In a pivotal speech in his famous tragedy, William Shakespeare's Romeo asks, What's in a name?—a rhetorical question meant to suggest a thing is a thing and a person a person (Juliet) regardless of her last name and accident of birth.

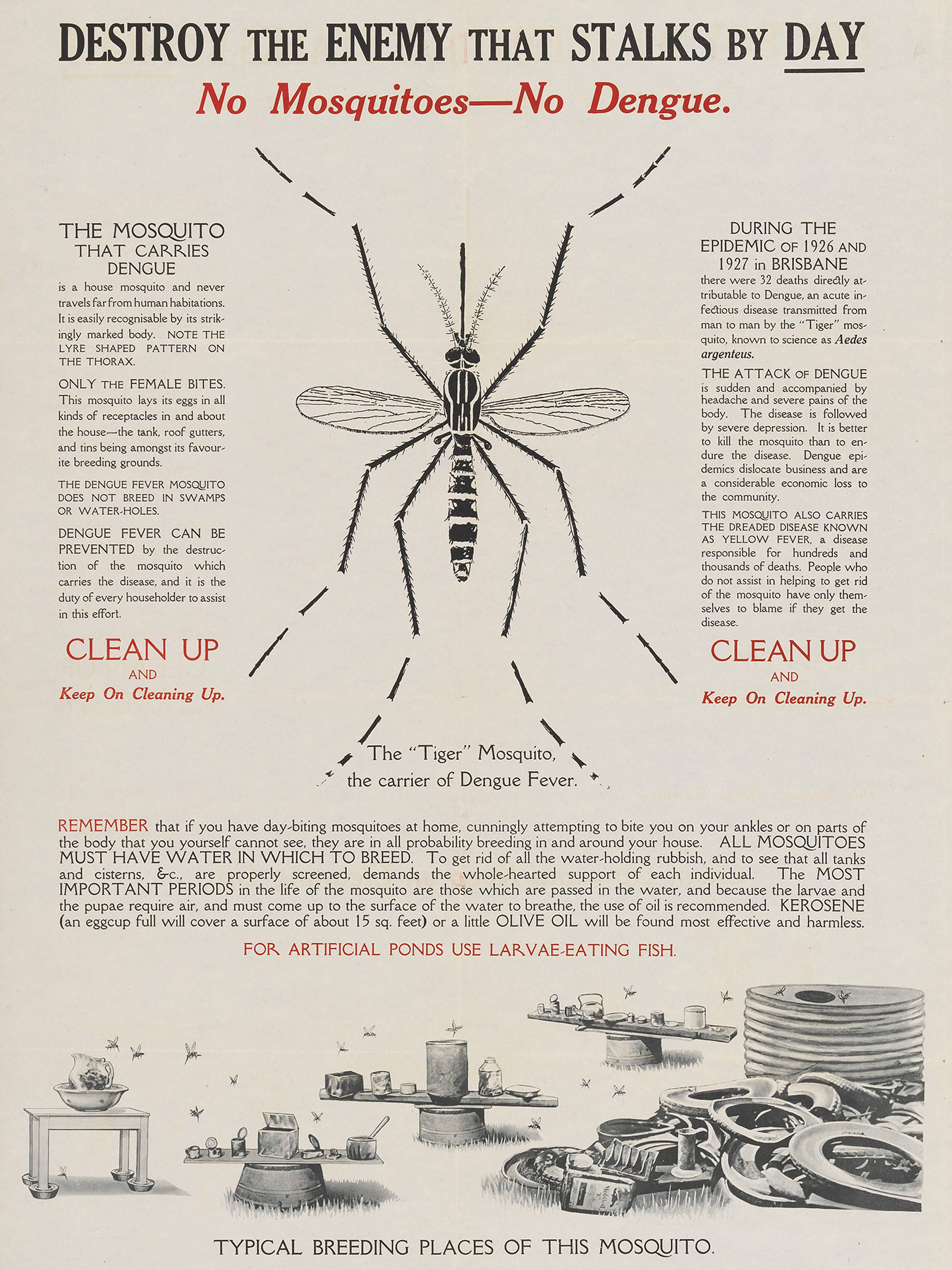

This week at Think Global Health, we ask the same question about dengue fever, the worldwide, mosquito-borne scourge that threatens billions, infects tens of millions, hospitalizes hundreds of thousands, and kills some 20,000 people around the globe each year. Indications are that dengue will become an even greater problem in the twenty-first century, especially in economically-disadvantaged areas.

But as common as it may be, a strange mystery surrounds the name "dengue," whose origins are forgotten. These are good theories of where the name comes from, and they suggest like most diseases it is named according to one of several old conventions.

Convention One: Named After its Discoverer

A few years before World War I, a German doctor attending a psychiatry conference in the city of Tubingen stepped up to the podium and described to his audience of fellow clinicians an unusual and puzzling case. For five years, he had treated a 50-year-old woman who suffered from paranoia, moodiness, aggression, disturbed sleep, and memory problems.

Alzheimer died with no clue the case would become a cultural touchstone and his name a household word

Her health became progressively worse during the five years, and after she died, he performed a post-mortem—dabbling as he did in neuroanatomy, which was all the rage in those days. He observed peculiar plaques and neurofiber tangles in her brain and pondered how her neurological problems could be related to them. Many at the meeting could not care less. Nobody at the time could have guessed this case and several others like it would anticipate one of the major age-related illnesses of our age—least of all the doctor, whose name was Alois Alzheimer. He died a few years later with no clue the case would become a cultural touchstone and his name a household word less than a century later.

Alzheimer was part of an old tradition, now largely abandoned in modern science, where diseases were named after the person who first discovered or described them. Another example stems from the work of George Huntington, a 22-year-old doctor on Long Island who described a progressive brain disorder he observed in East Hampton residents—a disease he called chorea, a Latin and Greek word (chorus or a group of dances), which we now call Huntington's disease.

Likewise, Parkinson's disease is named after James Parkinson, though he himself never called it that. Instead, he referred to the disease as "the shaking palsy," but it was later named after him in recognition of the fact he described several cases in a comprehensive 1817 study. Notably, there have been cases in which a disease was renamed to remove any association with its original discoverer, such as the rare vascular disease granulomatosis which was recently renamed polyangiitis to distance it from its discoverer, the doctor Friedrich Wegener, who was a member of the Nazi party.

Convention Two: Named After People Who Are Affected by It

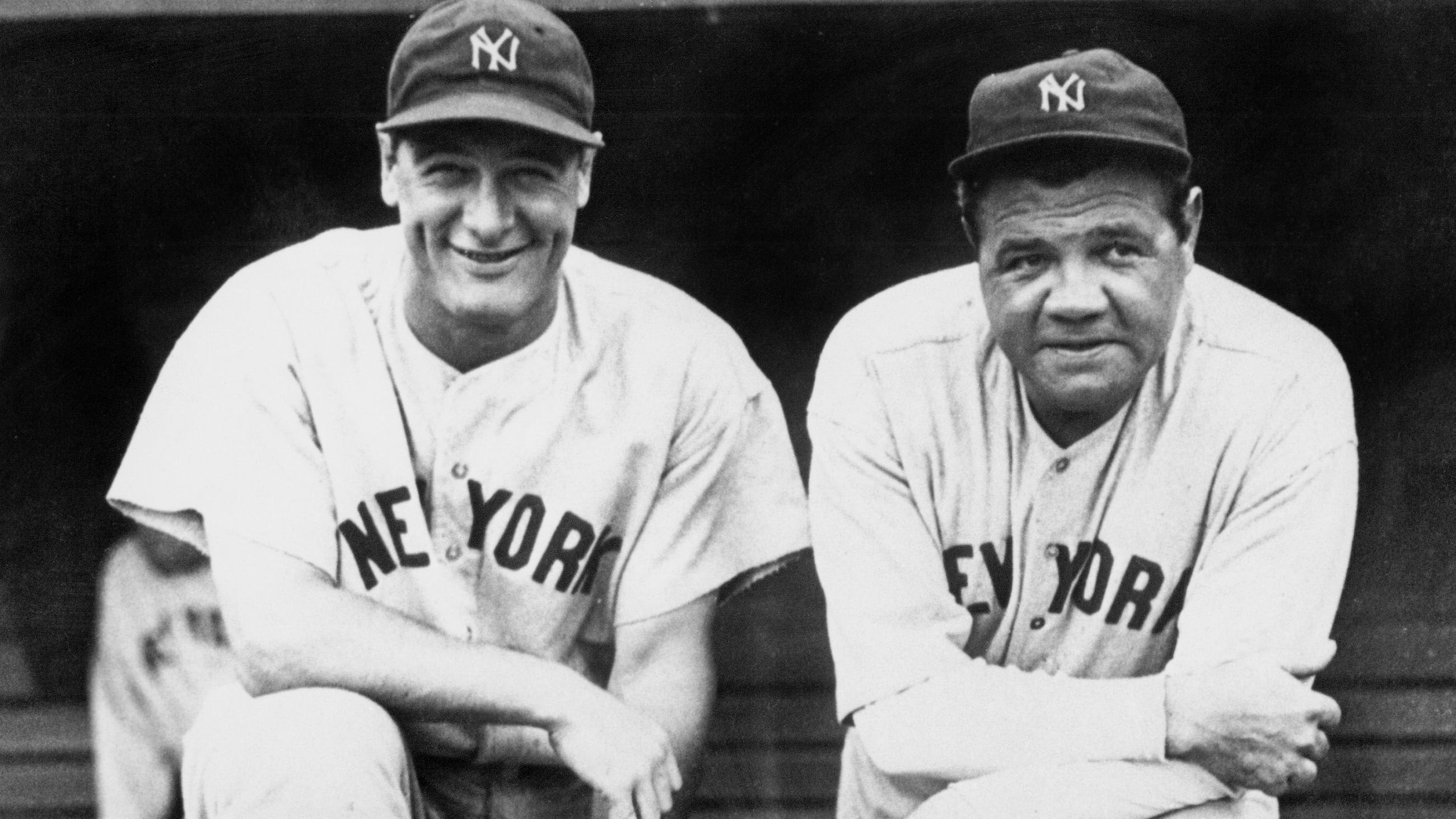

Some diseases are named after inflicted patients and susceptible populations rather than the doctors who treat them. The classic case of this is Lou Gehrig's disease, also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a name that recalls the iconic New York Yankees professional baseball player whose diagnosis with the disease cut short his storied career and forced him to quit after playing 2,130 consecutive games.

More common than naming diseases after an individual is naming them after a population—often an at-risk population that has become associated with that disease. One example is miner's lung, a form of pneumoconiosis associated with breathing in coal dust.

WHO recommends avoiding names of individuals, groups, and words that can be alarming or stigmatizing

Notably, the World Health Organization issued guidance in recent years spelling out best practices for naming infectious diseases, and they specifically recommend avoiding names of individuals, groups, and words that can be alarming or stigmatizing. One classic example is the name Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), the formal adoption of which effectively ended the use of names like gay-related immune deficiency (GRID), which had appeared in newspapers, as well as "gay plague," which was used early in the epidemic.

We are probably stuck with some of the legacy names, like Legionnaire's disease, which was coined in 1976 after 182 attendees of the 1976 American Legion conference in Philadelphia fell ill with an acute respiratory infection and 29 of them died. The culprit turned out to be a previously unidentified pathogen (the soon to be named Legionella bacteria), which spread through air ducts from a contaminated water tower at the convention hotel where they gathered. An early, competing name for the disease was associated with the place, not the people. Time magazine ran a cover story later that summer calling it, "The Philly Killer," which illustrates the third common way of naming diseases.

Convention Three: Named After Places

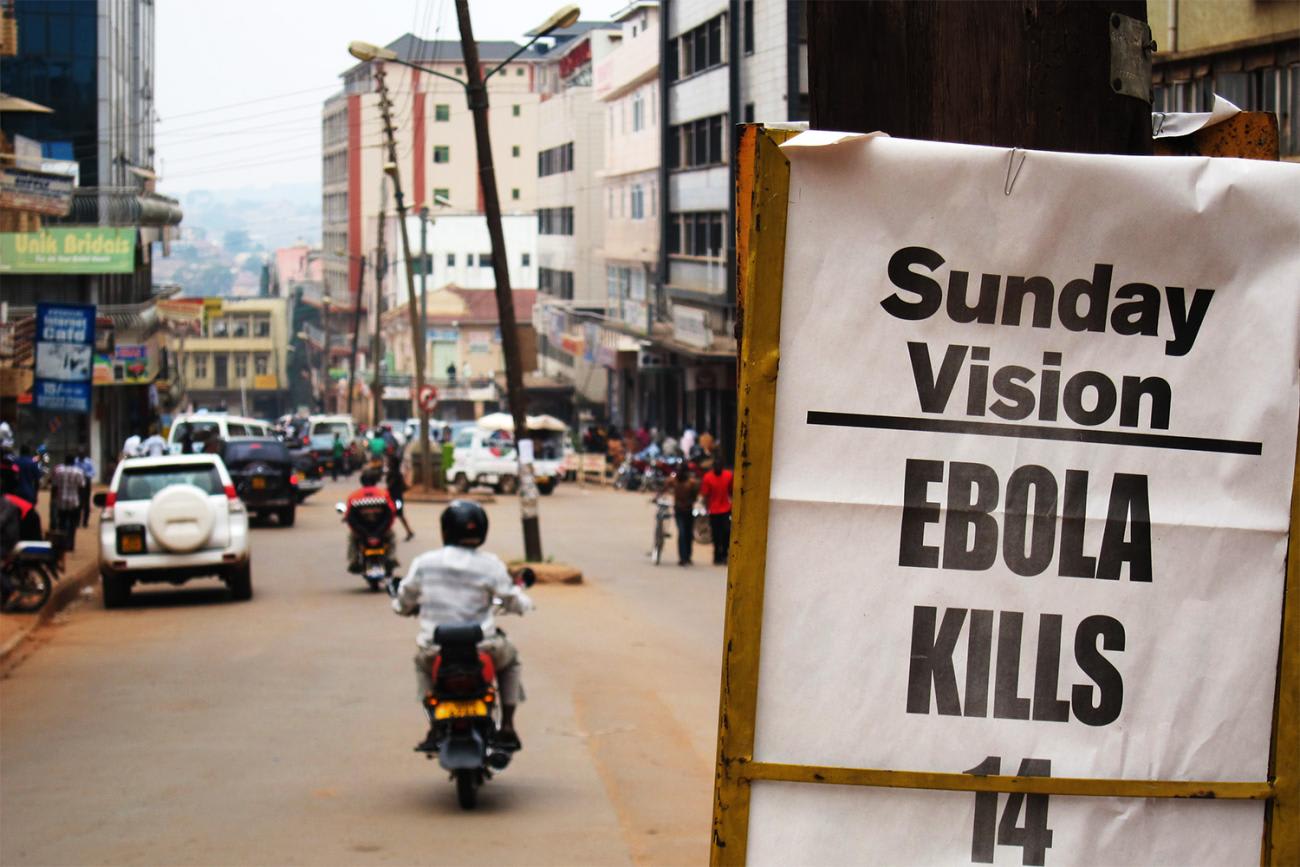

Diseases can be named after places as well as people. There's Ebola, the deadly viral hemorrhagic fever first discovered in the 1970s near the Ebola River in the modern-day Democratic Republic of Congo and named after that river. There's West Nile, identified in northern Uganda in the 1930s in a community on the western side of the Nile river. The disease Marburg fever, which is similar to Ebola, is also endemic to Africa but is named after the city of Marburg, Germany where several of the first reported cases occurred in 1967 after laboratory workers became infected by green monkeys imported from Uganda.

It's also worth including in this category the disease river blindness—named not after one particular river but many of them at once, owing to the fact that the black fly whose bite causes the parasitic disease breeds in fast-flowing streams.

Lyme disease is a rare combination of two naming conventions. It was brought to the attention of the medical community in the 1970s by doctors at Yale who were approached by two mothers from Old Lyme, Connecticut. And its causative agent, the spirochete bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, is named after Willy Burgdorfer, the scientist who first isolated it at Rocky Mountain Laboratories in the 1980s.

It was popular to blame syphilis on one's enemy—with whom one associated all manner of ills anyway.

There is a long history of syphilis being inappropriately named after places associated with one's adversary. This is likely because syphilis is a venereal disease and was highly stigmatized. Thus it was popular to pin it to one's enemy—with whom one associated all manner of ills anyway. Thus in Germany, Italy, and England, outbreaks of syphilis were called by the name "French disease." The Russians referred to it as "Polish disease." The Polish called it "German disease," The Danish called it "Spanish disease," and in the Ottoman Empire it was dubbed "Christian disease." In northern India, the Muslim and Hindu populations blamed each other for outbreaks of syphilis.

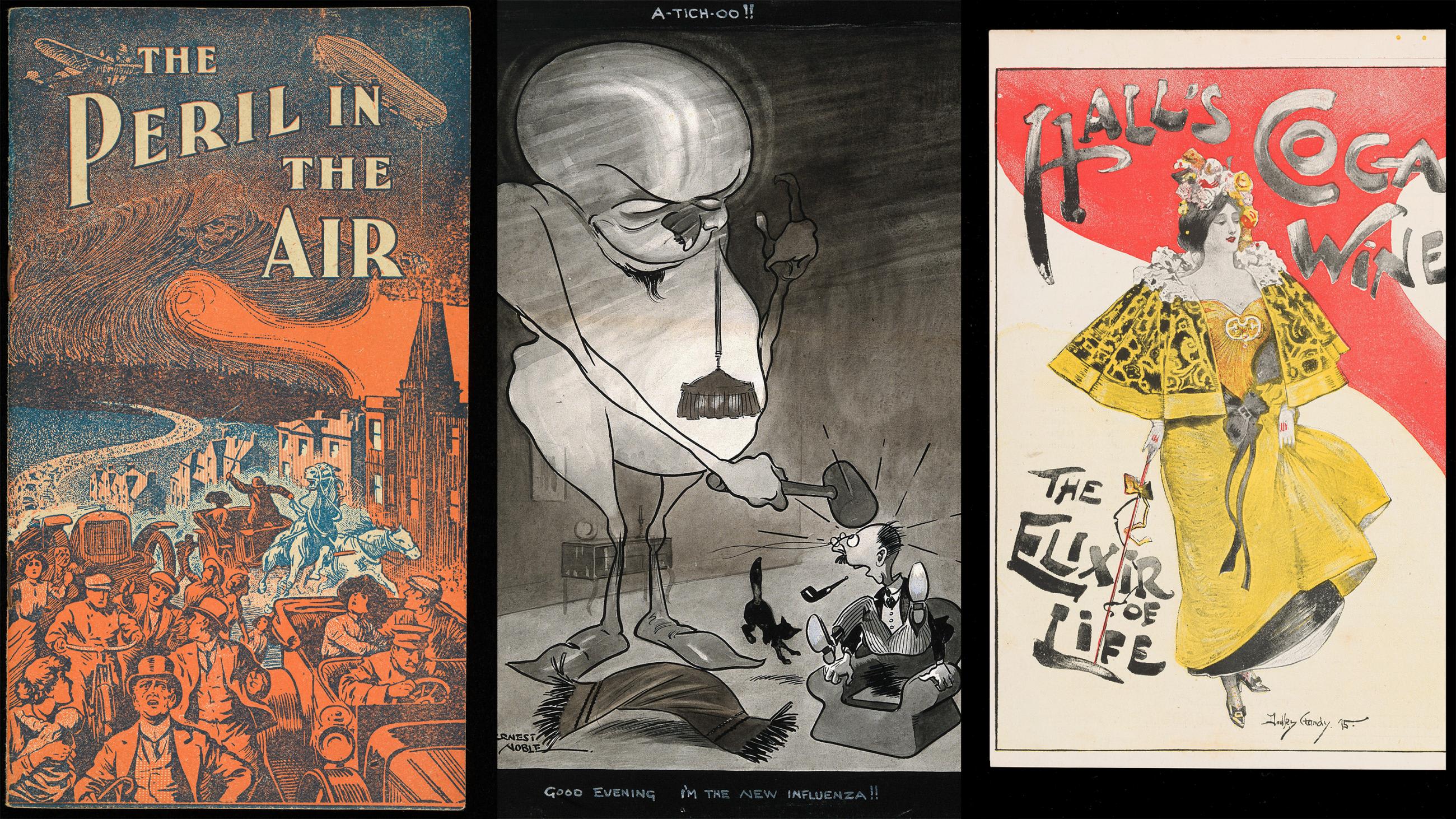

The disease Spanish flu was also informed by conflict, but in a slightly different way. Emerging in the dying days of World War I, Spanish flu is really just another form of influenza. But the virus had undergone a major "antigenic shift" into a form to which humans had no exposure and no immunity.

Influenza was widely covered by press in Spain after King Alfonso XIII fell ill with flu-like symptoms

This genetic change to the virus made it remarkable for its virulence, and before the 1918–1919 pandemic finally ended, Spanish flu had claimed more lives than the number of people killed in World War I. The reason why it was named "Spanish" flu was basically fake news. It did not originate in Spain, but because Spain was a neutral nation during the war, they did not have a censorship ban in place to prevent widespread reporting on the infection in the popular press. And the early days of the pandemic, it was widely covered by the press in Spain after King Alfonso XIII fell ill with flu-like symptoms in the spring of 1918. The irony? In Spain, the outbreak was referred to as "French flu."

Convention Four: Named for Their Appeance

Not every disease is named after a person, place, or thing. Many have names that enshrine their presentation, symptoms, or appearance—whether we understand the root cause of the disease or not. Chronic fatigue syndrome, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) are all various examples of diseases whose names almost capture a description of the disease itself. Others, like tonsillitis, meningitis, or heart disease, reflect the specific tissue or organ involved.

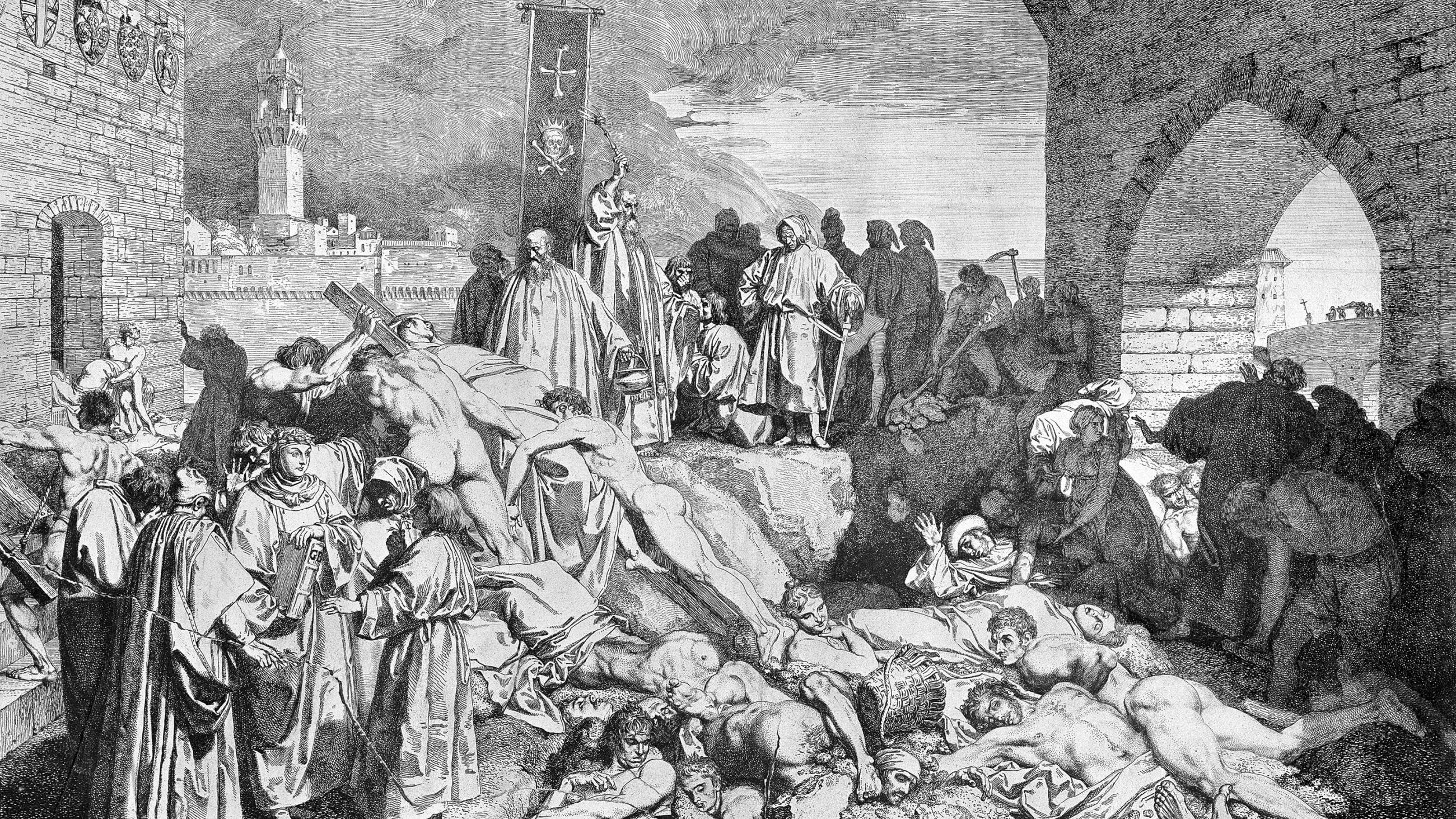

The name black death comes from the darkened tissue in people infected with Yersinia pestis bacteria

Some diseases are named purely for physical appearance. For instance, we owe the name yellow fever to its characteristic skin-discoloring jaundice, and the origins of the name black death come from the darkened tissue in people infected with Yersinia pestis bacteria. The most common form of Y.pestis infection, caused by an infected rat or flea bite, leads to swollen lymph nodes in the armpits, groin, or neck—something referred to in ancient times as buboes, which is where the name "bubonic plague" came from. Another example of naming a disease after its appearance is the autoimmune disease lupus, which was named by the Thirteenth-Century physician Rogerius Frugardi because of the characteristic red lesions that appear on the faces of people who have it. Lupus is Latin (wolf), though there is disagreement over whether Rogerius's intent was to signal that the rash was consistent with lesions you might see appearing on someone after a wolf's bite or whether he thought the rash itself gave people a wolf-like appearance.

Many diseases named after their appearance or defining symptoms have names that emerged in the ancient world. The name rabies is derived from one of two languages—either the Sanskrit Rabhas (to do violence) or the Latin Rabere (rage), both describing one its characteristic, antisocial feature.

Herpes—a name used by Hippocrates more than 2,000 years ago—is a Greek word that means "to creep"

Cancer is derived from the Greek word karkinos, ("crab"), apparently to evoke the general shape, stiffness, persistence, and sharp, crab-claw-like pincer pain of tumors wherever on the body they occurred. But as a modern social phenomenon, cancer is often focused on which organ is involved, and communities of cancer survivors, caregivers, and fundraisers often define themselves exclusively by that specific type of cancer. Other diseases have names that capture how they manifest. Herpes—a name used by Hippocrates more than 2,000 years ago—is a Greek word that means "to creep," which captures something of the way it spreads across the skin.

Convention Five: Named After a Thing

Lots of diseases are named after some living or inanimate thing associated with them—often in the most obvious way, like cat scratch fever, kidney stones, or mercury poisoning. Other times the name may be less specific but still associated with some physical thing—foodborne illness, for instance.

Sometimes these handles emerge before we really understand the disease at all. For instance, the name mad cow disease (also known as bovine spongiform encephalitis) was coined because of the erratic behavior of sick cows long before the development of the theory that the disease is caused by the aggregation of prion proteins in the brain.

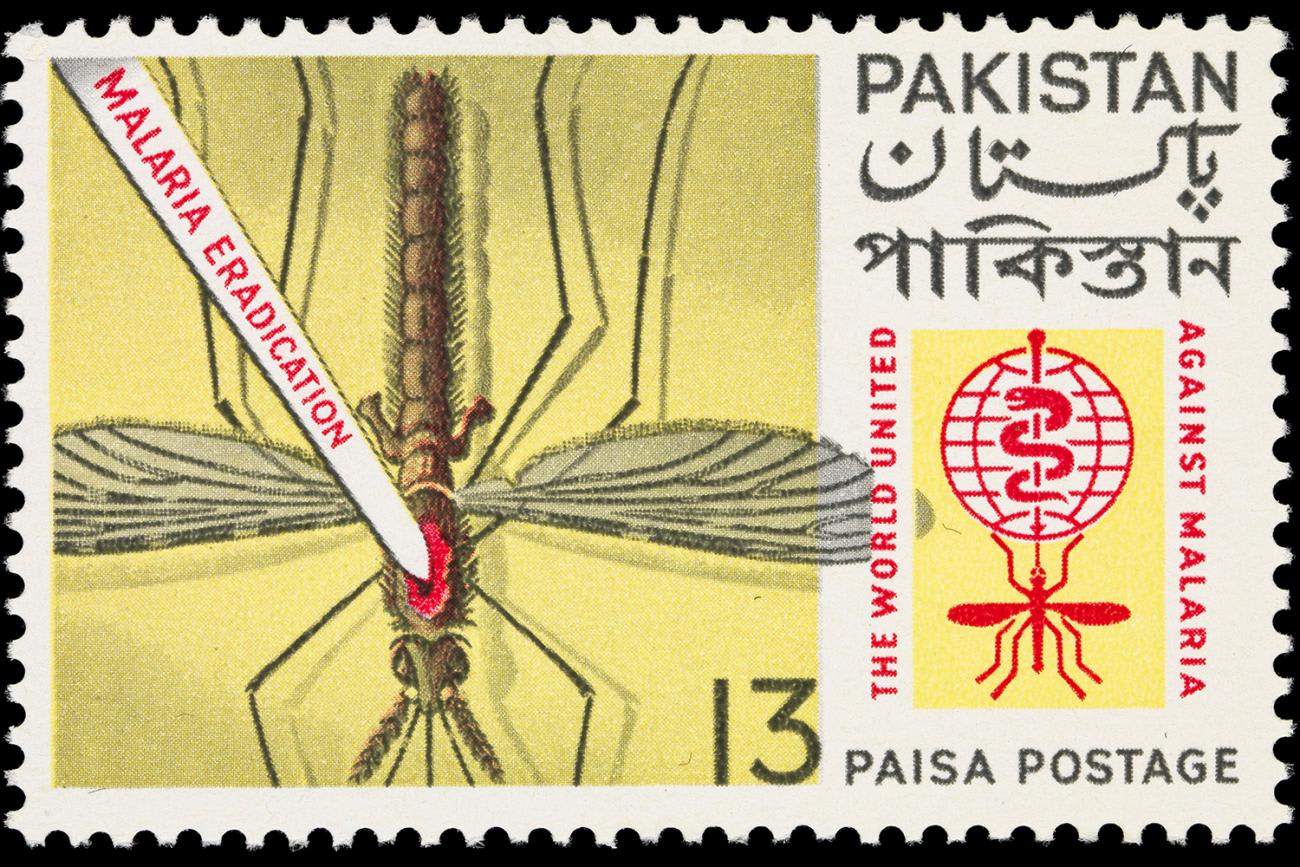

The name malaria has now been around so long, we may be stuck with it forever

Naming a disease after something before we really understand its central cause can lead to complete misnomers, and this has happened many times. One famous case is malaria, a name coined centuries before people understood it was in fact caused by a microscopic parasite transmitted from person to person by female mosquitoes. For thousands of years, people knew malaria was common to wet, swampy areas—hotspots for skeeters—but they assumed the disease was caused by nasty-smelling swamp gasses, which were believed in those days to directly cause They enshrined this misunderstanding in the portmanteau malaria, a mashup of two Italian words—(bad) and (air)—which to this day evokes an earlier, incorrect understanding of the disease. The name malaria has now been around so long that we may be stuck with it forever, but that's not always the case. Sometimes mislabeled diseases can effectively be renamed, as was the case with HIV/AIDS.

OK, But What About Dengue?

All this is to say most diseases are named for a reason—which may be right or wrong, but at least it's one we remember. Dengue fever seems to be the sole exception to this. Caused by a virus transmitted from person to person by mosquitoes, the origins of dengue's name are shrouded in mystery, though several theories do exist.

One possibility is that the word derives from the Swahili phrase, Ka-dinga pepo, which translates rather unelegantly into English (cramp-like seizure caused by an evil spirit). Another theory claims a European origin of the phrase. An early use of the phrase appears in a letter written in 1801 by Queen Luisa of Spain, who said herself that she was suffering from a bout of dengue fever, using a Spanish word (careful). Both explanations seem to indicate the disease is named after one of its visible symptoms, tender movements caused by the extreme pain one suffers from the muscle, bone, and joint inflammation.

It was called dandy fever in Barbados "from the stiffened forms and dread of motion in patients."

That would make sense, but there is a third possibility as well: that dengue is an old, Caribbean-island pidgin version of an English word (dandy). Massive outbreaks of the disease struck Cuba and Barbados in the early 1800s, before jumping to New Orleans, and one account given by a doctor at the time claims it was called dandy fever in Barbados "from the stiffened forms and dread of motion in patients."

Now, reaching the end of this essay, you may find yourself asking, why does any of this matter? That's basically the same question Shakespeare asked through Romeo's speech and question, "What's in a name?" It's not that the name matters so much as the fact that a third of the world's people live in areas where dengue is endemic. It doesn't matter what we call it—those people are at risk of infection. Dengue matters because the number of people it threatens is expected to grow, fueled by the forces of climate change, urbanization, and poverty. The old name may not matter, but the future human suffering and deaths do.

What's in a name? A thorn by any other name would remain as sharp.