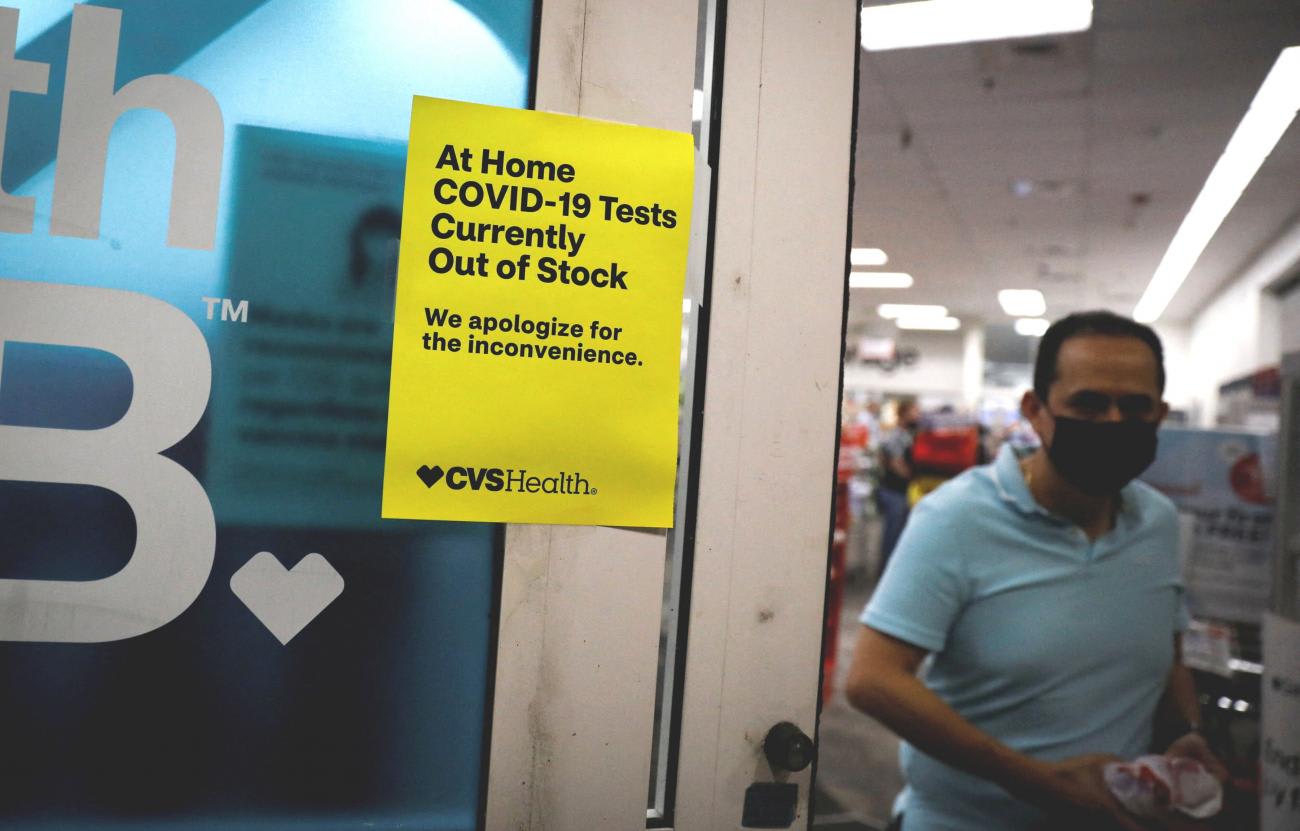

Up until a couple of years ago, most Americans had not heard of the term "supply chain" and rarely thought of shortages. Then the COVID-19 pandemic began, causing people to hunt for masks and hand sanitizer, only to find themselves in front of empty store shelves. Supply chain shortages became common for other items—everything from cars to furniture. Now, there are many concerned parents who are coping with an infant formula shortage. The problem of shortages in crucial goods is not new, however. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has been wrestling with ways to anticipate and alleviate shortages of drugs and medical devices for many years.

Shortages can arise from many causes. In a 2019 report on drug shortages, the FDA identified three primary causes: insufficient incentives to produce unprofitable drugs, insufficient reward to invest in systems that would prevent compliance issues, and logistical and regulatory challenges that make it difficult to recover from a shortage.

To see how these causes interact, let's imagine a hypothetical drug manufacturer that makes an important drug that has a small profit margin. (The drug would be a generic drug that no longer has any applicable patents.) The company has made the drug in the same facility for 20 years, and although there have been no recalls or FDA compliance issues, the head of quality makes a recommendation to invest in expensive new equipment. There is no timetable for when the equipment might deteriorate; it could happen in year 20 or year 40 or never. Given the profit margin and lack of a current compliance problem, or problem with the quality of the manufactured product, the company decides that it is not feasible to make the investment.

Sure enough, five years later, the equipment wears down enough that it produces particulates that become part of the drug. The company conducts a recall and informs FDA. FDA then faces a choice—shut down the facility (in which case there is a shortage), let the company continue to operate, or seek product from an unapproved source that may present its own risks. The agency and the company agree on a middle course—the company makes some improvements that allow it to make a safe and effective product, but under increased scrutiny from FDA, perhaps using an independent consultant. This middle course proves to be a band-aid—the particulate problem recurs, which leads to more recalls and FDA inspections, more resources on quick fixes and consultants, and the agency continues its search for a more reliable source of the drug.

Cycles like this one have occurred frequently over the past 20 years. Also, shortage risks have been exacerbated by the increased prevalence of unreliable suppliers from outside of the United States who manufacture finished drugs and drug ingredients. As the Biden administration recently explained in a detailed report, other countries may prioritize the need for supply in their own countries and under-fulfill contracts in the United States. This risk is particularly the case in China, which manufactures 13 percent of the active pharmaceutical ingredients used to manufacture drugs sold in the United States.

FDA currently uses several tools to prevent, detect, or alleviate shortages. Federal law requires manufacturers of some drugs and medical devices to inform the FDA of potential shortages. (This requirement does not apply to foods, such as infant formula). FDA staff analyzes shortage data and can take several steps. Although FDA cannot normally force a manufacturer to produce more of a drug or device, it can contact manufacturers of drugs and encourage them to do so. It may prioritize and streamline the review of existing marketing applications that would allow other companies to enter the market.

The agency can also allow the import and marketing of a similar version of a drug or device that is approved for sale in another country. Under this latter option, FDA will analyze safety and efficacy data to make sure that the imported product is safe and effective. The agency may extend the expiry dates of products on the market. The FDA may also consider alternatives to compliance actions it would otherwise take. For instance, in the example of the manufacturer of drugs with particulates, rather than recalling the product, FDA may allow the manufacturer to continue to make the product but also require it to provide a filtration system to doctors that would remove the particulates before use. The latter solution is one FDA seeks to avoid but will use in an emergency.

Shortage risks have been exacerbated by the increased prevalence of unreliable suppliers from outside of the United States

Congress, the administration, and FDA have been developing tools to be more proactive in preventing shortages. The CARES Act, which became law in the early stages of the COVID pandemic, required manufacturers of many drugs to develop, maintain, and implement redundancy risk management plans that identify and evaluate supply risks. FDA has the authority to review these plans in facility inspections. A risk factor in a plan might be the aging equipment in our hypothetical example or only having one supplier of the active pharmaceutical ingredient used to make a drug. When evaluating these plans, if FDA believes that a shortage risk is high, it could take steps, like forcing the purchase of new equipment or expediting the review of the marketing application of a competitor.

FDA has implemented an Emerging Technology Program that reduces delays in the agency's approval of new manufacturing technologies. These technologies, including continuous manufacturing, are less likely to result in shortage-causing manufacturing problems, such as particulates generated by the aging equipment in our hypothetical situation. A bipartisan House majority recently passed the National Centers of Excellence in Advanced and Continuous Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Act, which facilitates cooperation between the FDA and manufacturers in developing and deploying new technologies. Retrofitting existing plants or building new ones is not cheap and making these options feasible would likely require Congress to enact financial incentives.

FDA has proposed a system of quality metrics that would help it detect incipient manufacturing difficulties. The present system relies mostly on inspections that catch problems often in an advanced stage. A quality metrics system would require companies to regularly submit data to FDA, such as the percentage of time that a manufacturer had to reject a batch of drugs. The hope is that this data would be a leading indicator of a problem, such as the one in our particulate example. This task, however, has proven to be much easier said than done. FDA has been working on quality metrics since 2013. Challenges include determining which metrics actually are indicators of quality and then normalizing them based on the drug produced. For example, some drugs are more difficult to manufacture than others and would be more likely to generate a bad metrics score. An effective system would have to account for difficulty in manufacturing, including in facilities that make dozens of drugs.

The administration has recognized that a supply chain that is more domestically based—at least for critical drugs—is less likely to experience shortages caused by supply chain disruptions. A more domestic supply chain would also alleviate national security concerns raised by the reliance on drugs or drug components manufactured in China. To that end, the Biden administration has proposed financial incentives to increase domestic manufacturing capacity and to establish federal government procurement guarantees for domestically manufactured drugs.

The discussion over shortages in recent years has focused on medical products. But the ongoing infant formula shortage may cause Congress and FDA to think about new authorities that address potential shortages in life-sustaining food products, such as infant formula and medical foods, specifically used to manage a disease or condition.