It all started in July 2018. I noticed that my sternum—the bone located in the center of my chest—was bulging, and it hurt a little, too, when I pressed on it. I had it scanned and it turned out to be the beginning of a long series of events.

The CT scan revealed two masses on the lymph nodes in my anterior mediastinum—the area in the front part of my chest between my lungs. There was no question that if it was cancer, it needed to be treated. I needed to have a biopsy before I underwent an operation under general anesthesia. The biopsy was inconclusive, though, and four months later, I had another biopsy done. This time, the sample was sent to the Institut Pasteur de Dakar, a biomedical research center in Dakar, Senegal—over an hour away from my home. In January 2019, I received the results: it was Hodgkin's lymphoma. It is a cancer of the lymphatic system, part of the immune system.

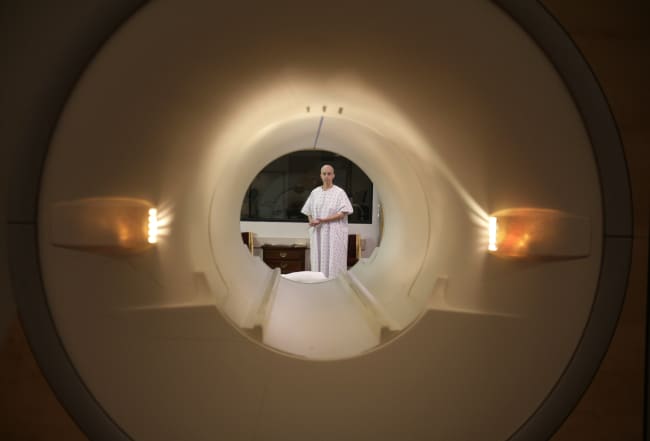

A month later, after undergoing a detailed "pre-therapeutic" assessment, I began chemotherapy treatment. I followed three chemotherapy protocols, and for each, I would get a blood test followed by an abdominopelvic thoracic scan when chemo was complete, to track the chemo's effectiveness.

Cancer is a disease that is very expensive; you have to spend a lot on diagnosis, you spend a lot before starting treatment, and finally, you spend a lot during treatment. Here in Senegal, when you go to the hospital, usually you are given the prices of the chemotherapy drugs you'll take, but they do not tell you that the side effects and/or complications of the treatment will also require you to spend money. And then there is the cost of transport each time you go to the hospital. I live in Thiès and everything I needed medically was in Dakar, 44 miles (71 kilometers) away—about an hour and a quarter by car.

The system is not fair—it reveals how vulnerable we are to disease

Earlier, I mentioned protocol—the treatment regime I was to undergo. The first protocol was composed of sixteen chemotherapy sessions and each session cost me about 130,000 francs (about $220). It was every fifteen days and before each session, it was necessary to have a blood test to see if we could continue the treatment. Fortunately, I managed to keep my job. With the side effects and a treatment rhythm of once every fifteen days, it was not easy.

I come from a modest family and with the help of my husband, we had to fight to get by and also received support from our loved ones. I saw a young man die of the same disease because he was not only in Kolda—more than a ten-hour drive to medical care in Dakar—but also because his parents did not have the financial means. He was unable to afford his treatment.

The cost of pathology services at the Institut Pasteur tallied 250,000 francs ($425), the mid-treatment and end assessments cost 160,000 francs ($270) each time. I could estimate my expenses from the beginning at about 8,000,000 francs ($13,600) over the course of two years and around 300,000 francs ($510) a month. Sometimes, I was unable to obtain my medication at the pharmacy and was forced to go to private pharmacies where often the costs are quadrupled or more.

I am a young doctor—I am supposed to be among the middle-income people in my country, Senegal. But I have a lot of financial difficulties in the face of this disease. After three different treatment protocols, today I am off treatment because the medication I need is not available in my country. I have to travel, most likely outside my country, to continue my care. The situation of the pandemic complicates this, as well as the financial resources I'd need, so I am in a labyrinth of stress due to these factors.

The system is not fair—it reveals how vulnerable we are to disease.

Beyond all this, the side effects of treatment weaken me and have disrupted my pace of work and therefore my profitability. It must be said that this disease has a cost in Africa and therefore we must fight to prevent this. We must think about supporting more patients and think of an Africa where universal health coverage is a reality. To all the cancer patients in the world, I ask them to stay positive and fight to the end.

Thinking about health on a global and holistic level, COVID-19 has taught us lessons and continues to challenge us with its evidence. It is therefore urgent for us to continue by promoting all campaigns, policies, and solutions that aim to achieve inclusive health outcomes where no one will be abandoned or left behind to die because of our geographical location on earth, or our gender, or our skin color, or the GDP of our country, or our monthly income. We must think global and we have to keep this promise to do that.

In Africa, the same diagnoses which elsewhere people recover from or have a huge chance of survival, are not survivable

We live in an unequal world and the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated inequality. For a long time in Africa, we have focused on infectious diseases that wreak havoc, but today it must be said that chronic noncommunicable (NCDs) diseases are emerging and kill many people in developing countries—and they are very expensive to care for. We see campaigns and policies talking about NCDs in terms of prevention, but it is about making care available and facilitating access to care and medicines, otherwise the number of preventable deaths will continue to rise.

And so we continue to witness this without being able to do anything about it. In Africa, the same diagnoses which elsewhere people recover from or have a huge chance of survival, are not survivable. Several factors exacerbate this situation: the problem of diagnosis, a patient's financial means, but especially the availability of treatment.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article has been translated from the original in French.