Medical illustrations help train health-care professionals to recognize illnesses and conditions. However, only 4.5% of images portray dark skin, according to a 2018 study that examined more than 4,000 images across major medical textbooks. Although it's crucial for clinicians to identify conditions in diverse skin tones, people of color's (POC) experiences and needs are often overlooked, leading to misdiagnosis.

Representation in medical illustration is vital for relatability and diversity in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, according to academics, clinicians, scientists, and illustrators of color. The field, with approximately 2,000 practicing illustrators globally, is evolving because of increased awareness of diversity and advances in science and technology. In the few cases when POC are depicted, they're often in negative contexts, such as sexually transmitted infection.

Think Global Health sat down with medical illustrators Ni-ka Ford, founder of Enlight Visuals; Sana Khan, founder of Sfkhanvisuals; and Juno Shemano, founder of Juno Xi Studios , to discuss their paths into the profession along with the importance of accurate representation in medical illustration.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: How did you become a medical illustrator?

Ford: I've been an artist my whole life. I attended Georgia Southern University for fine art and became enamored with science my senior year. I had no idea how to pursue science, so I'd look at histology and anatomy books for fun in the library, which inspired my paintings.

I created a body of work that compared human anatomy with nature, highlighting the similarities and connections we have between our bodies and nature. One of my illustration teachers saw the work I created and told me about the field.

After taking time between undergrad and grad school to get the science prerequisites, I eventually earned a master's in biomedical visualization from the University of Illinois Chicago in 2017, which launched me into the profession.

Shemano: In high school, I was split between pursuing a scientific or artistic career. I knew I wanted to combine them but wasn't sure how until my guidance counselor pulled me aside to meet a medical illustrator who told me about his career.

I attended Rochester Institute of Technology, where I earned a bachelor of fine arts with a minor in cellular and molecular biology, which led to my enrolling at the University of Toronto for medical illustration.

Khan: It was by accident! I completed my undergraduate degree in neurobiology genetics and behavior and thought the natural next step was to continue research in this field with either a research-based master of science or doctorate.

I came across a National Post article discussing the field of medical illustration and became interested because it allowed me to blend my artistic skills with a deep interest in science and medicine.

Think Global Health: The world has a population of more than 8 billion people, representing many races and ethnicities. Yet when you look at medical illustrations, it's mainly white men, which doesn't accurately represent the global population. Why is it important we see more representation in medical illustrations?

Ford: This has been a major focus of my work since grad school.

I specifically noticed working in medical education that the first and second year students were complaining about the lack of diversity in their lecture slides and teaching materials, which is significant for numerous reasons.

Lack of representation contributes to unequal health-care experiences and outcomes for POC

My department focused on improving diverse representation by working with faculty.

If physicians, medical students, and health-care professionals are not exposed to people of different backgrounds, body shapes, and ethnicities, then they're not going to know how to identify specific conditions or appropriately engage with those patients in the clinic.

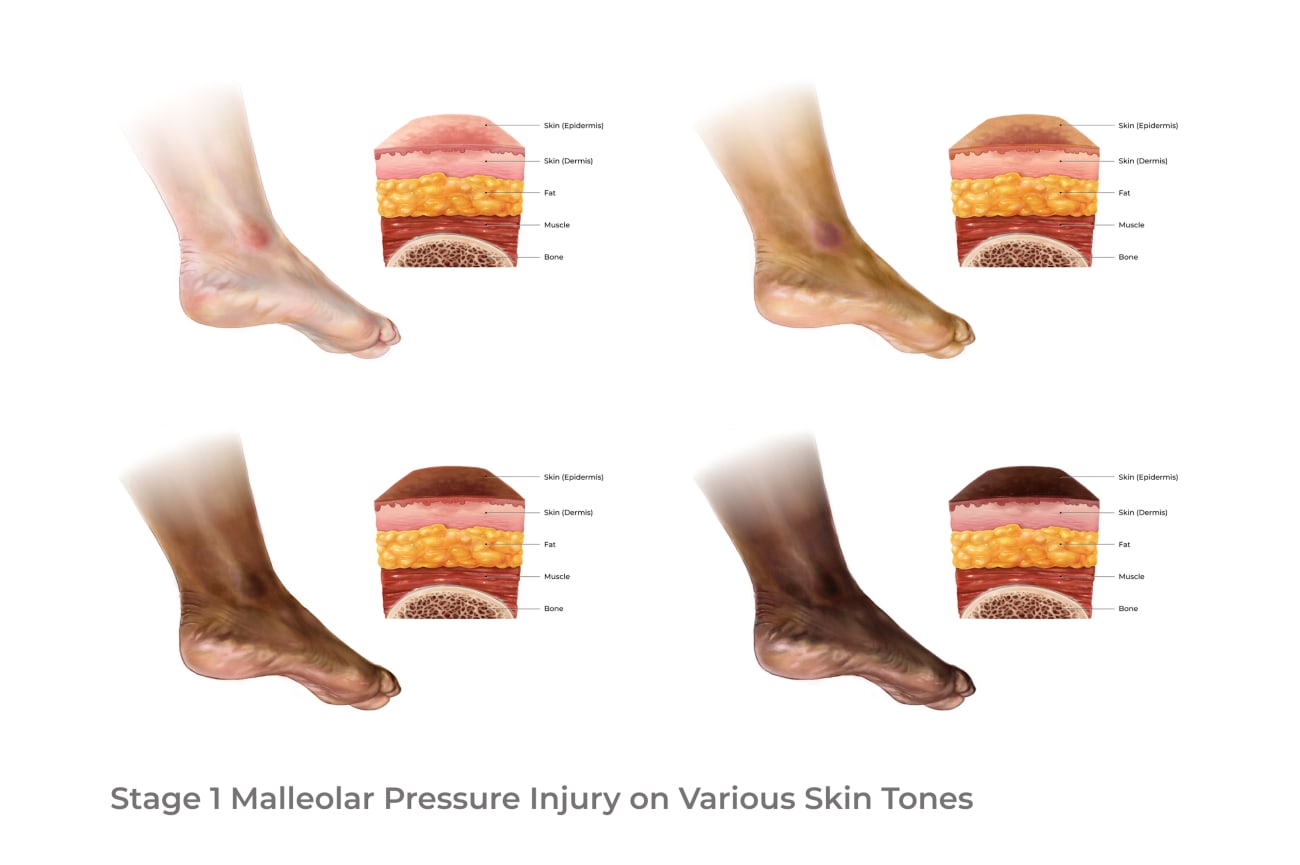

When it comes to dermatology, there's a huge lack of resources, photography, and illustrations. That can be detrimental to a patient's health and can lead to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis if you don't know how to identify [conditions] on dark skin. If you're in a doctor's office and you don't see illustrations or patient pamphlets where the people in the illustrations and materials resemble you, it can lead to a bit of mistrust. It's something that's starting to change, but there's still more work to do.

Khan: Diverse representation can improve patient care by fostering inclusivity, helping health-care providers recognize how conditions manifest differently across skin tones and body types, and reducing health disparities. Furthermore, it promotes trust and understanding in health care because patients are more likely to engage with materials that reflect their identity.

Think Global Health: What are some of the health implications that the lack of representation in medical illustrations can have on people of color in terms of self-diagnosis, clinical diagnosis, or even building trust within like the health-care system in general?

Ford: If you can't find resources or anything online of people that resemble you, with the condition you have, then you won't know how to recognize it on yourself.

Someone who has darker skin may have more trouble trying to find [an image of a disease] that looks similar to how it's represented on their body.

So, I really like that you mentioned self-diagnosis because I don't think that's talked about enough because that's your starting point to know, "OK, this is what I need to go do."

In regard to building trust with the health-care system, my view as someone of African American descent is that trust has been broken in the Black community with the health-care system since slavery essentially.

The generational implications of that have caused Black people to mistrust the medical system because of medical apartheid and injustices committed back then.

That's something that has to be rebuilt, which takes a long time.

Khan: The lack of representation in medical illustrations can have significant health implications for POC, leading to misdiagnosis, delayed treatment and health disparities. Medical conditions often manifest differently on darker skin—for example, redness or erythema can actually show up as a deep purple or violet instead of the reddish and pink hue characteristic on lighter skin tones. When illustrations predominantly show white skin, health-care providers may not be equipped to recognize symptoms in POC, which can result in improper care and worsen outcomes. Overall, this lack of representation contributes to unequal health-care experiences and outcomes for POC.

Certain diseases affect specific racial or ethnic groups uniquely, such as vitiligo, sickle cell anemia, and melanoma, and their representation on different skin tones can cause confusion and reinforce stereotypes. Rushed illustrations could miss how conditions vary by skin tone, such as the absence of a classic bullseye rash in darker-skinned individuals with Lyme disease, which affects diagnostic accuracy.

Think Global Health: Do you see certain illnesses or diseases that are usually stereotyped with a specific group of people in medical illustrations?

Khan: I have often come across illustrations online that associate specific illnesses with POC. For example, sickle cell disease is frequently depicted as affecting only Black individuals, even though it also affects other ethnic and racial groups. Conditions such as diabetes and obesity are disproportionately shown in Black and Hispanic populations, reinforcing harmful stereotypes.

Substance abuse and mental health issues are also sometimes linked to POC in medical depictions. In my research for the J&J diversity fellowship, I came across numerous illustrations of dermatological conditions that were mostly illustrated on white skin, contributing to the misconception that these issues don't affect people with darker skin, leading to misdiagnosis and inadequate care.

Think Global Health: Where do you see the future of medical illustration going?

Ford: The cool thing about medical illustration is that it evolves with technology. As advancements like virtual reality and augmented reality emerge, illustrators adapt, ensuring a continuous evolution—which is the most exciting part about this field.

In terms of diversity, I definitely see that improving in our field.

It has been talked about more over the past 5 to 10 years, and it's only going to evolve and get better.

Our field is trending in the right direction when it comes to being more inclusive. Even though only 8% [of medical illustrators are people of color], about five years ago, it was more like 2%.

Shemano: We're going to start to have more patient-specific virtual simulations or even just health care, and that's really great to see because health care isn't fit one size fits all.

We're also really pushing for more diversity within the field, not only the creators, but also the work that is coming out.

Khan: I agree that the future of medical illustration will grow with science, communication, and technology. Demand for clear visual communication is rising with the evolution of research and health care. Innovations such as 3D modeling and [artificial intelligence] AI-assisted design will enhance conveying complex medical information, bridging gaps for better understanding.

However, traditional medical illustration techniques, prized for their artistry and personal touch, will endure alongside digital tools. Their unique aesthetic and human connection will persist, vital for fostering empathy and trust in health care.

Their unique aesthetic and human connection will persist, vital for fostering empathy and trust in health care

However, traditional medical illustration techniques, prized for their artistry and personal touch, will endure alongside digital tools. Their unique aesthetic and human connection will persist, vital for fostering empathy and trust in health care.

Think Global Health: What advice would you give someone who's coming into or thinking about pursuing this field?

Ford: Definitely mentorship. That's my number one piece of advice. Mentorship helped me so much, especially as a new student in the field. Having a mentor after you graduate is helpful as well.

Almost all people in our field are open to giving advice.

I'd also recommend figuring out what part of science or anatomy really interests you because that's something that you can start pursuing early.

For example, when I noticed that I really love just learning about the brain and illustrating it, I started to get more clients that would come to me, such as neurosurgeons or neuroscientists, wanting illustrations of the brain for publication.

Shemano: Connecting with your professors and your classmates is so important.

We all come from a background of being excited about science and art, but there are so many diverse people within the field and getting their perspectives is really important. It's great to connect with your classmates and form these bonds early on, hopefully creating lifelong connections.

I'd recommend specializing, but as Ni-ka said, think about what excites you. There are so many avenues within medical illustration that I wasn't even aware of, even knowing about it in high school.

So, connect with others, explore interests within the field, and have fun!

Khan: For aspiring medical illustrators, I'd advise focusing on mastering art skills and scientific knowledge, which are vital to accurately depicting anatomy, physiology, and medical science. Schools provide this training, but early preparation is beneficial!

I also recommend prospective medical illustrators build a diverse portfolio showcasing their ability to represent different medical concepts, styles, and populations, particularly because diversity in illustration is increasingly important. As Ni-ka and Juno mentioned, networking within the medical and art communities, attending conferences, and connecting with professionals via social media are all excellent ways to gain insights and opportunities.

Last, adaptability is key—keeping up with evolving tools such as 3D modeling, animation, and possibly AI, while also maintaining a respect for traditional techniques like carbon dust and graphite pencil.