The Pandemic Recovery Survey, which gathered responses from more than half a million participants across twenty-one countries, has brought to light a stark reality: 31 percent of students are falling behind in math and 26 percent are in reading. The impact is more severe among students from food-insecure households, a reality that mirrors the broader economic disparities magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

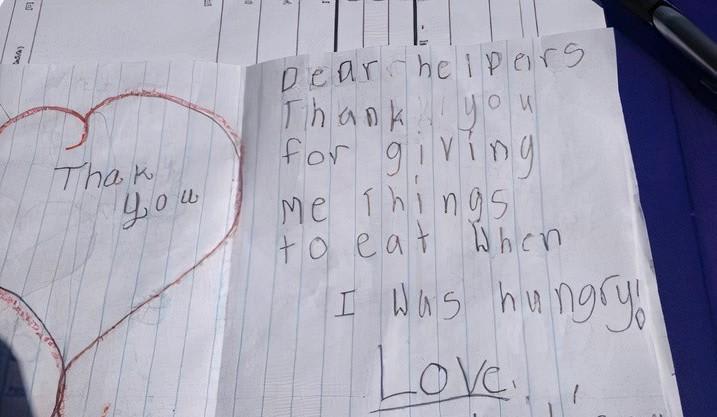

The findings from this survey, released last autumn, underscore the heightened relationship between food security and educational outcomes. Given the educational upheavals related to the pandemic, the role of nutrition in children's academic journeys is more evident than ever. Essential programs like the free summer meals that bridge the gap for those awaiting the resumption of school meals in the fall highlight the ongoing need for support as societies strive to recover from the pandemic.

A Snapshot from Twenty-One Countries

In Latin America, the correlation between food security and educational outcomes is particularly pronounced. Chile, often seen as a regional leader in educational attainment and equality, has a lower proportion of students reporting decreases in math skills than its peers do.

31 percent of students are falling behind in math and 26 percent are in reading

When examining the Pandemic Recovery Survey data through the lens of food security, however, it's evident that even in Chile students from food-insecure households now face greater challenges in maintaining their academic levels.

The countries in Southeast Asia reflect a similar trend, food security playing a critical role in academic achievement since the pandemic. In Vietnam, a significant number of students from food-insecure households report lower than anticipated math and reading skills, underscoring the need for comprehensive support systems that address both educational and nutritional needs.

Food Insecure Students Experience Learning Disparities

Survey respondents who experienced food insecurity reported lower math and reading skills across countries

More than half of food-insecure students in India demonstrated lower than anticipated math and reading skills than 38 percent of their food-secure peers. This finding adds to other concerning trends showing that COVID-19's impact on schooling in India disproportionately affected girls, especially when compounded with other socioeconomic characteristics.

In three African countries, the effect of food security on education is stark—about half of all Pandemic Recovery Survey respondents from South Africa, Egypt, and Nigeria reported sometimes or often not having enough to eat. The survey data indicates a substantial gap in learning outcomes between students from food-secure and food-insecure households.

In Turkey, the educational disruption caused by COVID-19 affected nearly nineteen million children, including more than 760,000 refugees, and more than one million teachers. Students from impoverished households and refugees from Syria were especially hard hit, often lacking access to digital resources essential for educational continuity during school closures. This is reflected in the Pandemic Recovery Survey data, which shows that 50 percent of students in math and 46 percent in reading reported skills below expected levels.

In the United Kingdom, considered a leader in education systems, the transition to distance learning during the pandemic exacerbated educational inequalities, particularly among at-risk groups. One study found that students from historically disadvantaged backgrounds—including those receiving free school meals—spent up to 30 percent less time on school work and learning at home than more advantaged students. Although free meal programs aim to alleviate some disparities, they do not fully mitigate the broader socioeconomic factors that contribute to learning loss.

Students Face High Rates of Food Insecurity

In some countries, over half of respondents reported "sometimes or often not" having enough food to eat

The Pandemic Recovery Survey's revelations toward learning loss are echoed in the December release of the 2022 Program for International Student Assessment, which uncovered a concerning global decline in math proficiency—with students' scores dropping to the lowest point in the test's two-decade history. More than a third of fifteen-year-olds are now struggling with basic mathematical concepts, and these trends come despite an increase in the proportion of students earning high school diplomas in the United States and globally.

Children are graduating without knowing core concepts, and even though this backslide is not a new phenomenon, the pattern's acceleration over the past two decades has been intensified by the pandemic. The causes are multifaceted, with unequal access to technology, socioeconomic factors, and inconsistent school support all contributing to the issue.

But the Pandemic Recovery Survey's findings on the relationship between food security and learning demonstrate a clear pattern: students from food-secure households report higher rates of higher than anticipated math and reading scores than those from food-insecure homes, even when controlling for household finances.

Students Experience Lag in Math and Reading Skills

High rates of students across 21 countries are experiencing lower than anticipated math and reading skills

Beyond Nutrition: Policy Implications and Initiatives

The Pandemic Recovery Survey highlights the connection between food security and educational outcomes, but addressing nutritional needs is not a panacea for the broader challenges within education systems. To close the learning gaps exacerbated by the pandemic, policymakers need to adopt a comprehensive strategy that goes beyond food security and addresses other social and economic sources of inequality.

In the United States, the evidence on learning loss paints a grim picture of the pandemic's long-term impact on education. School closures have set student progress in math and reading back by two decades and exacerbated the achievement gap between poor and wealthy students. In 2023, not a single student across thirteen high schools in Baltimore, Maryland, scored proficient on the state math exam. The persistent lack of proficiency points to systemic educational challenges that extend beyond financial resources or nutritional support.

The Pandemic Recovery Survey has some limitations given that its scope involved only students who remained enrolled during the pandemic and ostensibly came from wealthier families than students who dropped out. Its figures likely underestimate the true extent of the pandemic's impact on education and learning.

For example in India, dropout rates more than tripled during the pandemic, disproportionately affecting students from disadvantaged backgrounds. That surge suggests the children and adolescents who are most at risk of educational setbacks are underrepresented in the data, which is skewed toward students who are more likely to have remained in school.

The evidence on learning loss paints a grim picture of the pandemic's long-term impact on education

Policy recommendations should include the integration of nutritional support within academic programs and a critical examination of existing educational practices and infrastructure. Initiatives such as São Paulo's school meal program showcase proactive responses to this challenge. Investment in digital infrastructure is also necessary to ensure equitable access to online learning resources that can level the playing field for students from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. In the United States, federal funds aimed at addressing learning setbacks are set to expire in 2024, highlighting the need for a multidisciplinary approach to combat this crisis.

As policymakers acknowledge the role of food security in supporting academic performance, they should also confront the systemic issues that hinder educational equity. Despite decades of progress, inequality is still vast in access to high-quality education globally, contributing to the patterns evident in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is only by addressing both the immediate and underlying factors that contribute to learning disparities that communities can strive to repair and strengthen our education systems.

Doing so can bring forth a future where every student, regardless of their background, has the opportunity to thrive academically and contribute to a more knowledgeable and just society.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: The authors would like to thank Katherine Leach-Kemon for editing and Cat Anthony for fact-checking this piece.