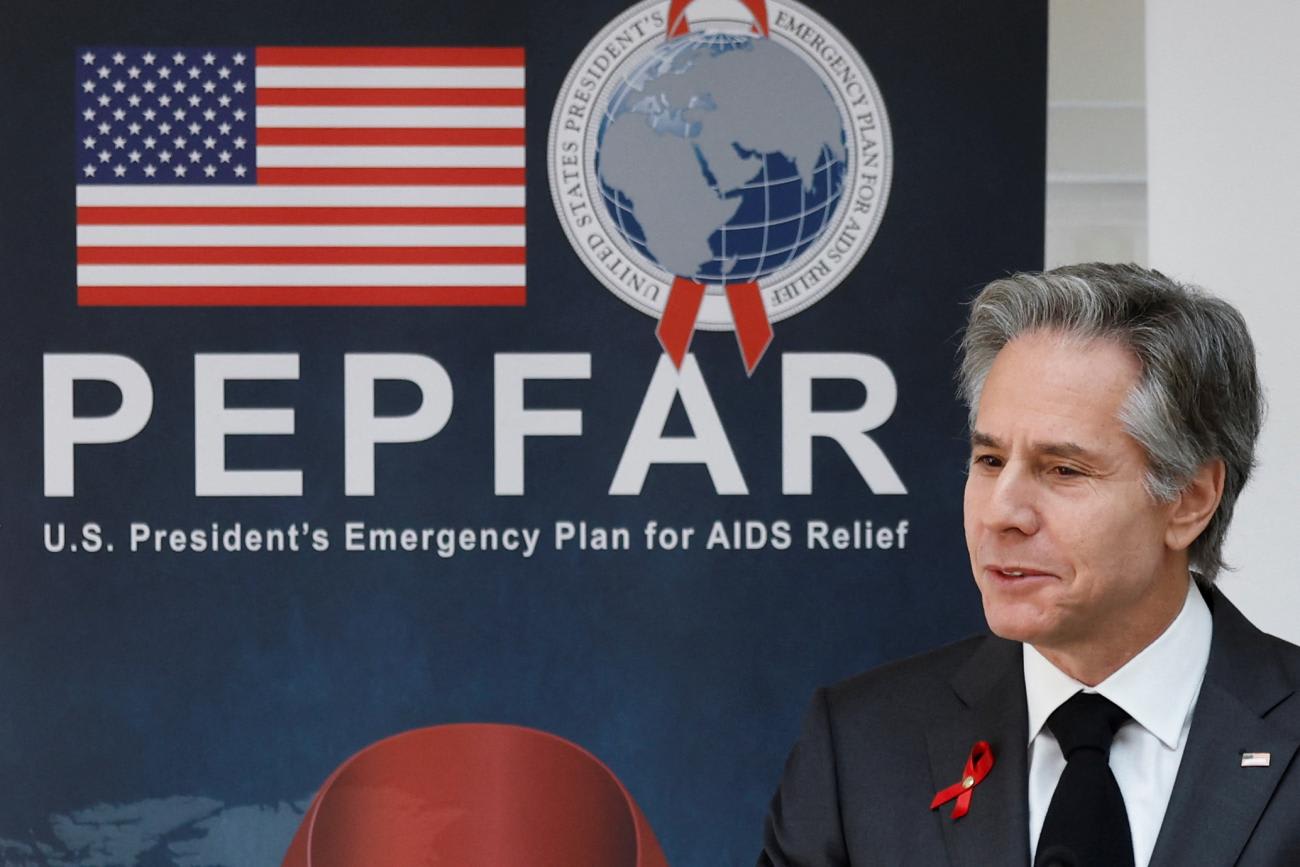

Republican lawmakers have proposed prohibiting dispersing foreign aid, including funds for the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), to organizations that provide or promote abortion services using any funding source. Several Republican presidential candidates have vowed to launch military attacks on foreign drug cartels to stem the flow of illicit fentanyl into the United States.

The anti-abortion proposal and the promises to use military power to mitigate a domestic health crisis have raised policy concerns. They also echo concepts from counterterrorism policy after September 11, 2001. In the wake of that tragic day, the United States asserted that it had the right under international law to use force against terrorist groups within countries unable or unwilling to counter the threats such groups posed. That approach informs the interest in military strikes against cartels.

Will implementation of those countermeasures be constructive or damage the power and influence of the United States?

After 9/11, the U.S. government applied the prohibition against providing material support to terrorists expansively. The proposal to prevent U.S. foreign aid from indirectly facilitating abortion expands the prohibition on direct funding of abortion services to ensure that such aid does not support abortion in any way.

Parallels between post-9/11 counterterrorism strategies and the anti-abortion and military-attack proposals offer one way to analyze those ideas. Both proposals identify transnational threats to life and health within and beyond the United States that call for extraordinary countermeasures against nongovernmental actors.

The proposed policy escalations concerning the fentanyl crisis and abortion raise questions much like those the war on terrorism generated. Are extraordinary countermeasures justified? Will implementation of those countermeasures be constructive or damage the power and influence of the United States?

Fentanyl and the Use of Force

Illicit fentanyl use is a U.S. public health crisis. The crisis resembles previous addiction tragedies despite the United States' waging a war on drugs and combating transnational organized crime, including drug cartels. The scale and impact of fentanyl abuse have overwhelmed years of domestic and foreign policy efforts to reduce demand for, and curtail the supply of, illicit drugs in the United States.

Such comprehensive policy failure ignites interest in new approaches, as happened with counterterrorism after 9/11. In foreign policy, traditional strategies to stem the supply of illicit fentanyl into the United States encounter problems. Neither the Donald Trump nor the Joe Biden administrations succeeded in getting China to stop exporting precursor chemicals that cartels use to manufacture fentanyl. Cooperation with the governments of Mexico and other countries has proved difficult because, in part, they lack the political, economic, and law enforcement capabilities to put the cartels out of business.

After 9/11, the U.S. government acted unilaterally—including through military force—when other countries were unwilling or unable to confront terrorist threats to the United States. With fentanyl, the Biden administration has indicted Chinese nationals for drug smuggling. Concerning fentanyl trafficking, Republican politicians have repurposed the post-9/11 claim that the United States has the right to use force against terrorists to justify attacking cartels when other countries are unwilling or unable to address the trafficking threat to the United States.

Material Support for Abortion

Post–Cold War concerns about terrorism led to laws prohibiting material support for foreign terrorist groups. After 9/11, the prohibition was expanded. In Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (2010), the Supreme Court held that the material-support law banned nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) from teaching international humanitarian law—which prohibits acts of terrorism—to members of foreign terrorist groups.

Using force against cartels would reinforce perceptions that U.S. rhetoric about a rules-based international order is meaningless.

The Supreme Court ruled that the statute banned "any contribution," including teaching international humanitarian law because such an act "frees up other resources . . . that may be put to violent ends." The court concluded that criminalizing such indirect support for terrorists did not violate the First Amendment rights of freedom of speech and association. Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project highlighted how far the U.S. government was willing to go to defeat terrorism.

Similarly, Republican lawmakers and pro-life advocates want to prohibit dispersing foreign aid to NGOs that provide or promote abortions with non–U.S. government funding. The objective is expansive—to prevent foreign aid from supporting, even indirectly, the "global abortion industry." Proponents want the United States to go to greater lengths and end any contribution that foreign aid might make to abortion.

Karl Hofmann, leader of an NGO opposed to the proposed prohibition, described the strategy as an attempt to force NGOs implementing U.S. foreign aid programs, including PEPFAR, to "cease any other work they do providing safe abortions" and from "doing what is legal with other people's money." Hofmann argued that the prohibition would "muzzle" U.S.-based NGOs in violation of their constitutional rights, such as the freedoms of speech and association protected by the First Amendment.

Fit for Purpose?

The parallels between post-9/11 counterterrorism policies and ideas for the fentanyl crisis and the foreign aid–abortion nexus are interesting but should not be pushed too far. Republican and Democratic administrations supported those counterterrorism measures, but no such agreement exists on attacking cartels to stem fentanyl trafficking or eliminating indirect connections between foreign aid and abortion.

That lack of consensus undermines the legitimacy of both ideas. Allies and adversaries could perceive both strategies as the projection of America's toxic politics and more evidence of dysfunctional U.S. policymaking. The willingness to compromise reauthorization of PEPFAR—a lifesaving program long sustained by bipartisanship—unless all foreign aid implements a controversial anti-abortion agenda underscores how divisive domestic politics have become in defining national interests to guide foreign policy.

Attacking cartels faces other legitimacy problems. The just war tradition holds that the use of force must be a last resort, be undertaken to restore peace, and have a reasonable chance of succeeding.

In a strategy for a Republican administration taking office in January 2025, conservatives recommended actions to counter the fentanyl crisis, including preventing drug abuse, treating addiction, supporting recovery, reducing illicit drug access, disrupting the flow of such drugs across U.S. borders, and cooperating with other countries. The availability of those measures makes it clear that military strikes would not be a last-resort action intended to restore peace. As happened with U.S. military attacks on terrorists and insurgents in Afghanistan and Iraq, cartels would respond violently, raising questions about what success means in a context of escalating violence.

Using force against cartels would reinforce perceptions that U.S. rhetoric about a rules-based international order is meaningless

Tell Me How This Ends

Criticisms of U.S. counterterrorism have highlighted how the war on terrorism damaged the United States globally. Evaluating promises to attack cartels and subject foreign aid to an anti-abortion agenda includes thinking about the consequences for U.S. power and influence.

Military operations against cartels would create geopolitical blowback. Such operations, and the cycles of violence they would unleash, would make Mexico and other countries more willing to work with China, embrace nonalignment, and suspend cooperation with the United States on migration, drug trafficking, and other issues. Using force against cartels would reinforce perceptions that U.S. rhetoric about a rules-based international order is meaningless.

Concerning foreign aid, the United States is attempting to counter China's global development efforts. Developing countries' growing interest in nonalignment puts U.S. foreign assistance under more competitive pressure. The controversy over foreign aid and abortion could damage the United States geopolitically if it prevents Congress from appropriating meaningful aid.

If the controversy does not derail appropriations, applying anti-abortion conditions (such as through an executive order) could curtail the effectiveness and efficiency of foreign aid by limiting the quantity or quality of implementing organizations and increasing compliance costs. Developing countries often chafe at conditions attached to U.S. aid, particularly relative to Chinese assistance. Imposing anti-abortion conditions could make that problem worse as the United States competes with China in the development sphere.

Elections Have Consequences

Whether promises to launch attacks against cartels and proposals to impose anti-abortion principles on foreign aid become U.S. policy depends on the outcomes of the 2024 elections. With campaigns under way, pre-election prospects for bipartisan approaches to the fentanyl crisis and the relationship between foreign aid and abortion are not good. As a result, the United States will continue to fail to manage health crises and challenges at home and abroad.