Last year, international attention briefly turned to a lab in Botswana, where scientists first identified the omicron COVID-19 variant and sounded the alarm for the rest of the world. Led by Sikhulile Moyo, the laboratory director at the Botswana-Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership (BHP) lab, the team of scientists that made the discovery were looking for mutations as part of their thoughtfully designed genomic surveillance plan. The media—and the pandemic—have moved on from the discovery of omicron, but the story of the BHP lab deserves a closer look.

As a former U.S. Ambassador to Botswana, I have spent a great deal of time thinking about how forging partnerships with stable, well-governed African states can deliver meaningful progress on problems of mutual concern and help frame global problems in a different, often illuminating, perspective. The collaboration between Botswana and Harvard that created BHP is a powerful example of what is possible, and how seeds planted in one context can develop into institutions with far more to offer than initially imagined.

For years, the BHP lab has been quietly modeling the value of prioritizing human capital development and regional capacity, as well as correcting lazy thinking that imagines scientific best practices flowing in only one direction. As policymakers grapple with the global health inequities exposed by the pandemic, and rethink everything from global pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity to surveillance strategies, the BHP lab provides insights into the benefits of investing in African capacity and paying close attention to Africa's health priorities.

BHP is a powerful example of how seeds planted in one context can develop into institutions with far more to offer than initially imagined

In 1996, Botswana's Ministry of Health and the Harvard School of Public Health formed a partnership aimed at combating the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which was accelerating in southern Africa at a terrifying speed. That collaboration was just one element of a comprehensive national response, in which Botswana became the first country in Africa to offer antiretroviral drugs to its entire population. As part of the Botswana-Harvard partnership, a research lab was established in the capital city of Gaborone by the end of 2001. The initiative evolved, and the BHP became a fully autonomous entity, incorporated in Botswana since 2007.

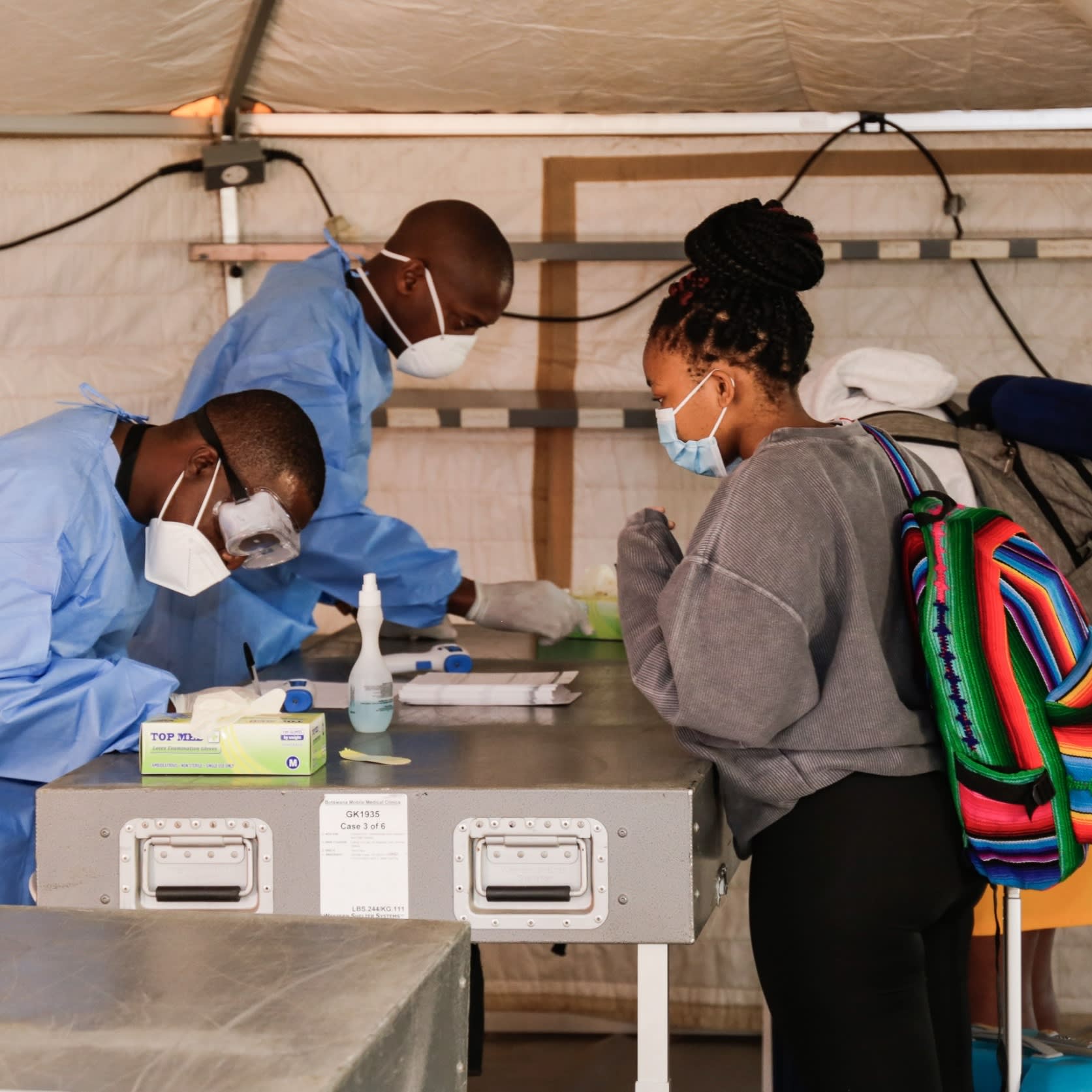

Botswana could seem an unlikely host for cutting-edge medical research; the country did not boast a medical school of its own until 2009. But its pioneering public health response to HIV helped to create a context in which national leadership has prioritized health, welcomed thoughtful collaborations, and has developed strong legal and normative frameworks around the ethics of public health research. BHP has produced groundbreaking work that has improved health outcomes around the world, perhaps most notably in the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Results from studies conducted at BHP changed treatment and public health guidelines written by the World Health Organization and UNAIDS. Early warning about omicron happened because decades of HIV-related work in Botswana honed expertise and built infrastructure around infectious disease surveillance and molecular diagnostics, which BHP quickly adapted to address COVID-19.

The lab in Gaborone is now a scientific center of excellence. Its leaders have prioritized training local and regional scientists, developing talented professionals who have gone on to major leadership positions in their fields. And the lab itself has become an important node in a network of African research institutions that advance health science and policy around the world. Moreover, because Africans are in the driver's seat, their ambitions reflect the preoccupations of the region.

Because Africans are in the driver's seat, their ambitions reflect the preoccupations of the region

Today, BHP leaders are eager to dive into research around the intersection between climate change and health. They are asking questions, for example, about pathogen mobility in extremely dry climates, a sensible agenda for a country dominated by the Kalahari Desert and coping with more extreme and more frequent droughts. BHP leadership also wants to strengthen the lab's bioinformatics capacity while shaping norms around data ownership and sharing—a priority informed by the region's bitter experience of being subjects of research conducted without any local say in the defining of rights and responsibilities.

It is easy to see the value that BHP's research efforts could generate far beyond Botswana's borders. Paying attention to the science being pursued at institutions like BHP can also help U.S. policymakers refresh their thinking about global health priorities. While HIV remains an important and expensive public health challenge in southern Africa, it does not dominate the regional public health agenda the same way that it dominates U.S. global health budgets. BHP's scope of research now extends far beyond HIV, anticipating the health challenges confronting the next generation. To be a relevant and valued partner, the United States needs to understand the over-the-horizon concerns of Africa's scientific and public health communities, and to recognize that their progress and insights improve the health outlook for everyone.