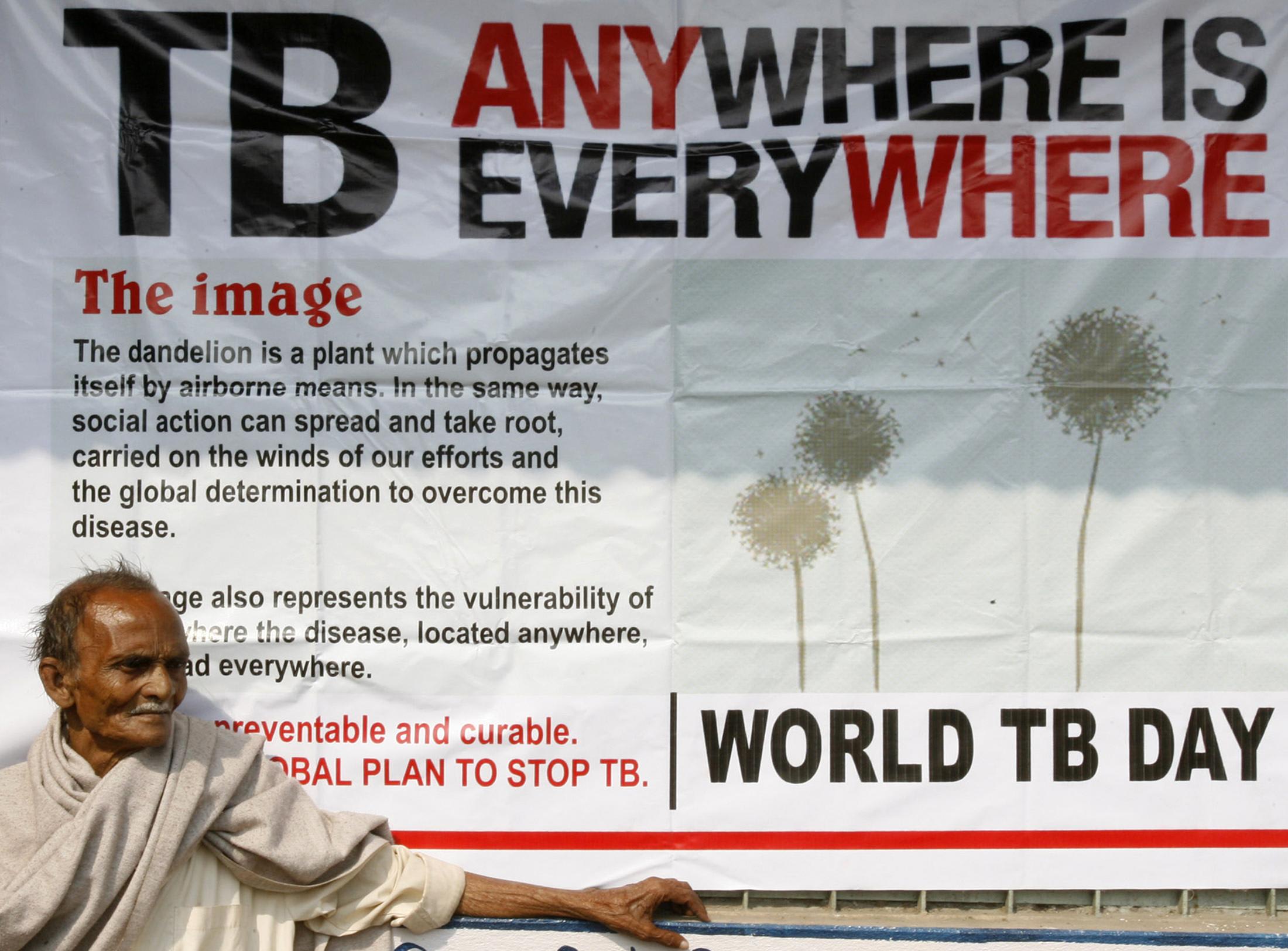

Exceeded only by COVID-19, tuberculosis (TB) is the second-deadliest infectious killer worldwide, taking the lives of more than 1 million people per year. In 2021, just 602 of those deaths occurred in the United States; 366,000 occurred in India.

The large disparity in TB deaths worldwide is tied to gaps in access to treatment as well as the unequal social and economic conditions—namely, poverty and conflict—that fuel the disease.

For people living with TB, a diagnosis can also be rife with stigma. Decades ago in the United States, those infected were sent away to distant sanatoria, expelled from society for months or years.

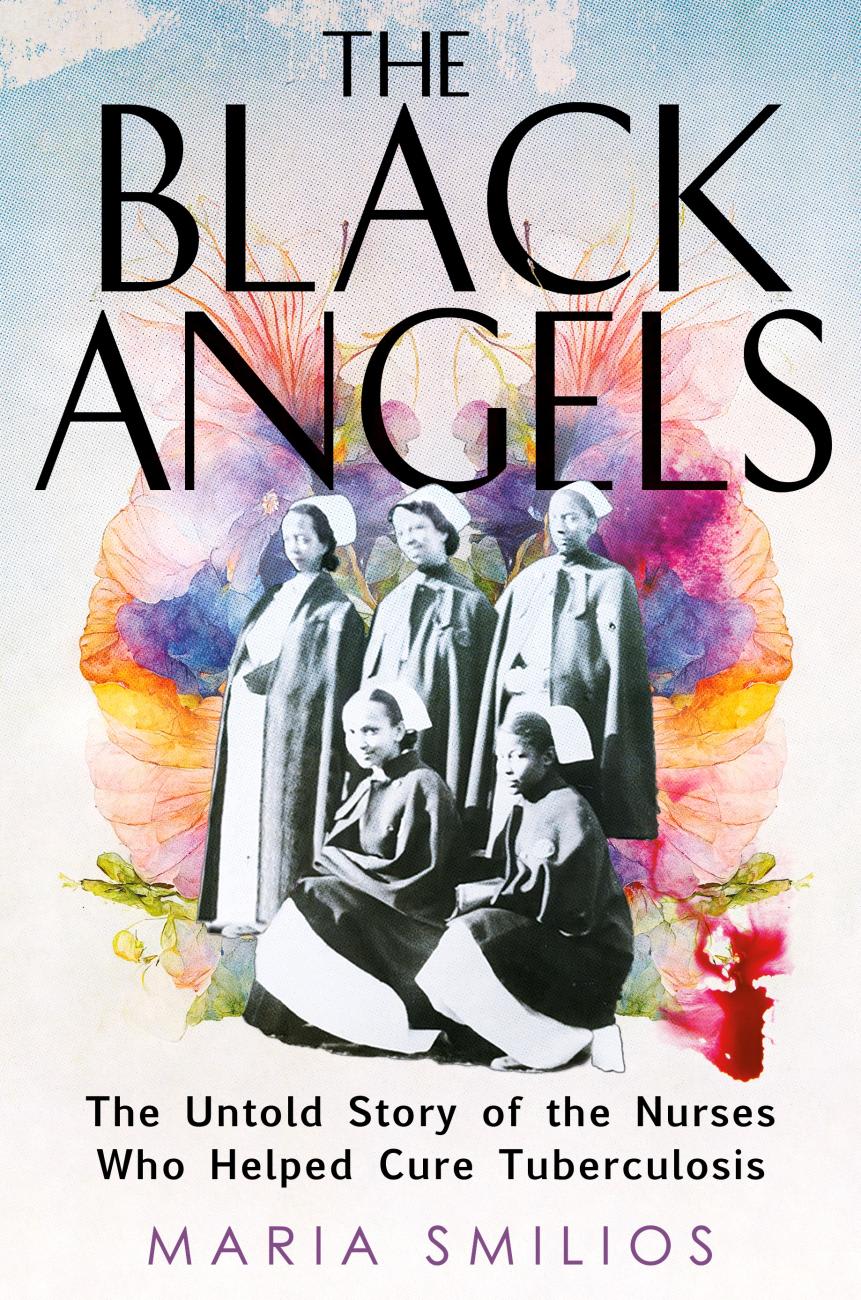

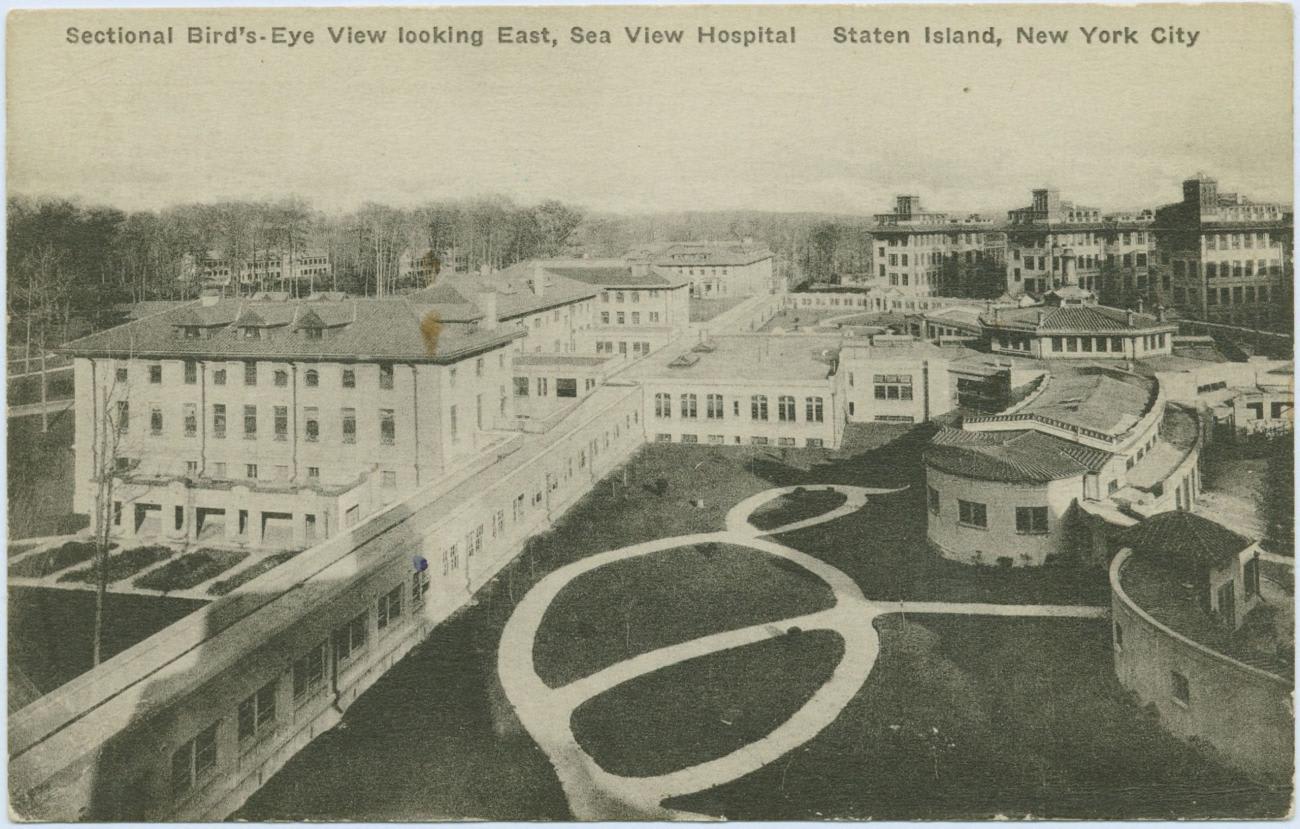

Writer and advocate Maria Smilios explores this painful chapter of public health history in her book The Black Angels, which follows a team of nurses caring for TB patients during the 1930s and 1940s at Sea View Hospital on Staten Island, New York. These nurses, a group of Black women lured largely from the segregated South with the promise of better salary and housing in the North, risked their lives to care for the city's poorest. Drawing from interviews and archival research, Smilios paints a harrowing portrait of life inside the sanatorium.

The world Smilios portrays in her book has far from disappeared into the pages of history. Even though treatment is widely available today, the high prices of patented TB drugs have given rise to Sea View–like settings in many parts of the world. Smilios's experience writing The Black Angels led her to become an advocate for health equity, particularly for affordable and accessible TB drugs worldwide.

For World TB Day, Think Global Health spoke with Smilios about the history of TB, the challenges people living with TB face globally, and the efforts to end the deadly disease around the world.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Think Global Health: In your book, you take readers to a time before widespread treatment for TB. How would you describe living with TB in that era—one that, for many around the world, still exists today?

Maria Smilios: New York City took very stringent measures against TB in the 1920s that cut the death toll in half—and then the Great Depression happened. Two to three families were living together in tenements on top of each other. Or they were homeless. Or they lived in shanty towns along the riverbanks. People were getting sick, and they couldn't afford doctors, so TB started to rise again. Then World War II happened.

TB is a medical disease but, at heart, it is a social disease—a disease linked to poverty

Maria Smilios

TB thrives in environments such as economic depressions and war, especially in a pre-antibiotic world. Before 1935, there were no antibiotics at all—people died from simple cuts that turned into staph infections.

This is the world of the Sea View nurses. People are sent to this hospital to die, and they're grievously ill. When people got sick, they were considered polluted. For women, this meant they were also unmarriageable. They were stigmatized and ostracized from their communities.

TB is a medical disease but, at heart, it is a social disease—a disease linked to poverty.

Back in the 1930s, Black Americans were getting sick at three times the rate of white people. People in the city were also xenophobic toward immigrants, calling them uncultured, uncouth, or un-American. Then layer the stigma of TB atop that—a disease nobody wanted to touch.

Now, in the present, we have cures for TB, yet 10.6 million people are still getting sick annually. It's a disease of who gets care and who doesn't. Who lives and who dies is based on health inequities and access to affordable drugs.

TGH: What challenges did the nurses encounter in caring for these patients?

MS: The nurses worked without any kind of protective equipment, and Sea View hospital has an open ward floor plan. For a patient who's not ambulatory, the nurses would spend up to three hours at their bedside. They're in this environment where TB is everywhere. People cough all the time, they sneeze, they talk and, with every breath, the microbe goes out into the air. It floats around the wards. It's on the bedpans. It's on the sheets. The nurses breathe it in, and they all test positive for tuberculosis at some point. How many of them actually died? We don't know: there were no records.

There were also never enough staff. Never. The ratio was one nurse to sometimes up to 20 patients. Sometimes, patients were locked away for years and became angry, violent, and depressed. People immigrate to New York hoping for a better life, and what do they find? Tenements, filth, disease, and Sea View. It must have hit hard.

The nurses were trying to diffuse the anger—from being sick and not being able to leave. Often patients talked about life before TB and after TB. What the nurses were doing was palliative care, but palliative care didn't exist then. The burden they carried was that they got to know these people very, very intimately. The nurses were psychiatrists; they were taking patients to appointments every day, walking with patients on the grounds; and they were juggling multiple jobs.

The nurses, being Black women, also encountered a lot of discrimination. Patients would cry to them about how they missed their families, but they would also verbally abuse them. Racial slurs happened all the time, particularly on the men's ward.

TGH: Tell me about the drug trials for isoniazid in the 1950s, which ushered in the modern era of TB treatment. What was the impact of this discovery globally?

MS: It was one of the most galvanizing moments in human history. People had been looking for a cure for TB since 1882, when Robert Koch discovered that the microbe was airborne and not caused by miasma, the devil, or anything else.

The nurses at Sea View were integral to the studies. They not only administered the drug, but also watched for side effects. They would collect this data every day. The drug was introduced in 1951 and Sea View closed in 1961. As I always say, the nurses worked themselves out of a job.

Eventually isoniazid went on to become the gold standard drug. In the race for a TB cure, people expected the person who discovered it to win a Nobel prize and lots of money. But in the end, they find that that isoniazid is unpatentable because it had already been discovered in 1912 and lived on a shelf for 40 years before being introduced as a TB treatment.

Because drug companies could not patent it, it remained very, very inexpensive. Because it remained cheap, it went global. Dr. Edward Robitzek, who oversaw the drug trials at Sea View, always said that nobody should profit from disease, especially tuberculosis. His son told me he was excited about what happened and that nobody was able to profit off the drug.

TGH: That's interesting—and somewhat heartbreaking—to hear, given the landscape that people living with TB exist in today, of high drug prices and patent manipulation. Could you tell me more about the current state of TB around the world?

MS: When the book came out last year, I was fortunate enough to be able to sit on an author's panel with John Green, Vidya Krishnan, and Handaa Enkh-Amgalan during the United Nations High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis. John is doing amazing things; just recently he went to Capitol Hill and raised $1 million to give to Partners in Health toward ending TB and TB-related deaths in high-burden countries. Vidya wrote a book called The Phantom Plague about the TB burden in India; Handaa wrote about living with TB as a teenager in Mongolia and the stigma that came along with it.

The global impact of TB is horrific—1.3 million people died in 2022. Others have multidrug resistant tuberculosis. The reason so many people are getting sick is because affordable drugs can't reach them.

Dr. Jennifer Furin, who works in Sierra Leone with Doctors Without Borders, told me that the Black Angels exist in Sierra Leone. Those same hospital conditions and those nurses still exist today in 2024.

TGH: What's next for TB advocates?

MS: It's the battle that John Green is fighting Congress now. It's two pronged. Number one is to raise awareness. TB is a curable disease, but people don't shine a light on it here in the United States because we have it under control. Countries with heavy TB burden are far away, so Americans don't pay attention to them. When I was writing the book, I got all the time, "Why are you writing about a disease that's curable?"

Part of the shortfall is communicating that TB is a deadly disease. It's not just bronchitis. The stories of people living with TB are grueling. I met one woman, 27 years old, who was blinded by the disease after it invaded her brain. The disease eats away at you. It eats away at muscles, at bones, spines, glands, kidneys—it doesn't just affect the lungs. Children can also get very sick from TB, and that's being overlooked. Testing is so important: the longer you wait, the sicker you get.

Another challenge is getting people to care about it. There's no reason to charge countries that can't afford drugs. TB is a disease of poverty, and we have to destigmatize it. We must address the two-tiered health-care system, the widening gap between the haves and have nots. No one is expendable.