Health workers form the backbone of health systems. During the COVID-19 pandemic, they have been critical, ensuring emergency response and the delivery of essential health services. A sufficient supply of health workers is necessary to deliver high-quality, accessible health services that do not result in financial hardship—to realize universal health coverage (UHC). Doctors, nurses, pharmacists, lab technicians, and others who provide care related to health and wellness make up the health workforce. Without enough of them, health, social, and economic systems may falter.

In 2019 there was a shortfall of 6 million doctors and 31 million nurses and midwives worldwide

In a recently published study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), we found that the world's health workforce, which we estimated to include about 13 million doctors and 30 million nurses and midwives, is not nearly large enough to reach target levels of UHC. To achieve 80 out of 100 on the UHC effective coverage index, an additional 6 million doctors and 31 million nurses and midwives were needed in 2019.

There is reason to believe shortages became worse during the COVID-19 pandemic. The unprecedented public health crisis took a psychological and physical toll on already overstretched health workers. High rates of burnout, stress, and suicide among health workers were reported as rates of COVID-19 infection and death climbed.

Rate of physicians to nurses, density per 10,000 population, 2019

IHME estimates that the ratio of physicians to nurses varied substantially across countries in 2019.

Health Worker Mix Varies Country to Country

Health system performance relies heavily on the number of health workers but the mix, or composition, of the health workforce is also relevant. The share of health workers who are doctors versus nurses versus other occupations determines how tasks are distributed and the composition, or mix, of types of health workers in a country can influence how health systems are organized.

Globally, there were 2.3 nurses for every doctor in 2019, with more than 90 percent of countries employing more nurses than doctors. Our data show that the mix of health workers differs substantially across country contexts. Japan, for example, had nearly five nurses for every doctor in 2019, while in Lebanon, there was nearly one nurse for every doctor.

Globally, there were 2.3 nurses for every doctor in 2019

Similar Health System Performance, Different Health Worker Composition

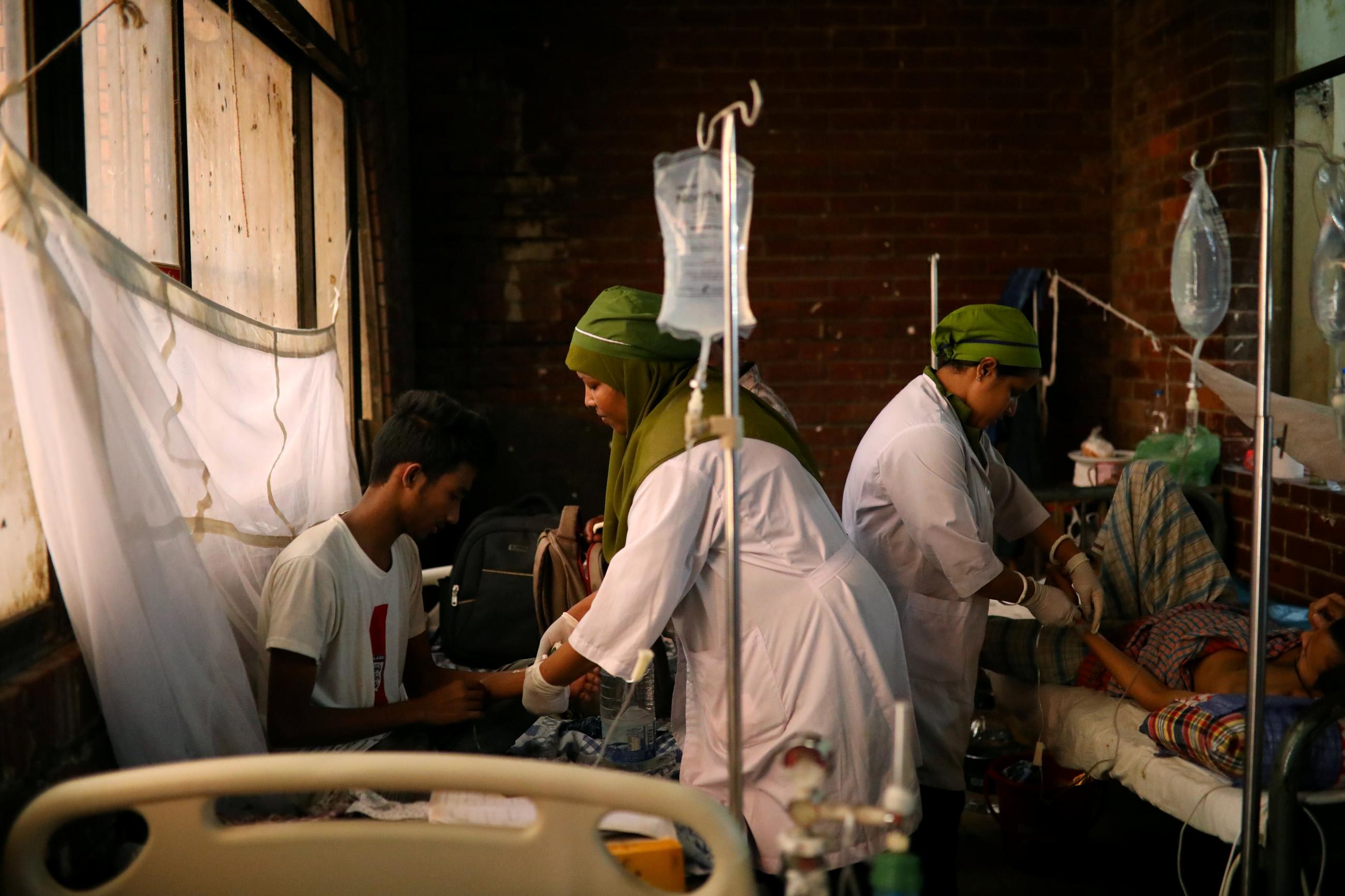

The mix of health workers varies even among countries with similar levels of UHC. Bangladesh and the Philippines are two lower-middle-income countries with comparable levels of health system performance. Both countries scored slightly below the global average of 60 on the UHC effective coverage index in 2019; Bangladesh scored a 54 and the Philippines scored a 55 on the index. These health systems performed similarly yet employed starkly different ratios of doctors to nurses. Bangladesh has the rare health system with more doctors than nurses; the country employs 1.3 doctors for every nurse, with 6.5 doctors and 5.0 nurses per 10,000 population. In contrast, the Philippines employs 5.2 nurses for every doctor, with 3.8 doctors and 19.8 nurses per 10,000 population.

The distinct mix of health workers in Bangladesh versus the Philippines suggests these countries use different approaches to deliver UHC. Comparable achievement on health system performance measures may also be related to the role played by other health workers. In the Philippines, doctors and nurses account for 42 percent of the total health workforce, but in Bangladesh, they account for just 27 percent of the total health workforce. In Bangladesh, some tasks typically carried out by nurses or doctors in other countries are shifted to community health workers (CHWs), who serve a prominent role in providing primary care services, such as family planning support, antenatal and postnatal care, and vaccinations. The shift in responsibility to CHWs in Bangladesh may contribute to the country's UHC achievement, although many other factors also play a role, including the country's robust NGO network and widespread community engagement.

More Health Workers Are Needed

To realize the levels of UHC targeted in the IHME analysis (80 of 100), both the Philippines and Bangladesh will need more health workers. Based on estimates that predate the pandemic, Bangladesh would have to more than triple the number of doctors in its workforce and employ 14 times as many nurses. Similarly, the Philippines would need to employ more than five times as many doctors and three-and-a-half times more nurses.

The additional number of workers to be trained and employed is substantial, and both countries already face significant challenges in the areas of recruitment and retention of health workers. The Philippines has bolstered the country's nursing training program to educate nurses who work locally and abroad, but restrictions on working abroad implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with insufficient pay, have caused nurses to threaten to resign en masse. Although the country has robust and readily available nursing training programs, it is the largest exporter of nurses globally, signaling a need to incentivize nurses to stay in the Philippines.

Meanwhile, Bangladesh only recently reestablished its health worker recruiting practices, after a five-year pause that ended in 2018. Beyond recruitment stoppages, the estimated health worker shortages are further exacerbated by under-resourced work conditions, widespread absenteeism, and low retention, particularly in rural communities.

In the face of doctor and nurse shortages, Bangladesh and the Philippines have leveraged health workforces with different compositions to attain similar levels of UHC. In both countries, implementing policies to improve the recruitment, training, retention, and incentives of health workers will be fundamental to improving health system performance. Further investigation into the factors that make this possible could inform efforts to pursue UHC in these countries and elsewhere.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors are employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which produced the health workforce estimates described in this article. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual authors and are not necessarily shared by their institution.