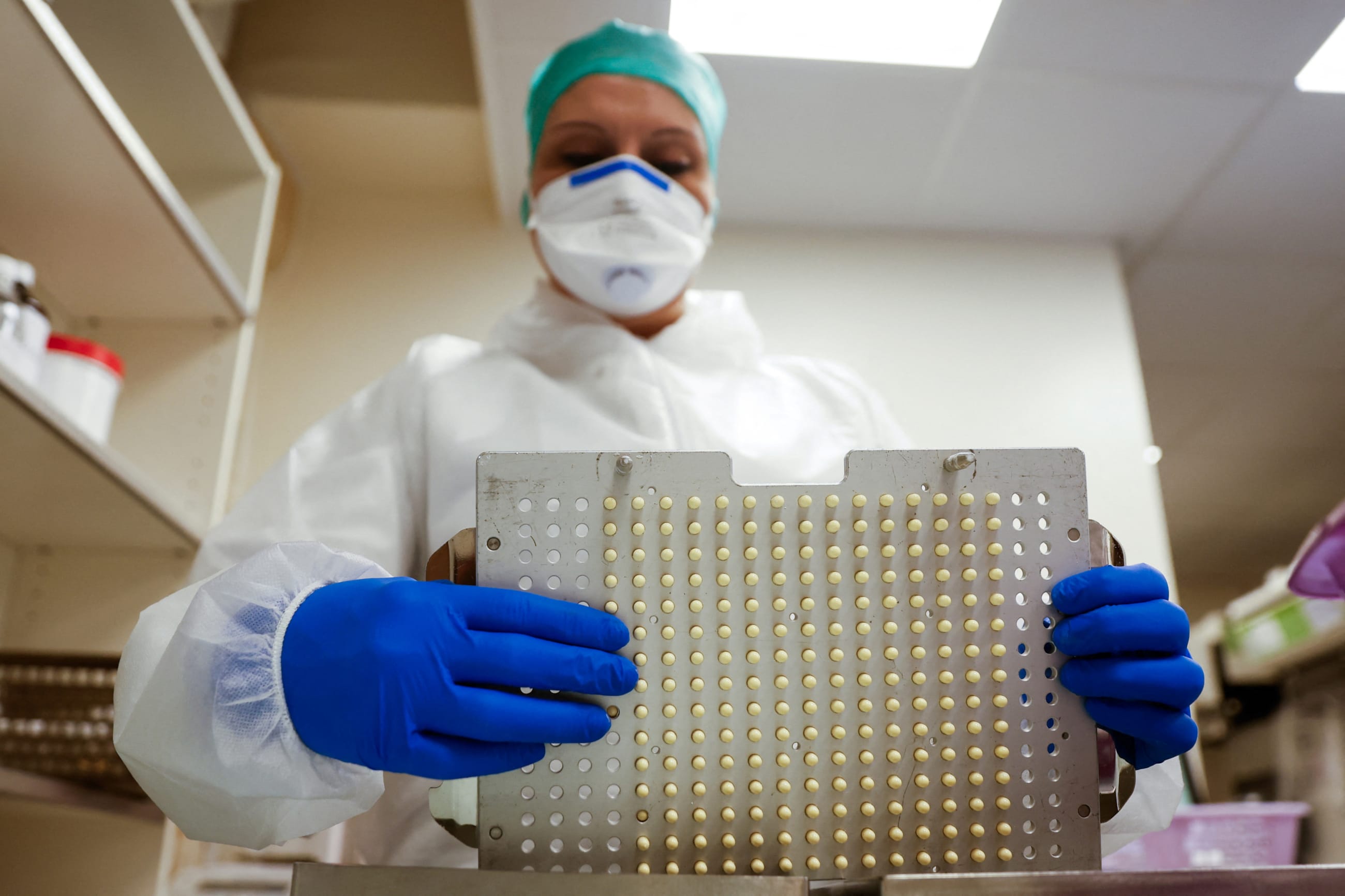

Syphilis rates have been rising in the United States for 10 years. If untreated, the disease poses grim risks, from heart and brain damage to blindness to miscarriage and infant death. Yet when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced a shortage of benzathine penicillin G—the only approved treatment for pregnant women—in 2023, the agency waited nine months before importing a version of the drug from a French pharmaceutical company approved for use in Europe.

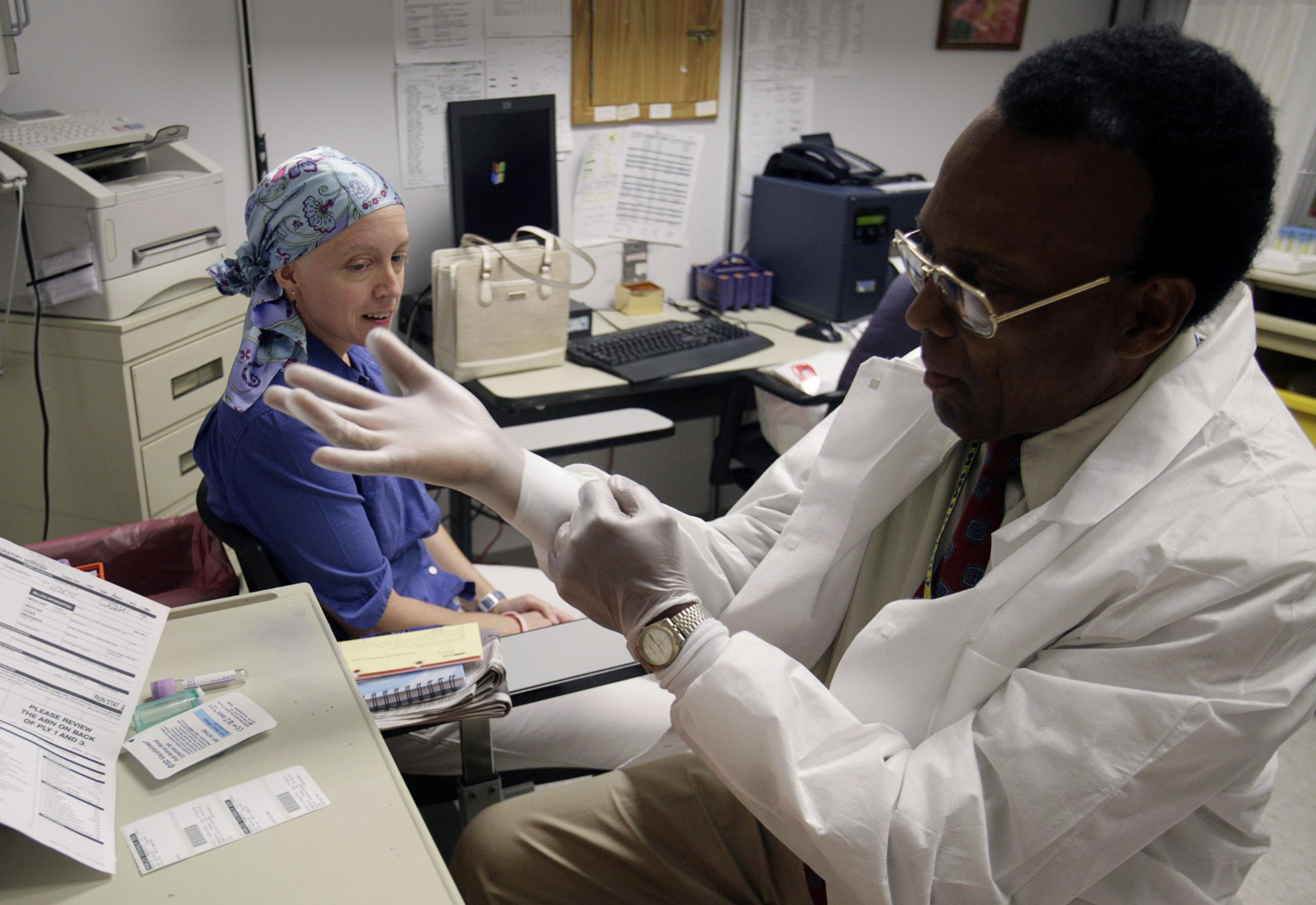

This story is hardly unique. U.S. drug shortages hit a record high last year. A shortage of the popular chemotherapy drug cisplatin forced cancer centers to ration their use of the treatment to stage 4 cancer patients before the FDA authorized a foreign-approved substitute.

Both the outgoing Joe Biden administration and incoming Donald Trump administration promised to prioritize reducing U.S. drug shortages. Nevertheless, progress has been slow because many of the proposed solutions, including increasing generic drug manufacturing, require congressional action and could result in raising already high prescription drug prices.

The New England Journal of Medicine recently published a study by the Council on Foreign Relations and Harvard Medical School that suggests an alternative approach: enabling the FDA to more readily authorize the importation of critical generic drugs from well-regulated foreign markets to prevent and resolve shortages, thereby strengthening U.S. supply chain resilience.

Although U.S. drug shortages have persisted for decades, some are more predictable than others. More than half the record-high number of active shortages in 2024 involved generic sterile injectable medicines: drugs such as epinephrine and morphine that have been around for years and are staples of hospital care. Part of the explanation is that low margins and quality-control challenges for these medicines have reportedly driven many U.S. manufacturers out of the market. The cost and time required for FDA approval can limit the number of new entrants responding to surges in demand, and, once U.S. drug shortages occur, they tend to last three years on average.

To ease shortages, the U.S. secretary of health and human services already has the authority to allow temporary importation of foreign versions of medicines on the FDA shortages list when U.S. "demand or prospective demand" exceeds supply. The FDA purports to only rarely exercise this authority, but the study found increasing instances—at least 21 since 2017— for just generic sterile injectables in shortage alone. The problem is that authorization is generally a last resort and comes only after months or years of delay, leading to higher health-care costs and unnecessary patient harm.

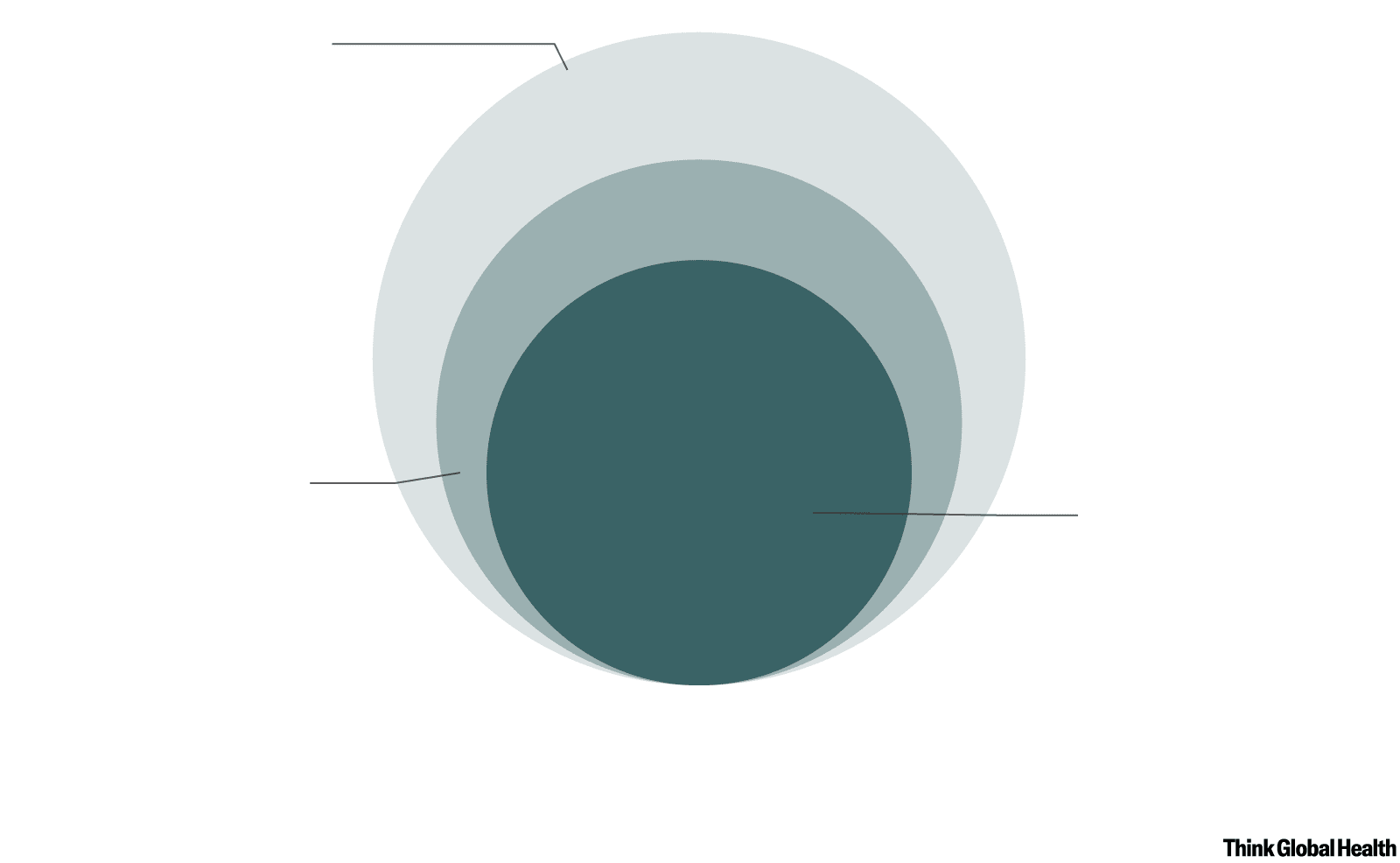

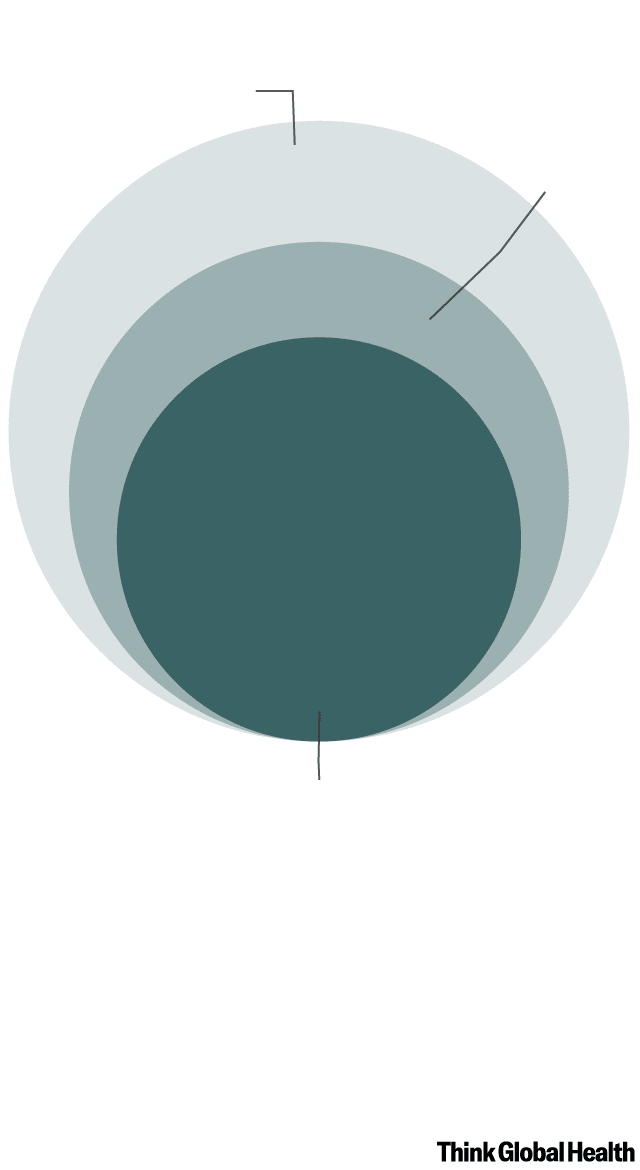

Using public databases from six markets determined well-regulated by study authors—Australia, Canada, France, Germany, New Zealand, and United Kingdom—the New England Journal of Medicine study estimates that for two-thirds of generic sterile injectable drugs in shortage between 2021 and 2024, at least one manufacturer developed a version approved for distribution in at least one of those peer countries but not in the United States.

According to the study, 125 sterile injectables appeared on the FDA shortage list between 2021 and 2024, 81 were produced by three or fewer U.S. manufacturers, known as "study drugs"—a threshold that the FDA and analysts use to identify generic drugs with inadequate competition—and 53 had at least one approved version available in other well-regulated markets.

Opportunities for Drug Importation

More than one-third of generic sterile injectable drugs in shortage in the United States are also manufactured in other countries with well-regulated drug markets

All off-patent sterile

injectible drugs (125)

Identified from the FDA

shortage list between

2021 and 2024

Study drugs (81)

Study drugs with

importable equivalents (53)

Off-patent sterile

injectable drugs with

fewer than three U.S.

manufacturers and

approved by FDA

Study drugs with more than

one manufacturer approved

in one or more of six other

well-regulated drug markets,

but not approved by FDA

FDA = Food and Drug Administration. Some study drugs might have other FDA-approved dosages, which could be used in case of a

shortage, although directly substitutable versions would be clinically preferable.

Chart: CFR/Allison Krugman • Source: New England Journal of Medicine

All off-patent sterile

injectible drugs (125)

Study

drugs (81)

Study drugs with

importable equivalents (53)

FDA = Food and Drug Administration. Some study drugs

might have other FDA-approved dosages, which could

be used in case of a shortage, although directly

substitutable versions would be clinically preferable.

Chart: CFR/Allison Krugman

Source: New England Journal

of Medicine

The FDA already has protocols in place for risk-based assessment of importation candidates and the quality and safety of the relevant manufacturing facilities. It indicates any differences between the domestic and foreign products to health-care providers and posts them online.

Because drug shortages are often restricted to an individual country, importation from trusted partner countries is feasible. A 2022 study of drug shortages in Finland, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the United States showed that 41% of U.S. shortages affected only the United States, and only 1% of the 99 shortages studied affected all five countries. Because importation of foreign versions of U.S. approved drugs occurs only in times of shortage, the risk to long-term U.S. manufacturing is limited. The FDA already determines in advance the quality and volume of medicines to be imported and takes measures to enable importing manufacturers to plan for production needs, which can alleviate concerns about supply disruptions in their home markets.

Still, as a matter of policy, the FDA—which considers its own approved products to be lower risk—pursues this option only after exhausting every other option for boosting supplies. The study authors argue that theoretical risks posed by importing a version of a generic drug that has been on the U.S. market for decades and deemed safe by a stringent national regulator in a country such as the United Kingdom or Germany should be weighed against the real harms to patients, hospitals, and clinics of a critical medicine shortage.

Importation cannot address all the causes of the United States' stubborn drug-shortage problem. Long-term solutions will require both congressional action and overcoming opposition to any resulting increases in prescription-drug costs for taxpayers, hospitals, or patients. But importation is a useful option that should be deployed more effectively while longer-term solutions for reliable, resilient generic drug production are pursued. The FDA could begin scoping out and assessing potential foreign sources of critical drugs that two or fewer U.S. manufacturers produce and be prepared to issue importation orders as soon as a drug is added to its shortages list. Manufacturers could help by updating their drug-shortage risk management plans, as required by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, signed into law in July 2020. They could identify potential alternative foreign suppliers, including their own subsidiaries that produce the drug for other well-regulated markets.

Life-saving generic injectable drugs, such as chemotherapy for cancer patients or penicillin G to keep mothers' pregnancies safe, should not be making headlines for delayed access in 2025. Patients should not have to and need not wait so long.

*This text has been adapted from "The Role of Importation in Remediating U.S. Generic Drug Shortages" in the New England Journal of Medicine by Thomas J. Bollyky, JD, Sarosh N. Nagar, BA, Chloe Searchinger, BA, and Aaron S. Kesselheim, MD, JD, MPH.