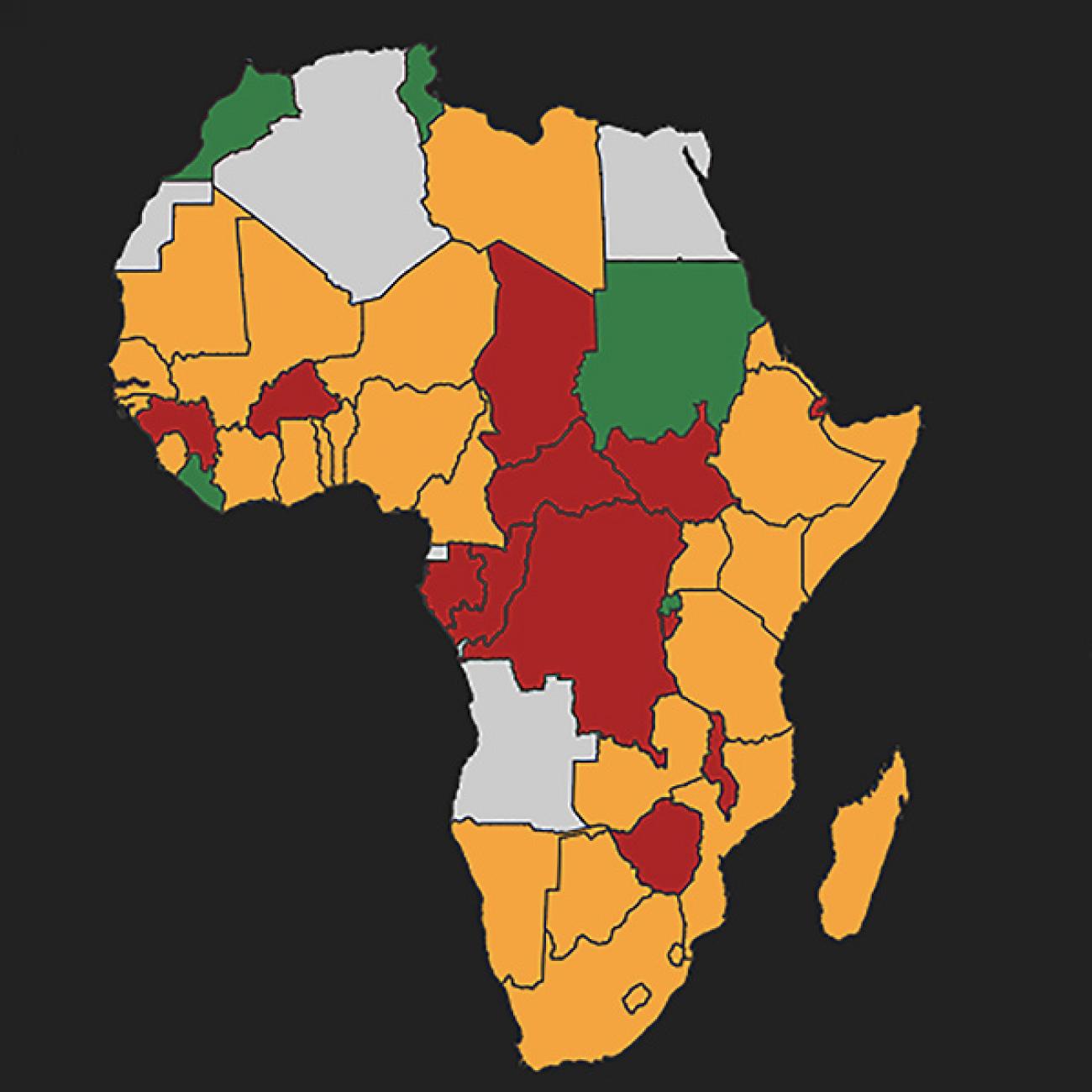

The coronavirus pandemic has started to hit developing countries, and all forty-seven countries of the World Health Organization (WHO) African Region are now affected, with the cumulative number of cases in Africa exceeding 784,800 as of July 30, 2020. The landscape of the battle against COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries is different from that of high-income countries. Due to the lack of adequate health systems, the same approaches could have unintended consequences making them less effective in these countries.

The reduction in the coverage of maternal health-care service of 45 percent would result in 56,700 maternal deaths

In developed countries, the battle against COVID-19 has essentially become a virus-centric or so-called “vertical” approach, with a primary focus on enhancing capacity for testing and treatment. But such virus-centric approaches will be problematic in developing countries because they will require resource reallocation from other projects that are themselves designed to cover unmet medical needs in these countries. One modeling study highlights that the reduction in the coverage of maternal health-care service of 45 percent would result in 56,700 maternal deaths. Another study estimates that in the worst scenario, the annual mortality due to malaria in sub-Saharan Africa this year could be twice as high as the number of deaths in 2018, should the intense resource reallocation occur.

Second, these unintended consequences could undermine the credibility of external medical assistance. One of the biggest lessons we learned from the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa was that control of communicable diseases requires the acceptance and understanding of the local people.

It showed how preparedness and response activities should be synergized with a long-term development agenda. Emergency responses to emerging infections should not only focus on safeguarding and distributing technical solutions to contain the outbreak—they should be human-centric, aiming to enhance the local people’s acceptance and understanding of Ebola projects. The way to do this is by carefully considering the wide range of the needs of the local community.

The Convergence and Divergence of Health Security and Development Agendas

The difficulty in applying a simple virus-centric approach is why the battle against COVID-19 is a more Herculean task in developing countries. Given the lack of adequate health systems, how do we simultaneously pursue the goal of containing outbreaks while also strengthening health systems in developing countries under significant resource constraints? Pursuing such a human-centric approach first requires an understanding of the commonalities and differences between the health security and development agenda. A simultaneous pursuit of these two goals is difficult because they are fundamentally different in their purposes and approaches. But there should also be commonalities between the two agenda: We can leverage them to craft an effective resource allocation strategy during the pandemic.

Why the battle against COVID-19 is a more Herculean task in developing countries

The reduction of health, economic, and political risks is the key conceptual similarity between the health security and development agenda. Some have argued that pursuing the global health security agenda and promoting universal health coverage, both example of “horizontal” approaches, are similar in that they aim to reduce the health, economic, and political risks of the local people. The security agenda focuses on reducing the risk of infection, while the universal health coverage focuses on securing the access to routine and emergency medicine broadly, including reducing the risk of other diseases and ameliorating their economic consequences. The same conceptual convergence can be observed in global health security and the sustainable development goals, as evidenced by the fact that the United Nation’s 2030 agenda emphasized the importance of freedom from poverty, hunger, disease, want, fear, and violence.

On the other hand, pursuing health security and the sustainable development goals diverge in conceptual and practical ways. First, while the health security agenda’s main focus is on the short term—protecting people from the immediate risks of an emerging infection or some other health crisis—the development agenda aims to achieve long-term health goals by empowering local people with access to care and good health information. Second, global health security is focused on the containment of a pandemic at a global level, across borders, but sustainable development projects could be more narrowly zeroed in on the needs of the local communities.

Freedom from poverty, hunger, disease, want, fear, and violence

That's the crux of the problem. In a global health crisis, with limited available resources, the re-allocation of resources from long-term development programs to crisis responses is the easiest expedient. Since the majority of funding for long-term programs comes from developed countries or agencies within developed countries anyway, those resources could be redirected from development projects to health security ones. Who would argue with the wisdom of prioritizing protecting human lives in the immediate health crisis over spending on more long-term programs?

I, for one, would.

Particularly in developing countries, health security and achieving sustainable development goals are the two wheels of a cart even during the pandemic: take off either wheel, and you will be left dragging a box. An effective containment requires both protection and empowerment of the local people—both short-term emergency responses as well as long-term spending on improving health systems.

Take off either wheel, and you will be left dragging a box

Given the broad scope of the sustainable development goals and the ongoing resource constraints, an effective prioritization of limited financial, human, and health resources should be permitted during the pandemic, but not in a zero sum way. The key to effective prioritization is to focus on the convergence of health security and development agenda, and to invest in the projects that contribute to the reduction of health, economic, and political risks of the local people. Even during the pandemic and under significant resource constraints, we must not stop investing in the development agenda, as the long-term investment to meet the local needs is the key to effective containment operations.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author acknowledges Joy Li for her thoughtful comments on the earlier version of this article—as well as the Future of Diplomacy Project at Harvard Kennedy School and the Ito Foundation for International Education Exchange. All views expressed in this article belong solely to the author and do not represent the opinions of the author’s affiliations.