The connotations attached to the term "menstruation" are complex and are often rooted in cultures, or they emerge from physiological processes. In some societies, menstruation is completely taboo and people are encouraged to use coded language—words that are used in place of the real words to describe menstruation. A close look at menstruation vernacular across cultures and institutions offers unique insights into how stigma and shame related to menstruation are perpetuated.

In numerous countries around the world, the mere mention of menstruation or any part of the female reproductive system may be frowned upon, even though each day there are around 800 million women, girls, trans-men, and non-binary individuals menstruating. Each of these individuals has different experiences of menstruation—from menarche to menopause–and for many, their menstruation is an ordeal clouded in shame, misinformation, and stigma. Yet, menstruation is a normal, healthy process that happens once a month—except when a woman is pregnant—when the lining of the uterus sheds. Some women and girls are restricted in their daily activities, banned from entering the kitchen to prepare food as it is feared they can contaminate the meal; kept away from religious sites and prevented from praying because of the belief that menstrual blood is dirty and can pollute sacred religious spaces; and even hindered from taking a bath, as it is thought that the water might impede blood flow.

Over the years, efforts have been made to normalize menstruation; however, shame and stigma are still prevalent in many parts of the world. This can be related to a number of factors including cultural norms and beliefs, gender inequality, lack of access to products or safe spaces, as well as limited access to education and sources of information needed to manage menstruation in a healthy, positive way.

Each day, about 800 million women, girls, trans-men, and non-binary individuals experience menstruation

Changes to this paradigm first emerged from low- and middle- income countries, in 2004, when Kenya scrapped the Pink Tax, which placed taxes on menstrual products, disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable women and girls. This momentum continued in 2005, when Chaupadi, a practice that isolates women and girls to huts during their menstruation, was banned by the Supreme Court in Nepal, marking one of the most important milestones in menstrual rights history. Later, high-income countries got involved, with Scotland's Period Products (Free Provision) Act 2021 that brought menstruation and the financial constraints that limit access to period products—sometimes referred to as period poverty—into the political arena through active involvement of several political parties in Scotland.

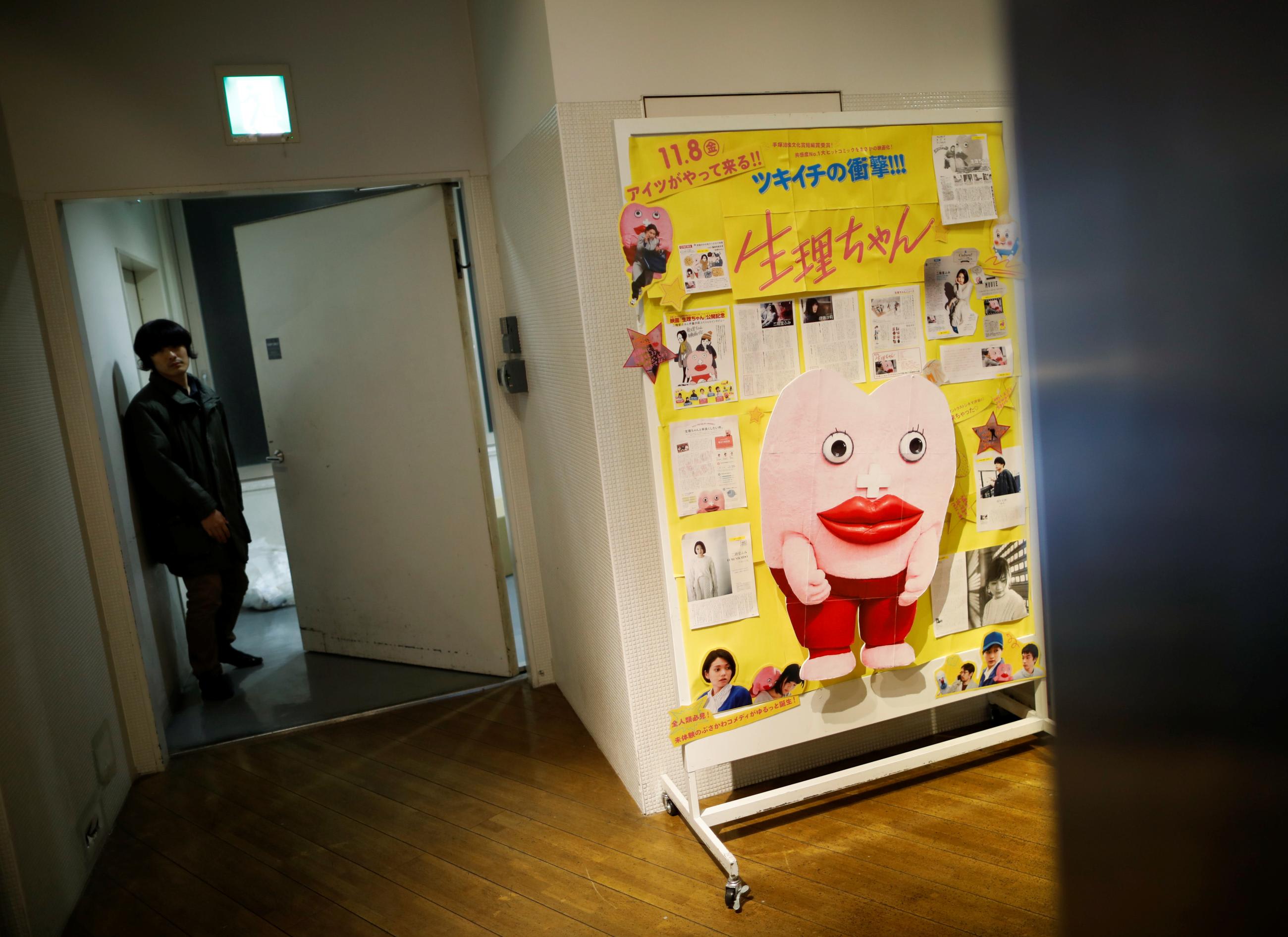

With increasing attention being paid to menstruation, it is important to destigmatize language associated with it as words play an integral part in every human interaction and set the tone for global discussions. The language used to talk about menstruation also reflects how a societies view this topic. Yet, across the world, menstruation is veiled through euphemisms.

The use of euphemisms has allowed people to talk about menstruation without facing discrimination. In Kosovo, the most common expression used is Ato të grave (those women things), while in Kenya, Gukira red sea (crossing the red sea) is used to describe that time of the month, and Hindi speakers in India tend to say Mahina (monthlies). In Germany, it is Erdbeerwoche (strawberry week), Canada and New Zealand use shark week. In Spanish speaking countries, la regla (the rule) is used to talk about menstruation.

Coded language masks the challenges—and the positives—experienced during menstruation and can reinforce stigma. It can even perpetuate misinformation, leading to adverse physical and mental health outcomes.

The use of inaccurate language to address menstruation goes beyond the individual, interpersonal, and community level. Important multilateral institutions, including the World Health Organization and other United Nations entities that are specifically set up to elevate the health and rights of the populations they serve, are framing menstruation as a hygiene issue and using complex technical language. Advocating for the provision of "sanitary" materials and "clean" environments for all women and girls is a fundamental element of most social, developmental and educational programs and policies implemented in low- to middle-income countries by multilateral organizations.

Documents and guides published by these organizations use terms like "sanitary napkins," "menstrual hygiene management," and "menstrual health and hygiene." The focus on menstruation as a matter of hygiene is a relic of historical programs that categorized menstruation as a Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) issue. By framing menstruation as part of WASH and by using overly technical language related to cleanliness in policy and program documents, organizations are perpetuating the idea that menstruation is unclean. This framing also leads to unintended biases during program design and implementation, and represents a failure to view menstruation as a public health, well-being and, above all, a human rights issue.

"A state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in relation to the menstrual cycle"

Misinformation and incorrect language contribute to increased vulnerability among those who menstruate, subjecting them to discrimination, harassment, exclusion, and isolation. This can impact their livelihoods by discouraging school attendance and forcing many adolescents to drop out. It also has profound effects on mental and physical health and even has been shown to lead to suicidal thoughts.

While it's clear that societies still struggle to talk about menstruation, there is hope. In April 2021, a new definition of menstrual health was proposed by the Global Menstrual Collective Terminology Action Group. This organization, comprised of experts from academia, non-governmental organizations, and the United Nations, with representation from high-, low- and middle- income countries, reclassified menstrual health as "a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in relation to the menstrual cycle." Not only does this definition recognize menstruation as a natural bodily function, but it explicitly references the entire menstrual cycle, shining light on the physical, mental, and social aspects that should be taken into consideration when designing educational, developmental, and wellness programs that tackle menstruation at every level. These elements are crucial in the development of these programs and the wider conversation, as menstruation does not occur in a vacuum, but is a shared experience, charged with cultural meaning.

Anyone can experience poor menstrual health, but it disproportionately impacts vulnerable women and girls. We invite policymakers, health-care workers and everyone in between to embrace the official definition for menstrual health and to move away from shame-inducing words and the range of euphemisms that exist. As the number of programs dedicated to menstruation grows, it is vital that we use a shared language to understand that menstrual health is not just about providing products, it's about creating safe environments, too. Normalizing all elements of the menstrual cycle and ensuring that the voice of every community is heard and included in the implementation of programs is necessary to empower women and girls wanting to make informed choices about their menstruation.

The first step on the road to menstrual equity is to talk about menstruation, so let us unite behind the shared term of "menstrual health".

AUTHOR'S NOTE: We recognize that not all women and girls menstruate and not all individuals who menstruate are women and girls, however data suggests that the majority of the 800 million individuals who are menstruating daily around the world are women and girls. For this reason, and for the purpose of this article, we refer to women and girls.