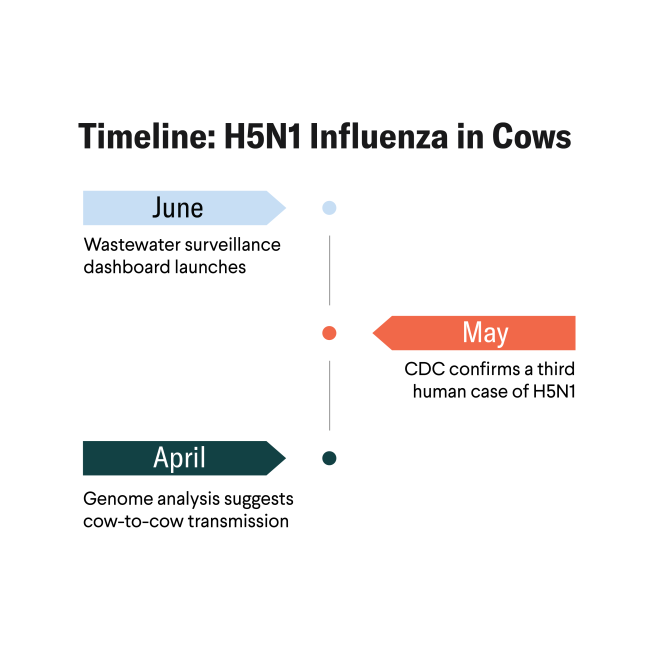

More than three months since an H5N1 influenza outbreak began in cows and humans, public health experts are calling for a stronger response, including to fill critical gaps in data collection.

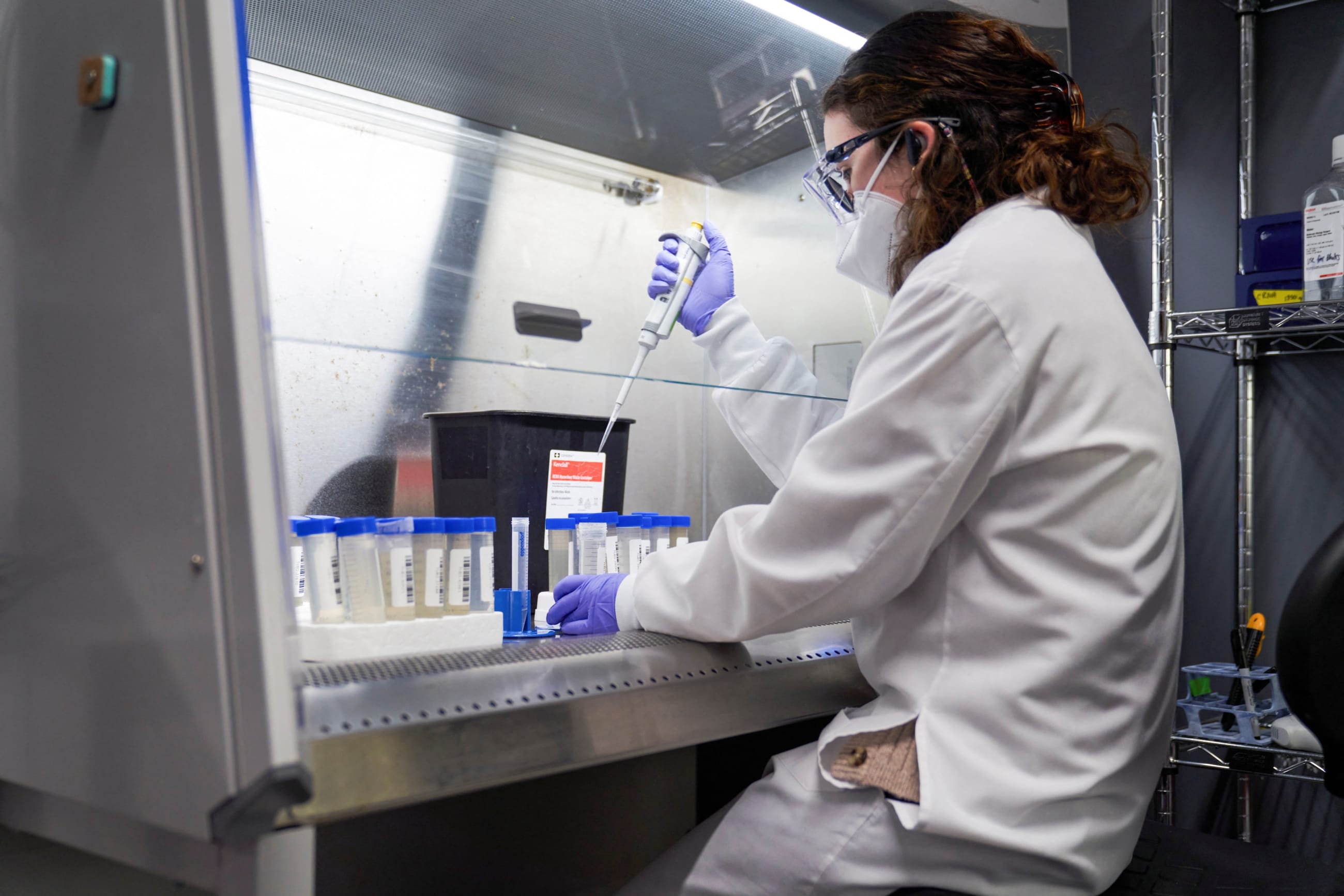

Genetic surveillance of wastewater offers relatively low-cost, rapid early detection that can identify communities where H5N1 avian influenza could be circulating, when an outbreak could be taking place, and how large that outbreak may be. Detecting H5N1 in a new wastewater site can also signal officials to begin further investigation of potential virus sources in that location, such as infected cows, humans, or milk-processing plants.

Although wastewater data can inform decision-makers about H5N1's spread, the approach is far from perfect. Wastewater samples cannot differentiate between the source of the pathogen—cow, human, or poultry—or the flu subtype without variant-specific testing or costly genetic sequencing. Coupled with other forms of surveillance, including monitoring for H5N1 in cattle, poultry and wild birds, wastewater tracking helps form a more complete picture of the outbreak's severity.

In conversation with Think Global Health, Megan Diamond, director on the health team at the Rockefeller Foundation and leading its global wastewater surveillance efforts, explains how investing in the method, transparent data sharing, and effective communication about wastewater can equip the United States better control the spread of H5N1.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: Let's start with an overview. What does wastewater data tell us about an outbreak, and how effective is it as a tracking tool?

Diamond: Wastewater surveillance is an amazing population-level surveillance approach. It can detect the presence of different pathogens when the analysis looks for different gene fragments. Is a pathogen present in a given wastewater sample, or is it not? It can then can go beyond to tell us—when the analysis is done—what the concentration of that pathogen is, so we can interpret that information.

It's a great early detection tool, a way for public health officials to get a better understanding of what's circulating in the wastewater—which is a reflection of what's circulating in the community—whether in animals or humans.

If nothing is detected, it's great to keep sampling because then public health officials can be alert to when something does emerge in their communities. Wastewater surveillance allows for tracking dynamics that otherwise wouldn't be captured by traditional health systems.

Think Global Health: What are the limitations of wastewater as a tracking tool? For example, can you differentiate H5N1 from other flu types, and human cases from cattle or poultry?

Diamond: Wastewater surveillance has limitations in the same way that other public health surveillance approaches do. That's why we're seeing important use of triangulating data across data sets, so that each can fill gaps where the others have limitations.

We can't differentiate, using wastewater, whether the source was animals—whether poultry, cows, or humans—or from a milk-processing plant. We don't get that level of information from wastewater surveillance.

The beauty of wastewater is that it sounds the alarm

Megan Diamond

Further and deeper analysis of a wastewater sample is possible to see whether it is H5N1 or another variant [of influenza]. That can be done easily, but you have to be looking for it. The PCR test has to be set up to detect specific variants.

Otherwise, you can also use sequencing approaches, but those are more expensive, and probably not best in this context. But you can definitely [use sequencing to] look for variants. And one way [sequencing] is being used now is to monitor how the genes are changing, and whether human-to-human transmission could become more likely.

Think Global Health: What can we learn about H5N1 from the wastewater data that is not clear from testing cows on dairy farms directly? Two wastewater sites in California recently tested positive even though no positive dairy farms have been found in that state.

Diamond: The beauty of wastewater is that it sounds the alarm. It sends the alert that something is going on. In the sites in California, we know that a source is contributing to H5N1 in these communities. Like we just talked about, of course, just using wastewater surveillance we can't identify the source.

But this is where the different layers of public health are so powerful and so important. We've narrowed it down. There are so many geographies across the United States; where do you begin? Well, now we just got an alert from California that it has a case of H5N1 and then you can start a deeper investigation. Is there a milk-processing plant that could be dumping untreated milk nearby? Is there a dairy farm from which waste is going into the treatment plant?

Patients coming to the hospital may be categorized as [having] something generic, such as respiratory symptoms, but on further investigation you're able to find out what that source is.

Wastewater helps us narrow down when you have limited information on where different outbreaks could be occurring, especially if people are asymptomatic, mildly symptomatic, or don't have access to health systems.

Think Global Health: What is the trend we're seeing with H5N1? How does it compare with the early days of other outbreaks like COVID-19?

Diamond: We were not using wastewater surveillance in the early days of COVID at scale. We're more equipped now to detect and contain potential outbreaks than we were during COVID because we are using it.

Some systems in place were already running: WastewaterSCAN and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's program. [These are] ongoing programs that have the infrastructure and the knowledge to, at various speeds, transition to doing more in-depth monitoring for H5N1 influenza A.

In terms of how this data is used and the transparency of this data, that's a different question. But localities are better equipped when they use wastewater surveillance to manage epidemics and pandemics.

Think Global Health: That leads to my next question: Is our government making appropriate use of wastewater surveillance? Even though we are making more use of wastewater data, how can governments better implement it to more effectively monitor the current outbreak?

Diamond: Governments can continue supporting sites that are doing wastewater surveillance and promoting the expansion of additional sites because the United States doesn't have 100% coverage of all wastewater treatment plants. Several places in the country don't even use treatment plants and opt for other forms of sewage treatment and handling.

[Governments should] equip the partners that they're already working with and expand to new locations with an eye toward equity for those who are traditionally left out of such surveillance mechanisms. They should also be transparent with data. It's one thing to support the collection of data and then there's the other end that needs to be analyzed, interpreted, and shared with people with decision-making authority. [Governments should] continue to support public health officials in understanding wastewater surveillance data, its trends, and possible responses. It's important to remember wastewater surveillance is still new in how we're using it, both in the United States and around the world. It had these niche use cases such as polio and emerged at scale for COVID. Many public health officials, though, are not comfortable or used to analyzing and understanding this data. Providing context and tools that enable public health officials to integrate these data with other types of data is going to be critical so that it's actually actionable.

I would love to see long-term investment in wastewater surveillance as a core infrastructure element of public health in the United States

Megan Diamond

After the height of the COVID pandemic, and after public health departments felt that they were managing the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, many programs stopped. Investment in wastewater surveillance dropped off. These programs are the most powerful when they're always on and have multipathogen capabilities.

I would love to see long-term investment in wastewater surveillance as a core infrastructure element of public health in the United States. I think [H5N1] is going to be a beautiful use case to help make the case for funding and its importance. If we invest in wastewater surveillance now we mitigate morbidity; we mitigate mortality; and we save money. I hope this is another data point for its value.

Think Global Health: Anything else you would like readers to know?

Diamond: Keep an eye on the wastewater, because that's your leading indicator. We've never used this capability at scale this early in a potential outbreak or epidemic. Let's double down on it.

There's a lot we don't know about wastewater; it's not a perfect science. Let's acknowledge what we don't know, acknowledge the limitations, and then move forward from there with the best information and the best data we have. This is going to be key as we monitor the spread of H5N1, nationally and internationally.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This interview was lightly edited for clarity.