, infections are estimated to be more than double testing levels currently. These trends are worrisome, indicating that any virus surge may be hard to detect until the death rate rises dramatically, which could stress hospitals and lead officials to re-impose physical distancing measures, a grave setback for the economy.

Most troublesome is that states may have to pay a high price—large numbers of lives lost to COVID-19—as the cost of reopening. Massive increases in testing in Pennsylvania could help reduce the risk of resurgence of the virus, as could efforts to reduce mobility.

IHME projects that COVID-19 deaths will remain elevated in the state for much of the summer. I hope that these projections will be too pessimistic—now, many people are being careful to protect themselves against coronavirus as they leave their houses. Perhaps all of these efforts will be enough to counteract the risks of increased physical contact. As time goes on, the data will reveal how much removing physical distancing measures affects disease transmission.

California

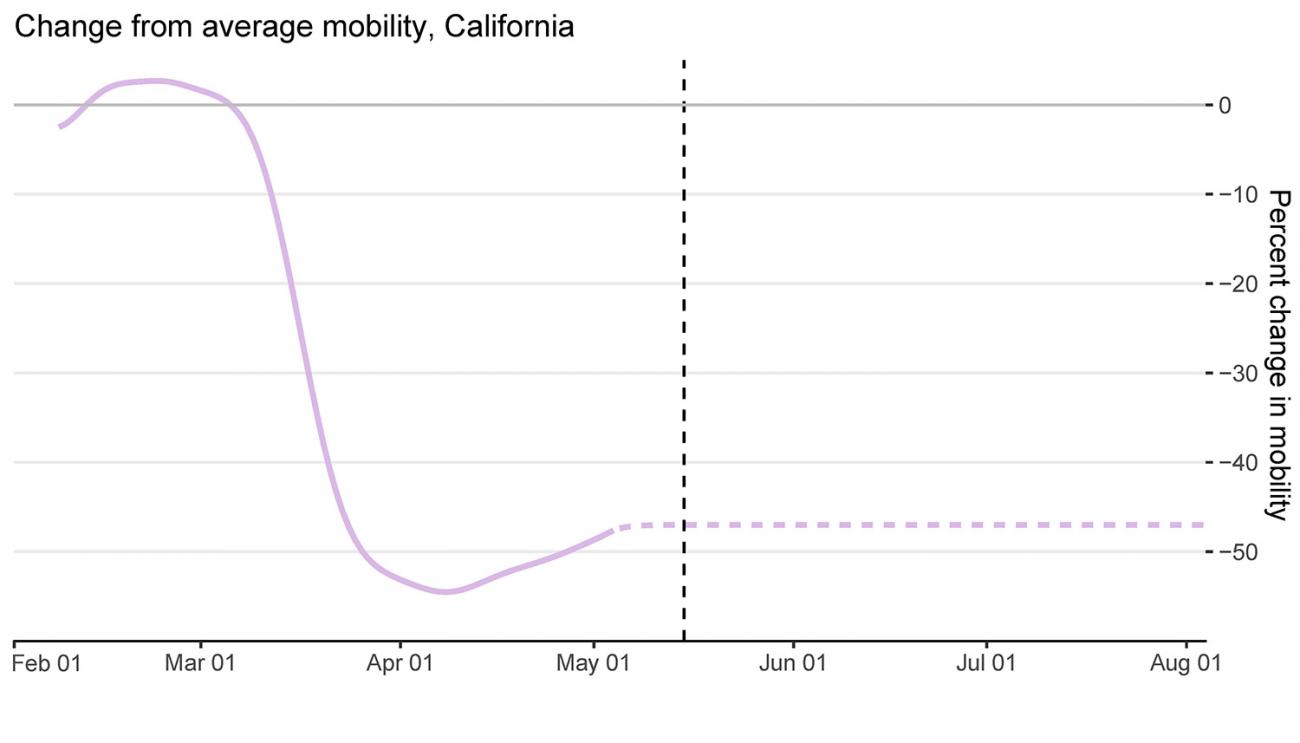

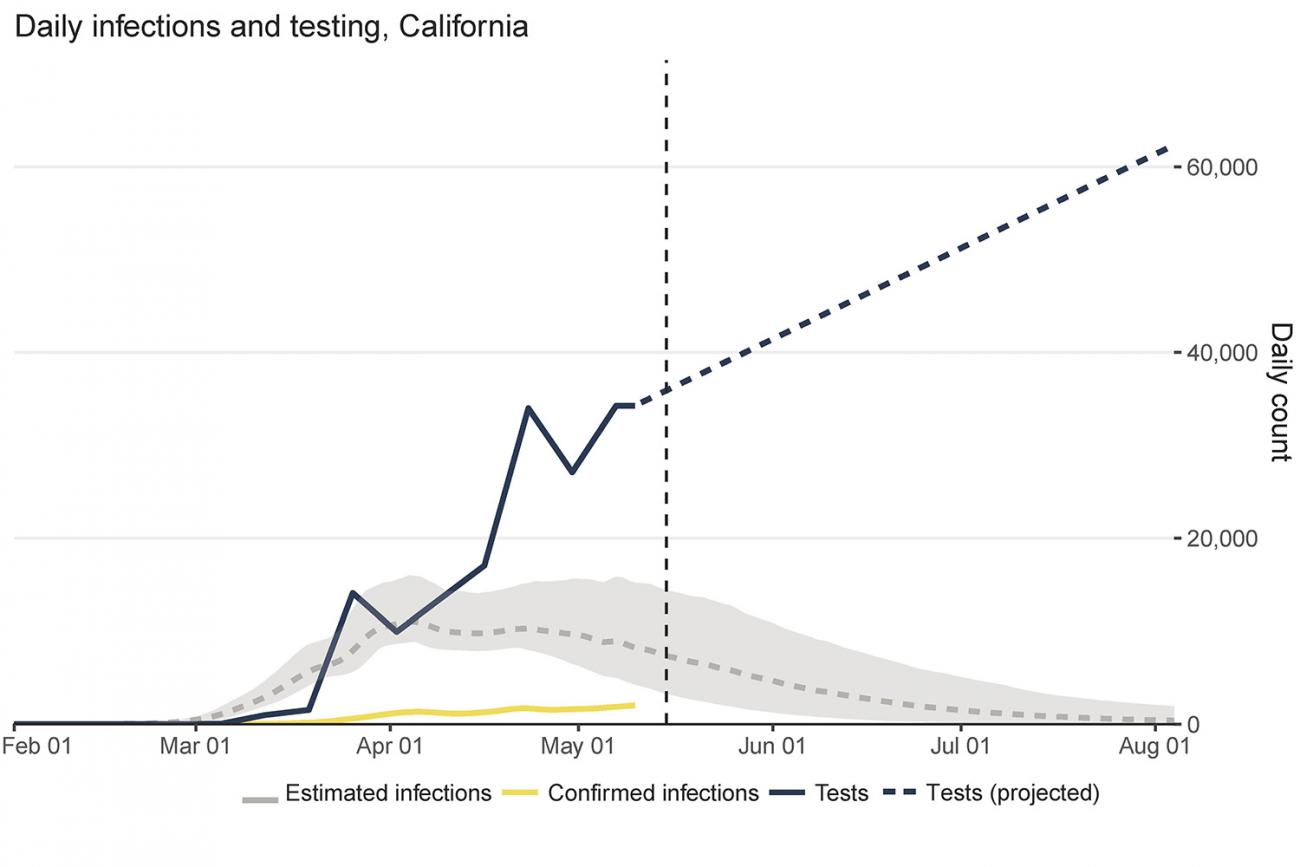

In contrast to Pennsylvania, California has not yet begun to ease physical distancing measures. Mobility has dropped by more than 47 percent since early March. IHME's model, which assumes California's physical distancing measures will stay in place until August 4, projects that infections and deaths will decline steadily, dropping by late June. As of mid-May, testing in California was nearly five times greater than likely infections. Thanks to decreased mobility and ramped-up testing in the state, it is well-positioned to reduce the risk of resurgence once it reopens.

IHME is making these forecasts with the purpose of helping policymakers plan for the weeks and months ahead. When using IHME's forecasts, it is important to keep in mind that the foundation of IHME's predictions is data—a major difference from other COVID-19 models—so the predictions change frequently as new data come in. IHME's data-driven approach is spurred by the desire to let the data teach us how this virus operates instead of making assumptions.

The world is learning a lot about COVID-19 as the pandemic evolves. For example, in many places that experienced coronavirus pandemics earlier in the year—such as locations in China, Italy, and Spain—COVID-19 deaths fell much faster than they have in certain U.S. states, where deaths have stayed at a higher level for a longer period of time.

The updated forecasts also take into account the impact of four main factors on disease transmission. In addition to mobility and testing, IHME incorporates the effect of temperature and population density. Higher temperatures decrease transmission, while higher population density increases transmission. While mobility and testing have a stronger impact on transmission compared to temperature and population density, all four factors help IHME get the most accurate picture of how COVID-19 trends are likely to evolve in different locations.

States can use our tool to monitor changes in mobility to understand what additional measures may be needed

America is eager to move past COVID-19. But the virus is far from gone, and its history has yet to be written. The longer states can discourage people from coming in contact with one another, the more transmission of the disease will decline. States can use our tool to monitor changes in mobility to understand what additional measures may be needed. If states succeed at driving down transmission, public health measures (testing, tracing, and isolation) have a much better chance of stopping the virus in its tracks. Testing must increase to reach levels well above infections—you can view these trends in our tool. States should be aiming for rapid, high-quality tests that deliver results within six to twelve hours; tracing contacts within twenty-four hours, and testing all of the contacts.

Whatever decisions state leaders make when weighing the costs and benefits of physical distancing, it is crucial for them to understand how fast the virus is spreading, and what factors are speeding or reducing its spread. The goal is to avoid even more casualties and overwhelmed hospitals. While many states' decisions to reopen so soon increase the chances of a resurgence of COVID-19 in the United States, IHME hopes that these forecasts can help policymakers keep their states as healthy as possible.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author is employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which produced the COVID-19 forecasts described in this article. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.