On October 7, the governing board of the new World Bank-hosted Pandemic Preparedness and Response Financial Intermediary Fund (PPR-FIF) meets for the second time. The centerpiece of the Biden Administration's health security agenda, the fund will open its first funding window in November with a planned "launch" at the Group of Twenty (G20) meeting in Indonesia the same month.

The board meeting takes place under the shadow of the controversy over David Malpass, the World Bank's imperiled president, who is rightly under attack for his professed uncertainty about the role of fossil fuels in climate change. Malpass has attempted to back away somewhat from these comments in a statement to World Bank staff, but his waffling about climate change isn't an aberration. The disconnect between the lofty rhetoric of the bank's commitment to "reducing poverty, increasing shared prosperity, and promoting sustainable development" and the realpolitik of the institution and its leader is pervasive. It is threatening the PPR-FIF. The board needs to take immediate steps to put distance between the new fund and the institution it sits in.

The governing board of the new World Bank-hosted Pandemic Preparedness and Response Financial Intermediary Fund meets under the shadow of controversy

To start, at its meeting, the board should take decisive action to ensure that the majority of PPR-FIF funds are ring-fenced for the country-based work that is one of three focal areas for the new fund. Since the money cannot go directly to countries, the board needs to ensure that it flows through entities that have a track record of success and accountability and not via the World Bank's lending arms, that are, like Malpass himself, self-preserving and have a dubious record on climate change and pandemic preparedness.

The United States government's blistering pace for the fund's launch is motivated more by the concern that U.S. commitments must be banked this fiscal year than by the urgent need to fund an ambitious, expansive pandemic-prevention agenda via a technically sound, transparent institution that is accountable to directly affected communities.

The headlong rush to launch the fund has, so far, been characterized by a loose approach to priority setting. Board members are, according to several sources we have spoken with, receiving emails asking them for their input; the result is something of a brain dump about what should be prioritized for funding, with everything from "One Health" to surveillance to health workers in the mix. All of these are important, which is why a considered, technically rigorous, and participatory discussion about what this funding window should prioritize for investments—and where it should operate—is much needed. On October 7, the board will reportedly decide on terms of reference for a Technical Advisory Panel (TAP) that will be responsible for reviewing proposal requests. This TAP needs to include civil society representatives from groups that are directly affected.

In lieu of a true participatory approach—and in light of the enormously high stakes of this effort if the first funding round doesn't show impact and build trust—the fund itself will likely fail.

There are two steps that we urge board members to consider on October 7. And a third action that the U.S. government, as the World Bank shareholder that backed Malpass's bid for president during Trump's administration, should take soon.

Step One: Allocate the Majority of Early Funding to "Strengthening Country-Level Capacity"

This is one of three areas the FIF will support, along with "Build Regional and Global Capacities" and "Provide Technical Assistance, Analytics, Learning and Convening."

We propose a 70-20-10 split in order to ensure the bulk of funds are delivered to countries, with another 20 percent going to regional and global capacities, and the remaining 10 percent earmarked for technical assistance. An additional requirement would ensure that technical assistance prioritize indigenous expertise, starting with well-established and trusted agencies, such as Africa CDC.

The first set of investments that come from the FIF board will send a clear signal that this fund is on the right track. Skewing in any other direction–for example, toward regional and global capacities that disproportionately benefit high-income countries—while low- and middle-income countries wait at the back of the queue would be bad for impact and a red flag.

Only by prioritizing interventions that expand "country-level capacity" will low- and middle-income country (LMIC) trust in the World Bank be built. It has failed spectacularly in its recent pandemic prevention investments, and in the United States, where across COVID-19 and monkeypox it proved incapable of making and executing plans that meet country needs in a timely, responsive manner.

It has only been five years since the 2017 launch of the World Bank's Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF), a financing mechanism designed to ensure that high pandemic-risk countries received immediate resources to respond to outbreaks when they occurred. The PEF mobilized a combination of cash resources and bond-based insurance–delivering interest to bond investors, then holding those funds in reserve for payouts to countries who bought in to the pandemic insurance.

The PEF failed to deliver and was shuttered in 2020. Its criteria for paying out against insurance claims were set in ways that protected investors instead of prioritizing swift action. Risk-mitigating criteria, such as a stipulation of 250 confirmed deaths in one country—along with an additional twenty confirmed fatalities in a neighboring country—protected investors and led to egregious delays in disbursements to fund timely, life-saving interventions. Those criteria applied to the 2018 Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) meant that neither DRC nor neighboring countries subscribed to the PEF received any support for many months after the outbreak began. If the same PEF criteria were applied today, Uganda would not be eligible for any assistance with its current Ebola outbreak, a strain that the current licensed vaccine does not protect against.

Only by prioritizing interventions that expand "country-level capacity" will low- and middle-income country trust in the World Bank be built

Step Two: Award Proportionately Invested Funds to Entities That Can Deliver Country-Level Impact

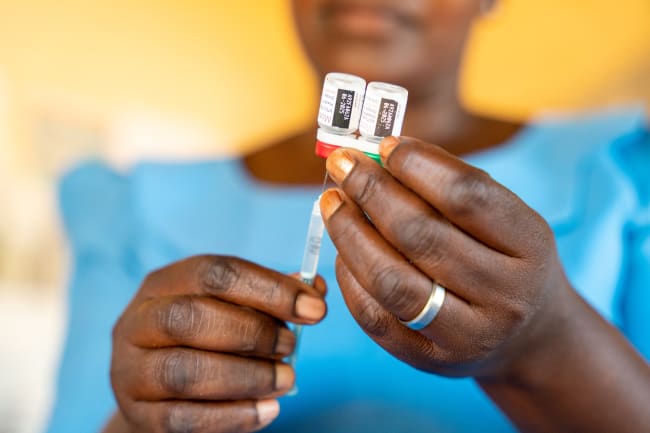

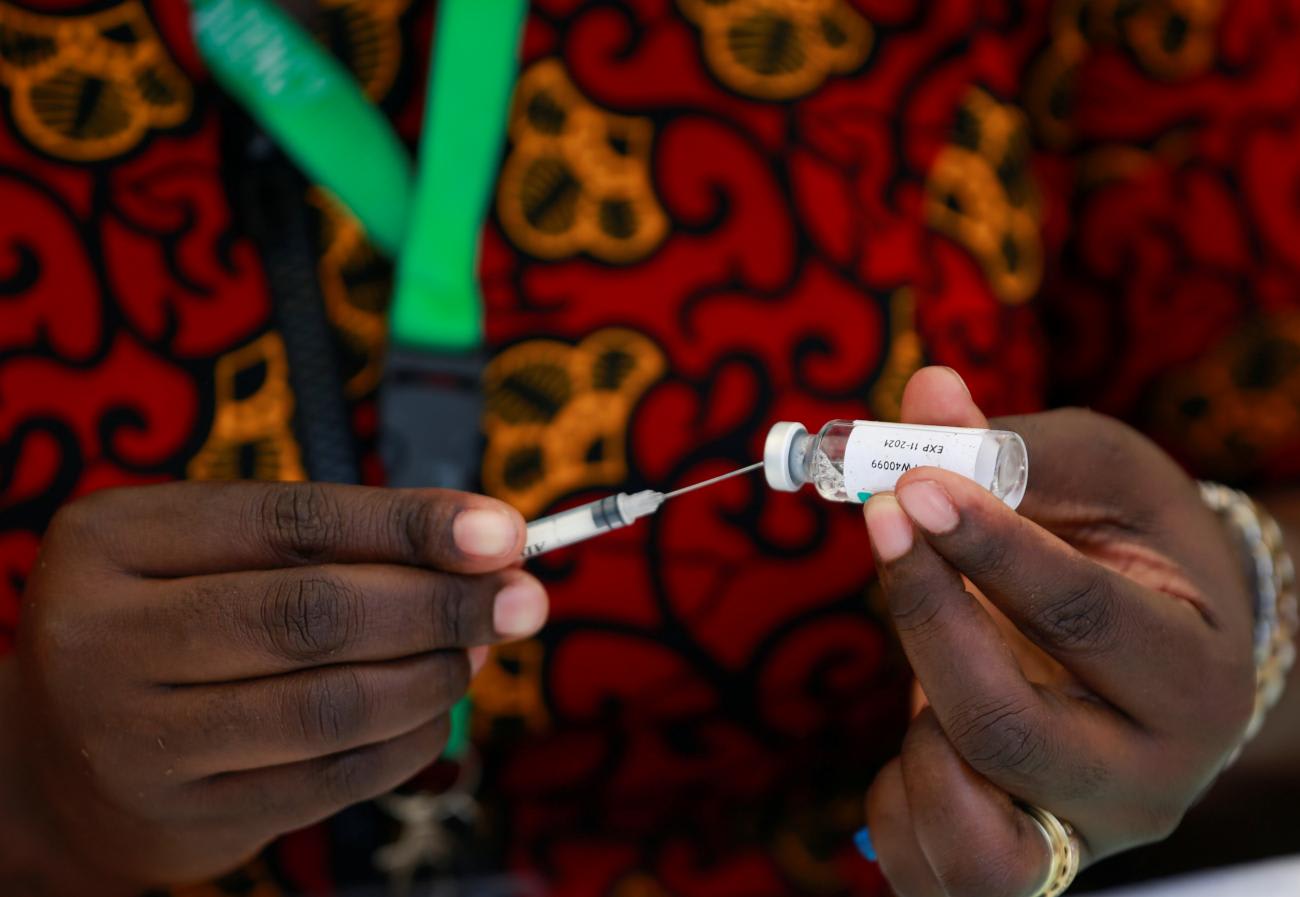

There is a world of work that can be funded under the rubric of "Country-Level Capacity." There are clear gaps in pandemic preparedness and response capacities, including well-funded, trained cadres of community health workers. There is also a need for predictable, high-quality supplies and services that meet basic health needs—that are person-centered and earn trust—and serve clients who come to the clinic with an unusual fever, rash, or respiratory symptom. This will enable early detection and action during the next outbreak. Other priorities should include the development and maintenance of robust, meaningful consultative processes with civil society and communities that the board has already decided must be documented and described as part of country eligibility for submitting proposals.

Many World Bank FIFs typically pass money on to the bank's own lending arms—multilateral and international development banks–whose investments in COVID-19 social protection and public health responses are turning out to be hard to track. It is even harder to evaluate the benefits to the poor and others most affected by pandemics.

Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs)— regional lenders funding development projects around the world—should not be first in line to receive these funds. In fact, we argue that a FIF driven by evidence of pandemic preparedness and response impact should disqualify them from eligibility. The FIF's new Operations Manual states that the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, along with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), could be included as fundable entities prior to the FIF establishment (ie: before the funding window opens, provided the board agrees to "accredit" them via a waiver granted in time for that funding window).

The Global Fund board will soon meet to decide whether the multilateral war chest, which recently fell short of its replenishment goals, even wants to take this on. It's therefore crucial for the FIF board to communicate that funds will be dispensed with streamlined bureaucracy and accounting procedures—so the Global Fund and other entities, such as Africa CDC, are disincentivized to participate.

The Global Fund has a proven track record of working in high-risk settings with flexibility and responsiveness to country priorities. An independent G20-commissioned panel recently concluded that risk-averse lending and investment approaches have been a major barrier to the World Bank's affiliated IDBs and MDBs, achieving impact on important aspects of pandemic preparedness and response. No one knows this more than LMIC governments. The biggest risk would be to put PPR-FIF funds into risk-averse banks that then pressure countries to adopt unambitious or irrelevant plans.

Find the World Bank a Leader for the Interconnected Battles Against Climate Change and Pandemics

Based on its recent track record of pandemic and broader health investments, the fact that the World Bank is hosting the FIF is cause for incredulity, to say the least. During the first half of 2020, the World Bank received six times more in debt repayment from the poorest countries in the world than they received in disbursed COVID-19 emergency funding. It still refuses to participate in a sorely needed program to suspend debt servicing and has been criticized for its lack of transparency in COVID health spending. But World Bank President Malpass's statements clearly question the role of fossil fuels as the cause of climate change and bring the bank's credibility to the breaking point.

The Biden Administration should heed former Vice President Al Gore's call to remove Malpass. Moreover, the U.S, government should articulate—as should Gore–that Malpass's leadership could imperil the pandemic preparedness agenda as well as an effective climate response. The geographies where zoonotic events are most likely to take place include the low- and lower-middle income countries—where people will suffer disproportionately as the planet warms.

If proficiency in responding to ongoing outbreaks—including deploying vaccine and medical supply stockpiles, solving manufacturing and production challenges, supporting trust-based relationships in communities most in need (with hard requirements for their participation)—is a priority, then the United States and the World Bank will need to be allocated to observer-only roles. If global health and pandemic preparedness leadership were earned rather than purchased, the U.S. government would be on the sidelines. Instead, it is in the driver's seat, urging speed.

In an ideal world, global public health decision-making would be executed by a meritocracy, including those most affected by pandemics. In the real world, the PPR-FIF and its champion, the U.S. government, must earn trust as it makes decisions about what it funds, who it funds, and who will oversee this essential enterprise.