Violence and instability are rising around the world. Researchers recorded 2022 as the "deadliest year since the Rwandan genocide in 1994" and 2023 as experiencing the highest number of armed conflicts since the end of World War II. Today, protracted wars continue, new violence erupts, and old hostilities such as the war between Israel and Hamas reignite.

Civilians are the main victims of armed conflict, yet little attention is paid to how civilian suffering impacts the prospects for peace. The protection of civilian health and well-being is not only a moral imperative, but also a strategic one. Declines in health and gender outcomes can further entrench societies in vicious cycles of organized violence, whereas efforts to improve health equity and gender equality help build and maintain peaceful societies.

The contribution of health equity and gender equality to peace deserves heightened attention in today's more violent world.

Consequence or Cause?

The increase in violent conflict around the world has fueled renewed interest in the causes and consequences of conflict. Foreign policy analysts have traditionally viewed war and peace as the drivers of health and gender conditions. Large-scale violence damages health and gender outcomes, whereas political stability and peace enable health equity and gender equality as well as improve socioeconomic development. Under that consequentialist approach, protecting civilian well-being in war is largely perceived as a matter of ethics, not of strategy.

Researchers and policymakers have lacked an analytical framework and robust evidence to explain how health and gender outcomes can contribute to conflict and influence peace. Efforts to harness the peacebuilding potential of gender equality and health interventions have produced contradictory evidence. Female empowerment is statistically associated with more peaceful societies, yet the global backlash against women's rights illustrates that the path from gender equality to peace is far from straightforward. Health is often promoted as a bridge to peace, but, as seen in Gaza and other war zones, health services are more often targets of military violence than tools of peace.

That gap in knowledge stimulated a report released last year from The Lancet Commission on Peaceful Societies through Health Equity and Gender Equality, on which I served. The commission used cross-national statistical analyses, comprehensive literature reviews, and case studies to examine whether health equity and gender equality influence levels of peace and violence.

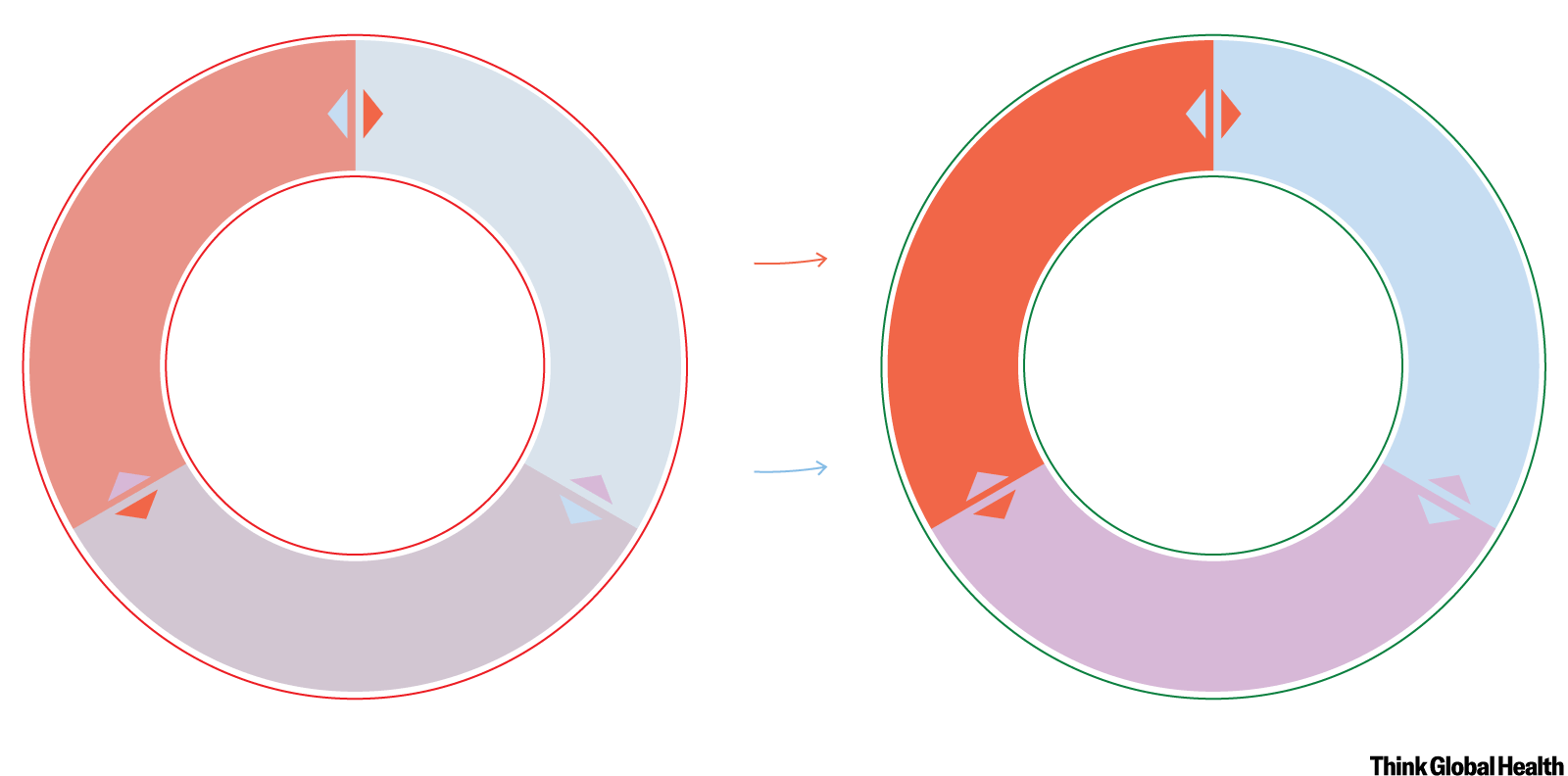

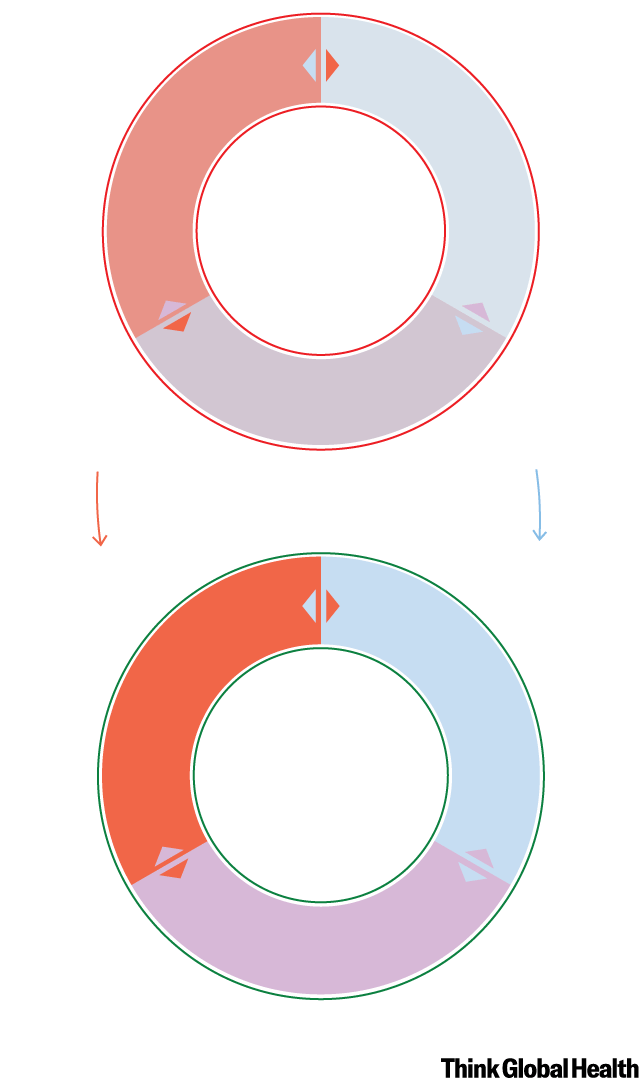

The report highlights that violence, health inequities, and gender inequalities produce a vicious, self-reinforcing cycle. Importantly, the commission found no evidence that better health and gender conditions provide a simple shortcut to peace. The commission's theory of change suggests that improvements in health equity and gender equality help nudge societies toward beneficial cycles of peace. The commission showed that, even after controlling for broader political and economic factors, such improvements have a unique ability to prompt tangible and sustained changes in social and political institutions.

Improved health and gender outcomes generate important social, economic, and political effects that transform societies. Access to quality health services, for example, facilitates economic participation and enhances trust in local governments. Improvements in gender equality provide women with opportunities to participate in political, social, and economic life in ways that support domestic stability and peace.

Applying the Theory of Change in a More Violent World

The devastating impact of contemporary conflicts on civilians underscores the importance of the commission's findings to foreign policy–makers. Worsening health and gender conditions risk trapping countries in patterns of violence, whereas sustained external health assistance is associated with a lower risk of conflict recurrence. Those findings highlight the strategic importance of preserving health capabilities as a vital peacebuilding resource. Even amid the violence, states should safeguard and prioritize health equity and gender equality outcomes. The more that war degrades those capabilities, the longer the conflict could persist and the more difficult postconflict recovery becomes.

The frequent military attacks on health facilities and personnel underscore the urgent imperative to protect health by applying international humanitarian law (IHL). IHL prohibits intentional attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure and accords health facilities and personnel special protections.

As others have advocated, policymakers should go beyond simply counting and criticizing attacks on health personnel and infrastructure to better identify how to prevent, mitigate, and respond more effectively to these attacks. Such proactive measures could include creating a health neutrality verification mechanism by deliberately placing representatives of international organizations, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross, at health facilities. Those representatives could provide independent, transparent, and credible reporting on whether combatants are using the facilities. That approach could potentially mitigate the problems seen in Gaza, where Israel has argued that its attacks on hospitals are within the bounds of IHL by claiming that Hamas uses such sites to support its military operations.

The commission's findings related to gender also highlight the ways in which the provision of humanitarian and peacebuilding assistance needs reform. Given the importance of gender equality to postconflict recovery, humanitarian and peacebuilding efforts should actively seek to improve health equity and gender equality.

For example, the report urges the humanitarian sector to counter the narrative of women and girls as victims, promote their agency, and ensure that humanitarian programming furthers gender equality. Within the humanitarian system, the commission calls for a dedicated gender equality cluster that assesses and monitors the state of gender equality in crisis-affected settings, gathers and disseminates data related to gender equality, and coordinates action. To fulfill that aim, benchmarks for gender-equal humanitarian action and health services are needed. Humanitarian activities should also implement zero-tolerance policies on harassment, sexual exploitation, and other forms of gender abuse.

Improved health and gender outcomes generate important social, economic, and political effects that transform societies

The commission's research underscores that projects tailored to the local context and led by local and national actors are the most successful. Too often, well-meaning external efforts informed by global norms attempt to transplant models of health equity and gender equality that are ill suited to local contexts. For example, placing women in leadership positions without building support structures for gender equality is not an effective strategy. In contrast, empowering community health workers has proved extremely effective in enabling gender equality reforms that community members accept.

Although critical for sustaining beneficial cycles that support peace, national and global initiatives to improve health equity and gender equality unfortunately face headwinds. The damage done by the COVID-19 pandemic, the increasing health and social burdens associated with climate change, intensifying competition for development assistance, and political opposition to progressive health and gender policies create obstacles for the types of peace-enhancing policies the commission's report supports.

What happened in Afghanistan illustrates the point. The Afghan government and its international partners, especially the United States, invested hundreds of millions of dollars to strengthen health services and promote the rights and well-being of women. Despite dramatic improvements in health and gender outcomes, the Afghan government and its partners failed to maintain political control and military security over the country in the face of the Taliban insurgency. The Afghan example shows that donor governments that actively support stabilization or counterinsurgency efforts risk undermining health and gender initiatives when they instrumentalize them as foreign policy priorities. Moreover, efforts to improve health equity and gender equality cannot compensate for broader policy failures at the political level.

Those lessons highlight the risks of narrow groupings of foreign policy and military decision-makers dictating policy. The return of geopolitics to international relations has increased the perceived utility of armed force and provided incentives to view problems through a zero-sum, us-versus-them lens. Such a policy context favors short-term objectives and squeezes out input from a wider range of experts, including those working on health and gender issues, who focus on protecting civilian populations and infrastructure.

Avoiding Forever Wars

In a context marked by intensifying geopolitics and increasing armed conflicts, emphasizing the importance of health equity and gender equality might seem a quaint echo of the enthusiasm for the human security agenda prevalent in the post–Cold War era. That agenda arose at a different time, when international cooperation to build more peaceful societies reached unprecedented levels.

But perhaps it is time to revisit the human security agenda with a focus on the potential for health equity and gender equality to help make societies more peaceful. The emergence of a more violent world should increase rather than marginalize the lessons learned about the power of individual well-being, social stability, and collective action among nations. Indeed, those lessons have heightened value in a world riven by wars that needs evidence-based strategies to transform harmful cycles of behavior into actions that construct more durable pathways for peace.