Back in July, a video went viral. It’s a short clip of a man on a train offering a young woman his seat. At first, it does not look remarkable. But upon watching the video again, an all-too-common story snaps into place. Another man, sitting down, was using his phone to subtly take photos of the women, trying to slip the camera under her skirt. The bystander brushed past him, knocking the man’s phone away, as he offered the woman a chance to sit down—and some privacy.

It's a positive message: when you see harassment, do something about it.

But that shouldn’t be the only message inspired by videos like this one. Harassment, assault, and other affronts to women’s safety on public transportation are not about individuals or one-time instances. It’s a systemic problem, and the solutions must be equally wide-ranging, too. Active bystanders are one piece of the solution, but when 48 percent of experts across twenty-two cities on six continents say it’s either extremely unsafe or unsafe for girls to use public transport after dark, cities planners should find additional ways forward.

experts who say it's unsafe for girls at night

Progress on the issue of harassment on public transport is especially important because women are a critical part of countries’ economies, but women can’t contribute to the GDP if they can’t get to work. Based on figures from the McKinsey Global Institute, Rusha Sen calculated that $2.9 trillion could be added to the annual GDP of India alone by 2025 if women had an equal role in the labor force. However, the urban workforce participation rate for women in India is still about half of that of men, which is partly because of pervasive harassment that women face. When unsafe transportation prevents women from accessing city centers, everyone is poorer for it.

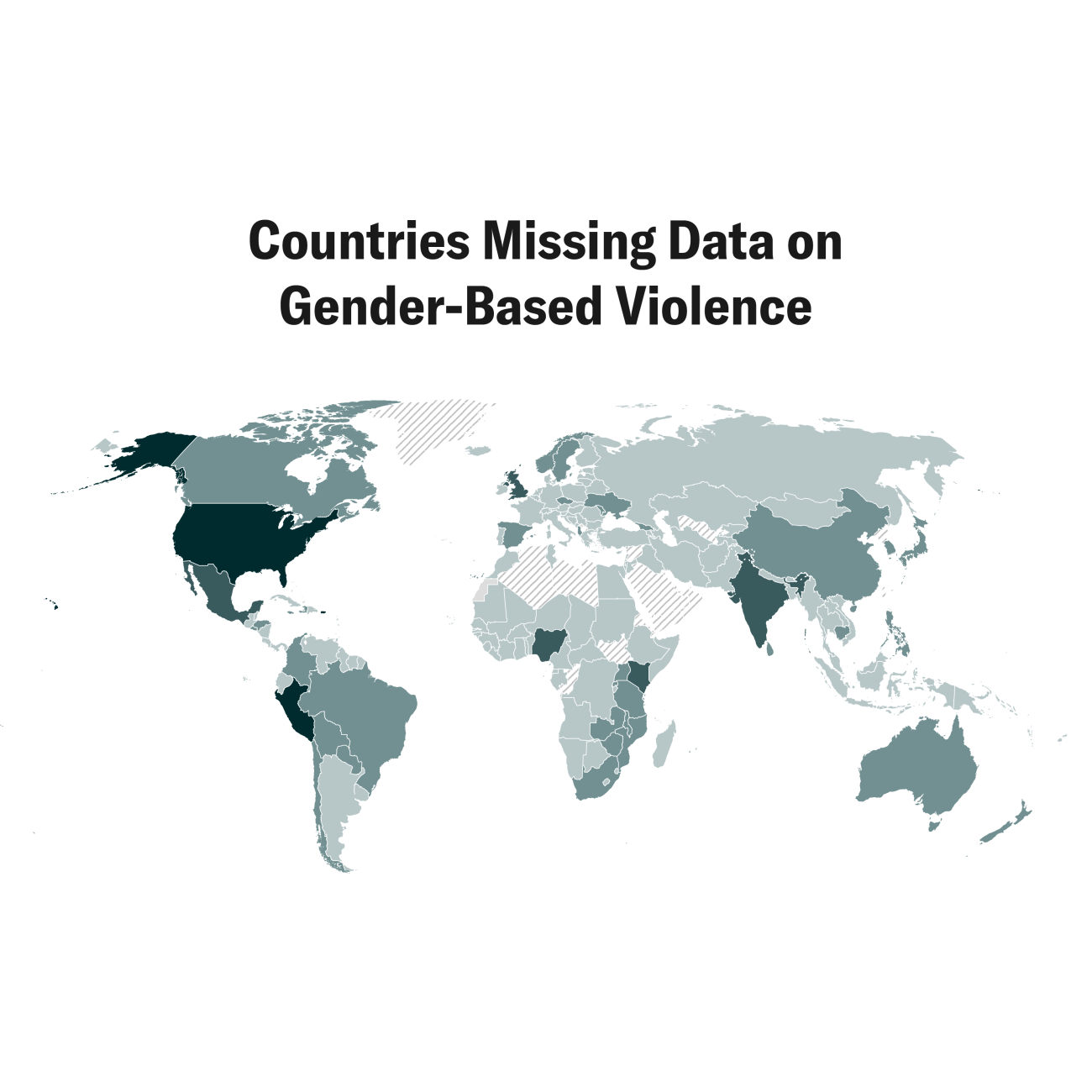

The first step toward improving transportation for women is to collect more gender-disaggregated data. Otherwise, women in a transport study can all report that they are unsafe, but the overall result could still seem like a low percentage if those women make up a small part of those surveyed. Safety may not be the top priority for everyone, but it’s a major issue for women, who make up half the actual population.

Moreover, crowdsourcing can help generate that gender-disaggregated data. A recent article from the Guardian describes some of these techniques, including having women map their perceptions of safety across a city. Women know where the problems are and what the problems are, and so they have the expertise to inform safety initiatives. Especially when women are not well represented in city planning decisions, their perspectives are critical to implementing solutions that work.

The second step is to garner political will, necessary to mobilize resources toward better infrastructure that promotes transport safety for women. This is where emphasizing the economic case for action may help.

A robust economy is a nearly universal goal, and like many other aspects of health, women’s safety is a part of achieving it.

Advocates can, and should, make the case that women can grow the economy when unnecessary barriers to employment, like harassment, are taken seriously and taken down. A robust economy is a nearly universal goal, and like many other aspects of health, women’s safety is a part of achieving it.

The final step is monitoring and enforcement. If police accept bribes from harassers, safety becomes a matter of personal resources, not of rights. If trans people are not able to access health services or participate in job initiatives because of their gender identity, then the solutions do not work for all women. If girls still must supplement safety solutions with their own types of protection, such as only traveling in groups, then the solutions have not solved enough.

Women’s health is not just maternal and reproductive health. After all, women are not just mothers and partners. When the most basic elements of daily life—like access to public transportation—regularly damage women’s safety, then it is a women’s health and global health issue and action is past due. The next time government officials want to increase their GDP, they should thank the women who courageously step on the bus each day, and then make it easier for others to join them.