Tuberculosis (TB) and type 2 diabetes: you rarely hear the two diseases mentioned in the same breath, but they appear together more often than you might think. Although they are two very different kinds of diseases—TB is an ancient bacterial pathogen that infects human lungs and diabetes is a non-communicable disease linked to the body's metabolism—the presence of either one may foretell the other.

Diabetes increases the risk of TB. High blood sugar, a hallmark of diabetes, was an important risk factor for TB in 2017 according to the Global Burden of Disease study. Diabetes may also predispose people with TB to treatment failure, relapse, and death.

TB infections can temporarily increase blood sugar levels, one of the very things diabetes drugs are designed to control

Why does the link between TB and diabetes matter? One problematic connection is treatment. A number of therapies exist for both diseases; separately, TB can be cured with drugs while diabetes can be well controlled. But treating the two together can be problematic. Diabetes may alter the immune response in patients with active TB, which could reduce their responsiveness to TB treatment and increase their risk of relapse or death. At the same time, TB infections can temporarily increase blood sugar levels, one of the very things diabetes drugs are designed to control. These interactions are further complicated by how long people need to take their drugs. Diabetes is a chronic disease, so drugs are taken continuously, and TB therapies can last for months—even years for people with multidrug-resistant TB. There are also potential drug-drug interactions, which could reduce the effectiveness of both treatments. Left unchecked, this could lead to a potentially vicious cycle reminiscent of the HIV-TB epidemic.

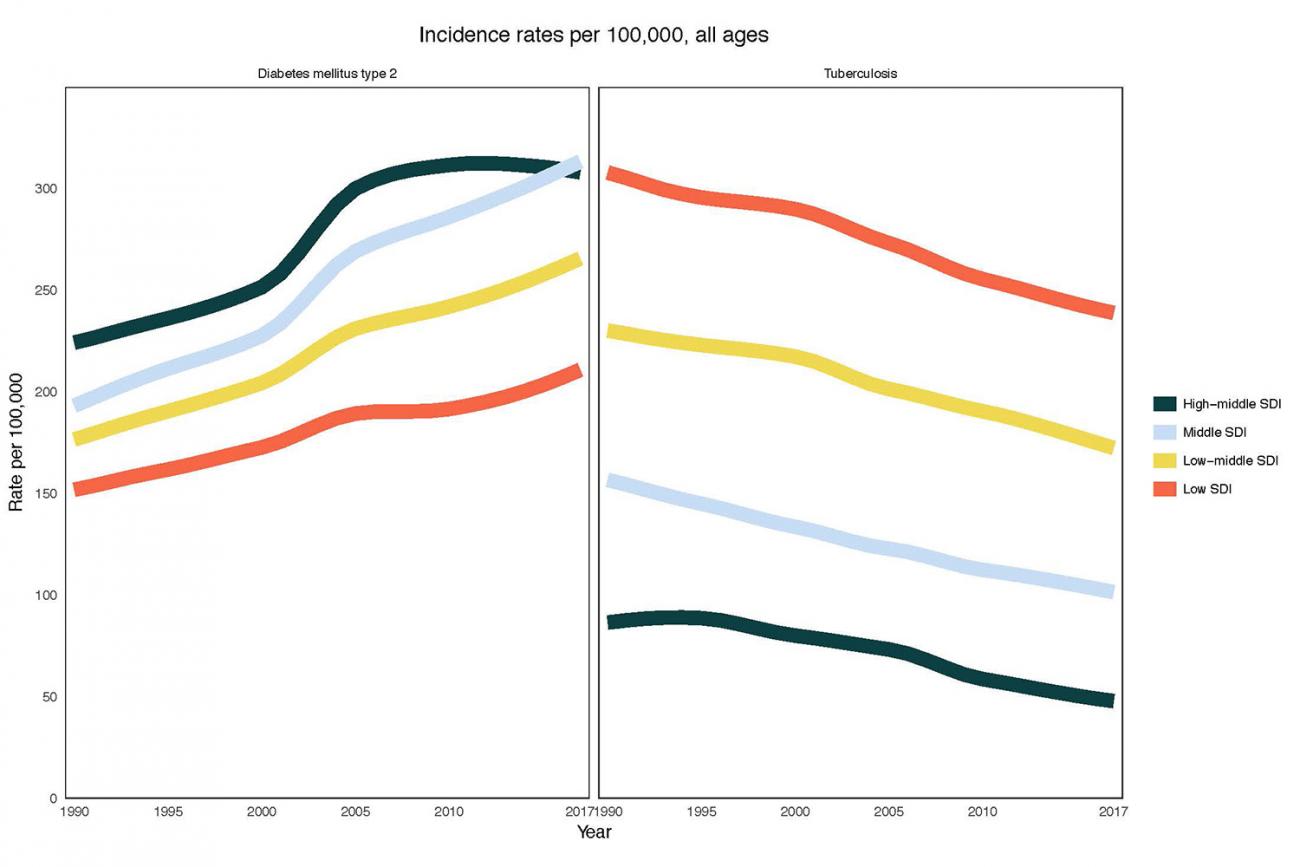

The dual pressures of managing treatment for both diseases, given their potential to interfere with each other, coupled with the high cost of those treatments in the first place will put significant strains on all health systems but will not impact all areas of the world equally. More likely the hammer will fall hardest where those costs can be borne the least. The Global Burden of Disease study estimated that TB incidence rates (or rates of new cases) remained highest in low- and middle-income countries in 2017, while diabetes incidence rates have increased in these countries over the past decade. Changes in risk factors related to malnutrition and urbanization—which may simultaneously increase the risk of both TB and diabetes—will likely impact these low- and middle-income countries to a much greater extent than their high-income counterparts.

What are we doing to address these challenges? The World Health Organization and The International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease published a framework for the care and control of TB and diabetes. It called for collaboration between TB and diabetes prevention and treatment programs as part of broader health system strengthening. However, since there are gaps in our understanding of how to best integrate care for these diseases, the report did not provide specific diagnosis and treatment guidelines. Currently treatment guidelines are left entirely up to the health authorities in each country.

In order to justify redirecting large amounts of resources, policymakers need to know how effective diabetes prevention or treatment is at reducing TB

No matter how it's done, integrating TB and diabetes care will be costly. A 2012 study estimated the costs of treating all new cases of diabetes detected in people with TB for six months (the minimum treatment length for TB). Numbers ranged from $3 million to $55.5 million per year in sub-Saharan Africa and from $5 million to $91.9 million in Southeast Asia, varying based on the number of additional diabetes cases detected. While this would represent a small portion of the total TB funding available through domestic and donor support for TB prevention, diagnosis, and treatment—which totaled $6.8 billion in countries that reported data in 2019—on top of baseline TB treatment costs, this could be a significant financial burden on individuals.

In order to justify redirecting large amounts of resources, policymakers need to know how effective diabetes prevention or treatment is at reducing TB burden. They may also want answers to questions such as: How do malnutrition, urbanization, poverty, smoking, and alcohol use together contribute to TB and diabetes? Does this vary by country? How does diabetes interfere with TB treatment? Does it also interfere with TB diagnosis? What are the implications for TB drug-resistance and HIV co-infections?

Investments are also needed for studies on cost-effective disease management for people with both TB and diabetes.

New or expanded funding is needed to answer these questions. As of 2017, the largest TB research funders are the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), a component of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The largest U.S. diabetes funder is the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, a completely separate NIH institute. In 2017, NIAID launched two funding opportunities for studying the molecular basis of joint TB, diabetes, and HIV epidemics. Investments are also needed for studies on cost-effective disease management for people with both TB and diabetes.

Such knowledge may provide much needed strategies for the joint control of these diseases, and while the cost of such research is high, the price of doing nothing is even greater.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author is employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which leads the Global Burden of Disease Study. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.