In 2020, Scott County, Indiana, was on the verge of ending HIV. And then they lost one of their best tools in the fight: a syringe services program.

Five years earlier, 235 residents had been diagnosed with HIV—an outbreak traced to people who inject drugs. But an innovative "one stop shop" model where individuals who inject drugs had access to a variety of treatment and preventative care options stifled transmission. By 2018, only five people were diagnosed with HIV, and in 2020, only one person was.

Scott County's syringe exchange program led to a 99.6 percent reduction in HIV incidence

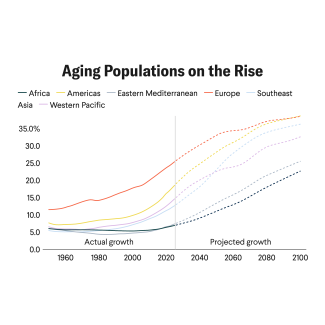

One component of the model was a syringe services program—also referred to as syringe or needle exchange—that had received bipartisan support at multiple levels of state and federal government. Public health officials touted the program's 99.6 percent reduction in HIV incidence as a striking success. But in June 2021, Scott County decided to end the syringe services program—a move that will cost the local community lives and dollars if HIV continues to spread.

Social Services Out of Sorts

How did an effective public health program get shut down so easily? Misinformation and controversy. Opposition to it stemmed from the belief that the exchange program enabled drug use and led to more overdoses. But research shows that when syringe services programs end, people increasingly inject drugs with unclean needles, and their access to Naloxone—a drug that reverses overdoses—decreases. Syringe services programs allow people to use clean syringes and have no effect on how often people use drugs. Successful syringe services programs are in peril in Scott County and across the nation.

Syringe services provide a starting point for social and medical support specialists to establish relationships with people who inject drugs. These relationships connected Scott County with peer recovery services, harm reduction education, HIV testing, and substance abuse treatment.

In one local news report, Scott County resident Rick Williams said he benefitted from the program, noting that it kept him clean and directed him to recovery. These services are especially important in settings where health-care options are sparse. Until recently, there was only one primary care doctor in Austin, Indiana, a town at the heart of the Scott County epidemic. The physician, Dr. William Cooke, noted in a separate interview that the syringe program connected him with patients who otherwise would have gone untreated for addiction.

Williams' and Cooke's stories illustrate the challenges facing many rural communities around the country: addiction epidemics and limited access to comprehensive health care. While not all rural communities are severely affected by the opioid epidemic, rural areas have seen faster increases in overdose deaths than urban areas over the past two decades. Those struggling with addiction in rural areas have less interaction with medical care, making initiating treatment very difficult. Communities triage this crisis by substituting longterm physician-led care with emergency law enforcement.

Syringe services programs help communities increase safe syringe disposal practices

Many community members frequently cite fears about "syringe litter" to discourage syringe service programs in their communities, inaccurately thinking that syringe litter will be high near exchange sites. For many programs, however, almost all syringes provided are later returned rather than being disposed of unsafely. Studies indicate syringe services programs help communities increase safe syringe disposal practices.

Police officers across the country continue to support syringe services programs because they understand the positive impact the programs have on the larger community they protect.

In a news report, Scott County Sheriff Jerry Goodin stated, "For the safety of our prisoners, for the safety of our children, for the safety of our officers, for the safety of Scott County, I am a big supporter of the syringe exchange."

Preventing Widespread Disaster

Douglas Huntsinger, Indiana's Executive Director for Drug Prevention, Treatment, and Enforcement, understands the danger in ending drug exchange programs. In a statement after Scott County closed their syringe services program, Douglas explained, "These programs stop the spread of disease, they keep people alive, and they help people find treatment."

His team's approach is to provide communities with the tools and resources they need to combat the drug epidemic, seeking to both prevent and deal with the issue at hand. This pragmatic thinking is not new or unique. Consider sprinkler systems. They exist in buildings to prevent a fire in one section from destroying the entire structure. What happens when you remove the sprinklers? Significantly more work will be required to combat the flames. Just as sprinkler systems do not increase arson, syringe services do not increase drug use. Just as people shouldn't have to live in a building without disaster prevention, community members should not have to live in a community without harm prevention and reduction.

"These programs stop the spread of disease, they keep people alive, and they help people find treatment"

Douglas Huntsinger

The abolition of the syringe services program affects Scott County's financial security. An accidental poke with an unclean syringe can lead to illness and decades of HIV treatment and care, totaling $490,045 in lifetime medical costs. Syringe services programs are financially effective, every $1 spent on a syringe exchange program saves $7 in health-care costs.

At a Crossroads

Indiana is not the first, and will not be the last state, to close lifesaving harm reduction programs. Politicization of these issues across the world has led to substantial setbacks in disease control and harm reduction work related to HIV. Syringe services programs in Nairobi, Kenya, have battled competing interests among those who work in HIV prevention and those who advocate against drug use. In Canada, after one of its largest syringe exchange programs was shut down in 2008, people who relied on the exchange sites experienced an increased risk of transmission of blood borne infections and abscesses.

Syringe services programs continue to have outspoken and ardent advocates who understand the stakes. After Scott County ended the syringe services program, Huntsinger told the authors of this commentary, "My thoughts and prayers are with my fellow Hoosiers who, in less than a year, will be shut out of this lifesaving service. But my thoughts and prayers aren't going to help these individuals."

Indiana needs more leaders who understand the dire consequences their communities face. Political leaders need to make data-driven decisions, rather than be swayed by rampant misinformation. Interfaith leaders are among those who have been advocates for syringe services programs. Leadership requires proactive and inclusive decisions that prevent calamity and protect communities.

Scott County was at a crossroads in the community's HIV epidemic. While it lost its battle for a syringe services program, other regions shouldn't take this as permission to discontinue or to dismiss the lifesaving effects of syringe services. Cities, counties, and states that embrace these policies will be leaders in public health, promoting safer and healthier communities.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors are employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual authors and are not necessarily shared by their institution.