Much has been said about humanity's need to address our changing climate and yet a collective effort to shift this reality still struggles to gain traction. With so much at stake, it is imperative that countries, industries, and even individuals do their part in the hope that the sum of our collective efforts can move the needle toward reducing the rate at which our atmosphere warms.

While many immediately think of industries such as agriculture, manufacturing, energy production, and transportation as the major producers of greenhouse gasses (GHG), health-care systems should have a place in this discussion. The United States health-care system and the United Kingdom's National Health Service have been shown to contribute as much as 8.5 percent and 7 percent, respectively, to their nation's total GHG emissions.

Hospitals and Green House Gas Emissions

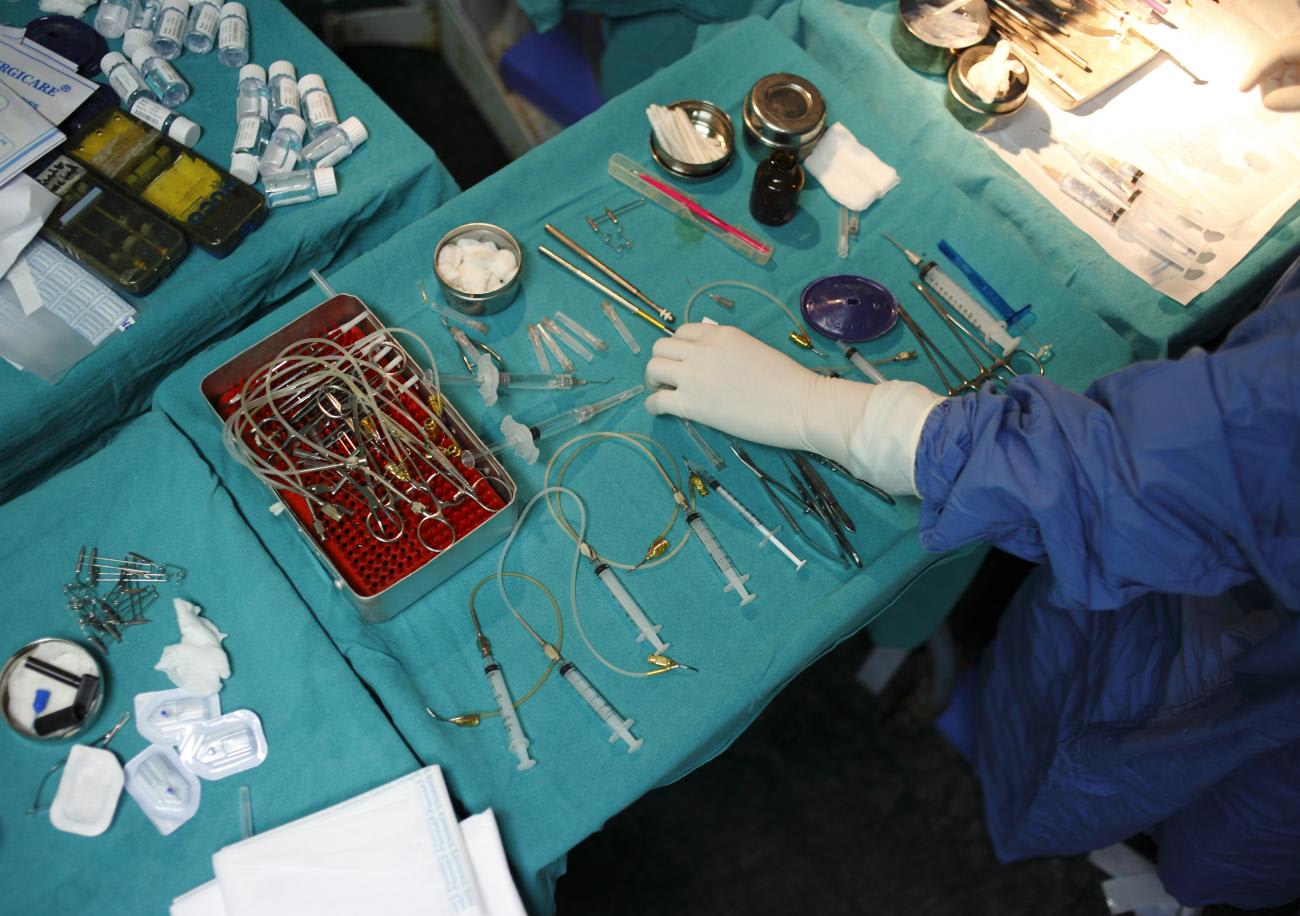

Hospitals play a major part in GHG emissions, but one space contributes more significantly than any other: the operating room. A review of the emissions from hospitals in three countries showed that a hospital's operating rooms can demand six times the energy compared to the entire rest of the hospital. The researchers estimated the total carbon footprint of all operating rooms in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom to be 9.7 million tons per year, or the equivalent of nearly two million cars. For comparison, Ireland operated roughly 2.1 million vehicles in 2018. Desflurane, a volatile agent used as an inhalational general anesthetic for surgery, has been shown to have 2,540 times the heat-trapping ability of carbon dioxide (CO2). With just one hour of use, Desflurane could contribute the same amount of emissions as a single car that traveled up to 130 miles.

The total carbon footprint of all operating rooms in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom is estimated to be 9.7 million tons per year

If we are going to tackle this issue properly, health-care systems need to understand how the entire surgical system impacts our environment. For example, one study found that 62 percent of GHG emissions from health care came from the supply chain while just 24 percent came from direct care delivery.

Some forward thinkers have even devised a matrix that highlights areas to mitigate the impact on climate change from the prehospital setting, during the hospital admission, and through the post-discharge course.

How Climate Change Hurts Health

While health-care systems contribute to climate change, at the same time they bear the fallout of the health effects of climate.

The effects on health due to climate change are vastly understudied, and as a result, are probably more impactful and detrimental than we think. Congenital cataracts and neurologic disabilities, for example, have been linked with rising temperatures. As temperatures rise, it is likely that surgical complications, such as surgical site infections, will increase. Increasing temperatures globally have also been shown to influence pregnancy complications and worsen cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions, jeopardizing the health of patients who need surgery.

Climate events such as wildfires, floods, and storms not only have the potential to directly cause harm to people, they threaten the very infrastructure needed to treat those who are harmed. Critical infrastructure that supplies water and electricity and even the roads necessary to access hospitals are at risk of damage if they are not "climate-proofed."

Climate change threatens all communities across the globe, but not all countries are equal contributors to the problem. Since the Industrial Revolution, the United States has been responsible for 40 percent of excess CO2 emissions, and high-income countries (HICs) are responsible for 92 percent. Yet, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are often left to deal with the consequences and lack the means to prepare for, or recover from, climate events.

This reality has fueled calls for greater financial support from HICs. Some nations have responded with pledges of up to $100 billion dollars per year. Quite a sizable sum, but only a piece of the estimated $571 billion in damages related to climate change experienced every year by the global south. This figure does not include the amount necessary to protect vital infrastructure or integrate technological advances. Compounding this problem, HIC follow-through on such commitments is still lacking. Whatever we do, we must find ways to break the cycle and balance the scales together.

A Road Map for Global Surgery Teams

As advocates for global surgery, our focus is on ensuring safe, affordable, and timely access to surgical care to the 5.3 billion people who currently do not have access. This entails an unprecedented scale-up of 143 million more operations every year. But as we learn more about how health-care systems, particularly operating rooms, contribute to climate change and how climate change influences health, we must stop and consider the potential secondary harms of our efforts. We cannot allow attempts to achieve universal surgical access threaten the lives of every person on this planet and all the lives in the generations to come.

We cannot allow attempts to achieve universal surgical access threaten the lives of this generation and those to come

The Global Road Map for Health Care Decarbonization outlines seven high-impact actions to balance these goals. From health care powered by renewable energy sources to minimizing the emissions of patients and staff as they travel, there are effective means to reduce the growing carbon footprint of health-care systems globally.

We can reduce overall energy use through occupation-based energy consumption for operating rooms. The heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems in operating rooms can be responsible for as much as 99 percent of operating room energy demands. By scaling down HVAC usage across a majority of operating rooms during the quieter night time hours and on weekends, hospitals could see up to a 50 percent reduction in energy consumption and costs.

Additional strategies include minimizing single-use plastic, looking for ways to make more items reusable, shifting to LED lighting, and minimizing hazardous waste. It is significantly more energy and cost intensive to dispose of hazardous waste when compared with regular hospital waste. If hospitals improve efforts to appropriately assign hazardous waste the resultant cost and environmental impacts can be huge. In total, hazardous medical waste is roughly 25 percent of medical waste but accounts for 86 percent of the cost. Up to 90 percent of hazardous waste has been inappropriately classified resulting in staggering inefficiencies.

Some have argued that public health programs aimed at directly reducing the burden of surgical disease could have the added benefit of reducing the impact on climate change. Potential work aimed at lowering the wider burden of surgical disease could add a new dimension to the "reduce" portion of the beloved mantra "reduce, reuse, recycle."

Today the world faces an immense need for surgical scale-up across LMICs. At the same time, we are living in an era where green technology is increasingly cost-effective and renewable energy sources are often price-competitive with fossil fuels. Due to this unique confluence, LMICs have the opportunity to revolutionize "green" health-care delivery. Instead of retrofitting existing buildings, organizations, and governments in LMICs that are working to scale up their health-care systems, LMICs have the chance to build green infrastructure from the ground up.

We must look for ways to shift energy sources from fossil fuels to renewable and cleaner sources of energy such as solar, wind, or hydroelectric power. We must reimagine how health-care supply chains can be built to minimize any unnecessary emissions. We should rethink health-care infrastructure to allow for simultaneous climate-friendly and climate-resilient designs. Rather than recreating the highly emitting and polluting surgical infrastructure of HICs, there is an opportunity to shift the paradigm as LMICs become leaders in quality, affordable, timely, and green surgical care.

LMICs have the chance to build green infrastructure from the ground up

Hospitals in high-income countries are also starting to use their wealth to implement green technologies. Existing academic partnerships between HICs and LMICs is an avenue through which these advances should be shared. The World Health Organization Sustainable Development Goals, commitments such as the Paris Climate Accord, and climate focused policy frameworks offer insight and practical steps toward building surgical capacity that is environmentally sustainable.

HIC actors need to invest in LMIC providers by supporting their proclivity toward ingenuity and working together to create climate-friendly surgical care solutions.

Policies and technologies that reduce GHG emissions from operating rooms will allow us to improve the health of our planet while simultaneously improving access to surgical care for those who currently lack it. The judicious integration of climate-consciousness with surgical care will extend our mission of healing beyond the operating room and those alive today. It will help to ensure the preservation of this remarkable planet for generations to come.

AUTHORS' NOTE: This work is a combined effort of the Climate in Obstetrics, Anesthesia, and Surgery Team (COAST), a research collaborative between the Program in Global Surgery and Social Change at Harvard Medical School and the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women's Hospital.