For most sports fans, the crunch of two bodies colliding adds to the excitement of a game. But, as an emergency physician, when I watch an aggressive tackle or cross-check, my mind is on the player lying on the ground. Do they look dizzy? Are they struggling to get back on their feet? I'm less interested in which side is winning than in grabbing my medical bag and getting onto the field to assess and repair the damage.

Sports medicine has a rich history dating back over 2,400 years to ancient Greece, but the explosion of professional sports over the past century—soccer, tennis, basketball, and Formula One car racing—has thrust the role of team physician into the public eye. Many countries now recognize training programs and certifications in sports medicine. New technologies, including widespread MRI availability and robotic and minimally invasive surgeries, have optimized diagnostic and treatment options compared to thirty or forty years ago.

Sports medicine has a rich history dating back over 2,400 years to ancient Greece

Those of us who specialize in sports medicine come from diverse fields, ranging from orthopedics to family practice to emergency medicine. Many professional teams hire more than one doctor, each performing a different role. Some physicians provide emergency care to athletes during games; others, like surgeons, fulfill less immediate needs, such as operating on team members in the off-season.

While the most visible part of our work centers on treating sprained ankles and head injuries under the gaze of TV cameras and an expectant crowd, whether we're home or in a host country, a large part of sports medicine takes place off the field.

The Surprising Side of Sports Medicine

My medical school curriculum definitely did not prepare me for many of the scenarios that I've run up against as a team physician. I have negotiated exemptions to carry a compressed anesthetic gas cylinder on a plane, determined when a player with a blood clot can resume contact sports training, and registered an ultrasound machine in a foreign country. I have prepared and implemented lectures for athletes on subjects as diverse as recognizing signs of heat stroke and engaging in safe sex practices.

The work is varied in more ways than one, often taking us far beyond our normal comfort zones. Aisha Khatib, a Canadian physician who graduated from the University of Alberta with specialties in emergency medicine and primary care, spent five years working in New Zealand. During her time there, she provided care to amateur and professional rugby players.

"Treatment is not just about game day," Khatib says, noting that she makes a point of reminding players about their booster shots for recommended travel vaccines against illnesses such as influenza and meningitis.

"Sports medicine is really global health," says David Lawrence, a sports medicine physician at the University of Toronto, who also works with the Toronto Blue Jays baseball team. Anticipating travel to Florida for preseason training, he notes that team doctors also often travel to and treat players in multiple countries.

"It is rare that a top-level athlete has played in only one country," Lawrence says.

Preparation comprises a far bigger part of my work as a team doctor than in my day job as an emergency room physician. Planning for the worst situations—like severe allergic reactions, missing or broken equipment, and variances in medication types and dosages in different countries— can make all the difference. Because players frequently compete away from their hometowns, out of state, or outside of their home countries, their medical records and past surgical histories are likely to come from numerous medical systems—and are sometimes in different languages. Keeping in close contact with health-care providers overseas is commonplace and an area where technology and the sharing of electronic health information helps make our jobs easier.

"It is rare that a top-level athlete has played in only one country"

David Lawrence, University of Toronto

"Part of preparation is prevention," says Michael Larocque, who practices in the Durham region east of Toronto and has worked with university and professional athletes in wrestling, soccer, and lacrosse. This goes beyond strengthening muscles and taping up newly healed joints to reinforce them during the fragile recovery period.

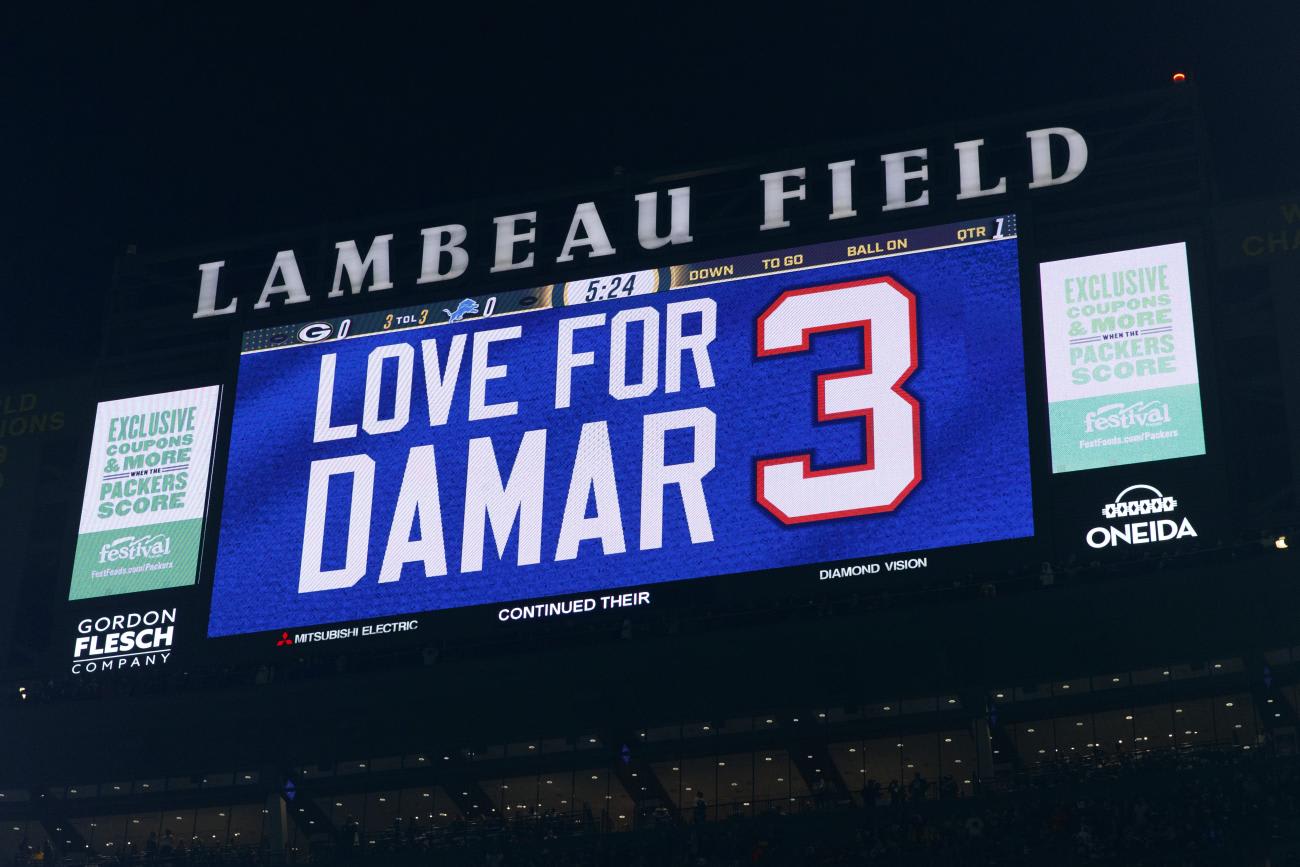

Larocque cites the case of Buffalo Bills football player Damar Hamlin who suffered a cardiac arrest during a game in Cincinnati in early January 2023. The Bills' medical team preparation and planning were clearly on display and likely contributed to Hamlin's survival and recovery, Larocque says. Lifesaving CPR and oxygen were applied in seconds and an ambulance was transporting Hamlin to the hospital within minutes of his injury.

Sports physicians also become accustomed to relocating joints and stitching injuries with little privacy and under intense time pressure while a game is in progress.

Some of the scariest threats we encounter are not on the field but in the stands. I once rescued a fan choking on a hot dog and treated another who had fallen down the stadium steps. Then there was the time I helped resuscitate a team mascot who was comatose with low blood sugar. Having supplies, such as airway equipment and essential diabetes medications, on hand to treat such urgent health hazards is part of the job.

Sports Physicians Play as a Team, Too

A team-based approach to providing care is common, no matter what the sport. Unlike the hierarchical system found in hospitals, where doctors tend to give the orders, those involved in sports medicine—including trainers, physiotherapists, massage therapists, chiropractors, nutritionists, and even team coaches—often pool their skillsets.

Lawrence highlights the importance of cutting-edge science and interdisciplinary collaboration. "It's really a dual role where you are interested in optimizing health, but also performance," he says.

Technology is playing an ever-larger part in athletes' medical care. Advances in measuring the speed of players, the force of on-field collisions, and the effects of overtraining enable coaches, doctors, and trainers to design customized rehabilitation plans for injured athletes, and to limit overexertion. Multiple camera angles and slow-motion replay give doctors a much better idea of what causes injuries on the field.

"I once diagnosed a player's spinal fracture from a video review," recalls Khatib.

Supporting Pro Athletes' Mental Health

Keeping an eye on super-competitive athletes is not only about keeping them in good physical shape, but also ensuring they can perform under high stress without endangering their psychological well-being. Mental health support is consequentially becoming an important focus of sports medicine.

Coaches and athletes often impose pressures on their health-care providers

Khatib recalls helping players deal with traumatic events that have little to do with sport, such as the death of a family member and divorce. "These players are often young adults and they deal with intense scrutiny of their public persona," she says.

There is also a growing practice of standardized pre-season screening for substance abuse, anxiety, and depression, says Larocque. Athletes who need help are quickly referred for counseling.

While sports medicine offers exciting opportunities to travel and mix with high-level competitors, it also presents challenges quite different from those found in other medical specialties. Coaches and athletes often impose pressures on their health-care providers. Discussions on when to continue playing and the risk of further injury tend to be far more heated in the dressing room or on the side of the field than in a family doctor's office.

"Conversations around restricting activity or training are those that I look forward to the least," says Larocque.

Financial pressures can also be an issue, especially at the higher levels of professional sports. Players and coaches can be motivated by scholarships, endorsements, or the need to have certain players on the field during important games, even if playing risks an athlete's health.

Even so, Lawrence describes sports medicine as "the best job in the world." He especially enjoys the relationships he has forged with teams of highly trained professionals, including the athletes and other medical colleagues.

"When I can help a patient of any athletic level get back to meaningful activity, it has a huge impact on their health and wellbeing," Larocque adds.