Few people have led as varied or storied careers in global health as Dr. Helene Gayle. She spent nearly two decades with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, then led the AIDS program for the U.S. Agency for International Development, before leaving the public sector to direct the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s initiatives on infectious disease. Shifting from research and policy to service-provision, she then headed the international humanitarian organization CARE for nearly decade. Most recently, after a stint running the Chicago Community Trust, one of the country’s largest community foundations, Dr. Gayle was chosen in 2022 to become president of the Spelman College, one of the premier historically Black colleges in America.

She spoke with Think Global Health about how her identity shaped those choices, and the questions that her field needs to continue to grapple with.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: How did your identity as an African American woman influence your early career choices?

Helene Gayle: Very much, in many ways.

As I was growing up and formulating my ideas about the world, there was a lot going on: the civil rights movement, women’s movement, anti-war movement, anti-colonialism, anti-apartheid, you name it. We were the young radicals who were thinking about all these broad social movements: As the most wealthy and powerful nation, how do we use that power? How do we think about our responsibility to others? How do we think about our responsibility beyond just the walls of America?

And I got very involved and impressed by this notion of Pan-Africanism; that as an African American my birthplace and life experience is grounded in America but I am also tied to the greater Africa and African Diaspora. That was solidified by an early trip that I took right after college to Togo. I volunteered with Crossroads Africa, a summer program which was the predecessor to the Peace Corps. I got treated in a way that really reinforced the sense of connectedness, and the recognition of Africans in America with Africans in Africa. Obviously, a lot of differences, centuries of separation — but it was something that really stayed with me.

Part of the reason that I went into both pediatrics and public health was because I recognized the global nature of both of those fields. Child survival and issues around pediatrics were a very important part in the global health arena. And so, part of my own choices were because I wanted to be able to have a career that allowed me to think not only about issues in America, but Africa, and ultimately, the globe.

As I was growing up and formulating my ideas about the world, there was a lot going on: the civil rights movement, women’s movement, anti-war movement

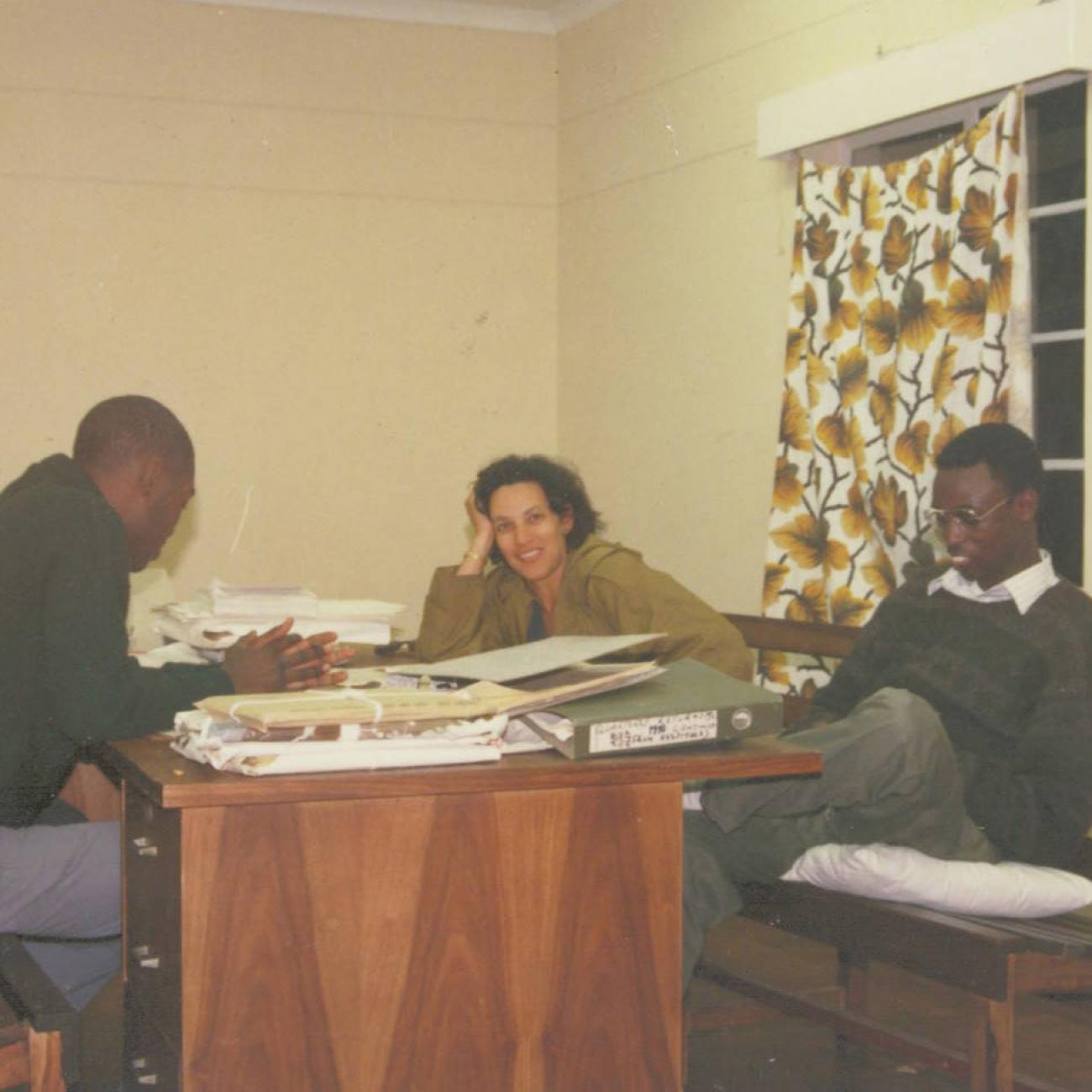

Dr. Helene Gayle

Think Global Health: The history of contributions by African Americans to global health is not as well-known as it should be. Were particular mentors or influences important to you?

Helene Gayle: The first African American that I can remember in global health was a woman named Connie Davis. She spoke at Johns Hopkins when I went there to get my MPH. It struck me because you didn’t see a lot of people of color, particularly African Americans, in global health. And in the global arena in general there’s a lack of diversity.

For African Americans, there is a deep sense of giving back to the proximate community. And coming from the African American community, where the needs are so great and where we still have challenges, that’s what the majority of African Americans are committed to. How can I make a difference in my community?

So it is almost a luxury, if you will, to be able to think about something beyond your direct circumstances, your direct community. But I think now we're seeing much more diversity in global health and global affairs broadly.

Think Global Health: Did you ever feel a tension — I don’t want to say a guilt — but was there ever a tension that you were turning away from things that were right there at home to issues that were abroad?

Helene Gayle: I probably have done equal parts domestic, equal parts global. Because I’ve been able to go back and forth, it’s been a good mix.

There were times when I would come back home and talk to friends and colleagues who were very focused on U.S. issues, and people wondered, “Why are you off with people over there while we’ve got so much [to deal with]?” A lot of the issues that I was focused on were just not what people thought of as critical or as immediate. But having a foot in both worlds has enabled me to feel like I can fulfill some of my commitment to my own community here, as well as thinking about the globe.

Think Global Health: Your background in social movements is interesting because much of your early career was spent at the CDC. Was it a hospitable place for that type of upbringing and thinking?

Helene Gayle: By and large, people who work in public health are motivated by the social mission. Public health is all about equity. I came to the CDC for the two-year epidemiology training program and stayed for twenty years, and I think it’s largely because I felt I had found my people: people who were like-minded, who wanted to create change, who saw the need to think about equity and social justice as integral to what we did in public health. And so I felt very much like I was with kindred spirits. People don’t necessarily think about CDC as a hotbed of social progress but in fact, that’s why a lot of people are there to begin with.

Think Global Health: There is an ongoing debate over the development aid model. Did being an African American inform your views about how that relationship works or could be better?

Helene Gayle: Whether it’s because I’m an African American or just because of my experiences, it was much more comfortable for me, or obvious, that we should be listening to people. And that we should not be coming in with answers.

Partly because I saw that in my own communities in the United States, people come with their ivory tower programs that fail over and over again because they don’t talk to people.

And because in my own life I have been subjected to people presuming that they had the answers, or that I didn’t have anything to contribute. I had a sensitivity to that.

But I also I give public health a lot of credit for being ahead of the curve in terms of listening to community and community engagement, and some of those things that I think weren’t necessarily as natural in some of the other development spaces.

The other part is that working as an African American in Africa, and globally, I think I am viewed somewhat differently. I hear things that others might not hear. While I feel like my white colleagues who worked in global health were treated very much like friends and people valued them, I think I was treated more like family. There was a difference in terms of how people related to me that gave me different insights, perhaps.

Sometimes it took time for people to appreciate, recognize, acknowledge that I might be the leader of the team, or the person with the most knowledge

Dr. Helene Gayle

Think Global Health: Were there disadvantages for you as well? And how did you handle that?

Helene Gayle: I think in some settings, it might have been gender as much as race. Often times I was the woman leading a team in countries where people were not used to seeing women.

There were a few times where being African American—maybe not so much in Africa, but in other countries—where people had a lot of misperceptions about Black people in America because TV shows mainly show bad stuff. Sometimes it took time for people to appreciate, recognize, acknowledge that I might be the leader of the team, or the person who had the most knowledge about things. I don’t know whether it was gender or race, or often I was the youngest person. For the most part, I felt that if I was able to demonstrate my expertise, that I did get the respect that I deserved.

Think Global Health: What do you see as the most important things that Global Health needs to be introspective about in order to continue to improve?

Helene Gayle: This has nothing to do with race or whatever, but I think setting higher standards and higher goals. You’ve got to make change incrementally, but being very clear about what change do we want to see.

Many remember when a senior U.S. government official said that Africans can’t adhere to antiretrovirals because they don't have watches. I get what he meant. I don’t think it was poorly intended. But it didn’t communicate the sense of the possible.

It’s the same debate that I think goes on around whether vaccine manufacturing should be in the countries where vaccines are needed the most. All sorts of concerns about capacity and whether that’s feasible. “Isn’t the model better for us to just keep making vaccines because we know how to do it well and then ship them?” We all know that there are huge gaps — but if we never think that the goal is to make sure that Africans can manufacture their own vaccines, we won’t get there.

So I think we keep imposing limits, and not really focusing on what’s the possible. If we honestly believe that those populations deserve it and that they have the capacity to do it, we’d work in a different way.

Think Global Health: I’ve always been told that being a university president is the best job in America. What drew you to this role running one of the leading Black institutions in the country?

Helene Gayle: I was minding my business, loving my job in Chicago, thinking this was absolutely the last full-time job I would ever have in life, as I see all of my same-age friends retiring and spending lots of time on beaches. I’d made a lot of changes in Chicago. I had done the hard work that needed to be done in that first five years that I was there. And I knew I had lots of great people to continue the work.

So when I was asked to consider Spelman, I asked myself, if I still had remaining energy, what would be the most wonderful thing I could contribute to? And I felt that the [answer was] to contribute to the next generation of young women who looked like me.

Spelman’s model is “Making a choice to change the world.” So, to me, it was inspiring to think about how could I have a role in continuing to elevate this outstanding institution, that is known for producing some of the most incredible Black women leaders, at a time where I think the need is greater than ever. And the interest is greater than ever: Spelman had a tripling in applicants in the last decade where other liberal arts colleges are having a hard time finding students.

Frankly, I have spent all of my career helping to perfect majority institutions — majority institutions who I feel share my values — but to be able to have the opportunity to contribute to a Black institution that is all the things that Spelman is, I felt was something worth putting off my beach time for.

Think Global Health: Your students doubtless seek many different careers but for those seeking a role in global health, do you have any thoughts or advice?

Helene Gayle: Global health is a career that so many young women are interested in. And Spelman is the highest producer of young Black women who go on to get PhDs in the STEM area. Health sciences and medical careers are always one of the top places that young women want to go and pursue careers. And global health, of course, is getting more and more popular on every campus.

I give [my students] the same advice that I give most young people these days: stop being so focused on thinking there’s one right way. Figure out what your way is and do it. I was just with a group of young women, STEM majors, and of course, the questions always are, “Does it matter to get an MPH? Do I need to go to medical school?” My answer is always to do it in the way that makes the most sense for you, that is financially feasible, that speaks to your passion.

I think I’m a great example of how you start your career one way, and you never know where it will end up. I never would have thought that I would start my career in pediatrics and end my career as a college president. But here I am.