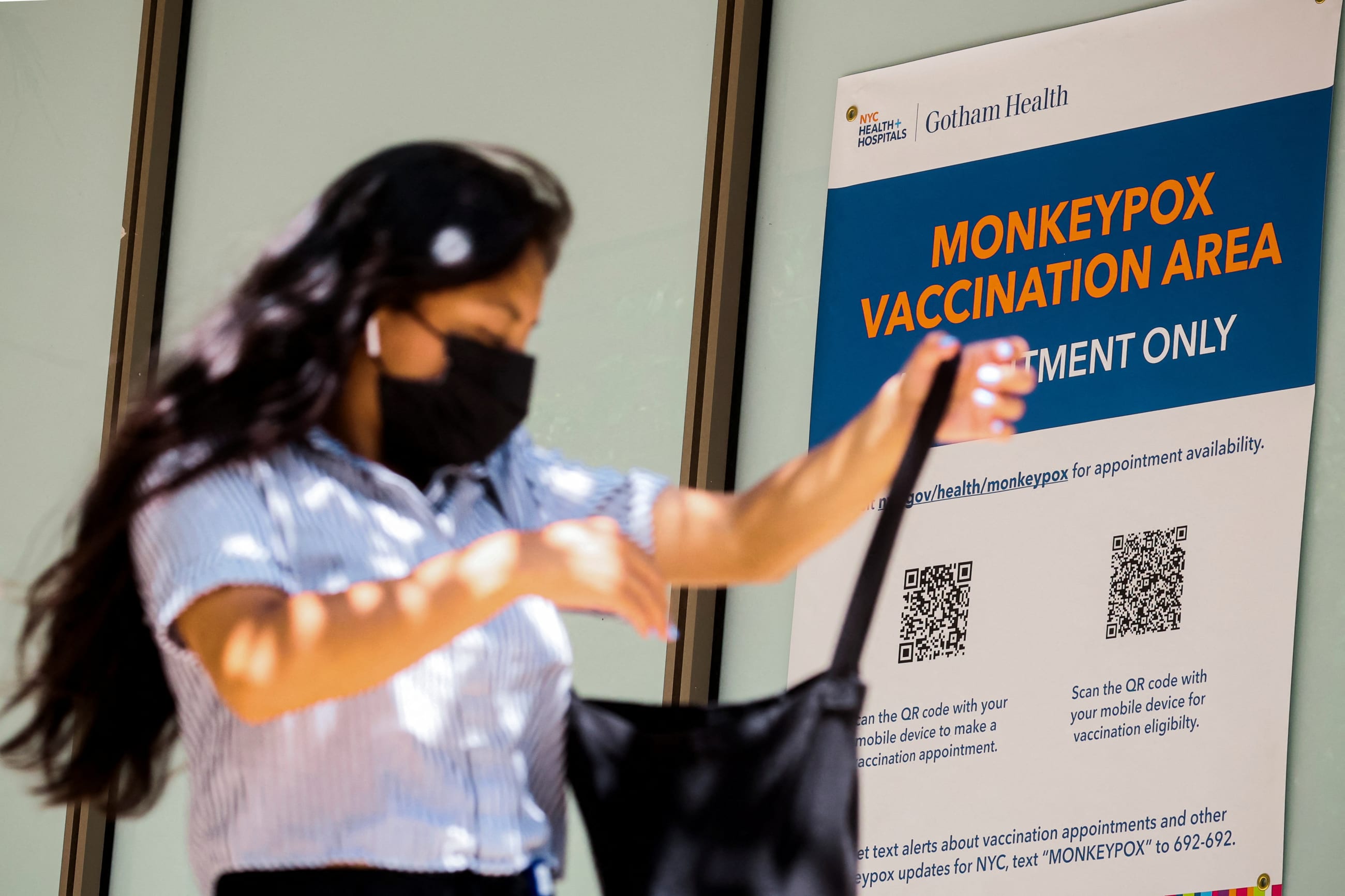

On July 23, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus declared monkeypox a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, against the advice of the WHO Emergency Committee. Over the next two weeks, similar public health emergency declarations were issued across the United States at the federal level, at the state level in California, New York, and Illinois, and even at the city level in San Francisco.

To better understand what these declarations mean for coordinating a health response to monkeypox in the United States, we spoke with Lindsay Wiley, a professor of law and faculty director of the Health Law and Policy Program at UCLA Law.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: What is a Public Health Emergency (PHE) declaration and what does it allow you to do that you couldn't do before?

Lindsay Wiley: The federal government has public health measures that it's allowed to use, generally at any time, but the administrative and legislative processes that are normally required can be time-consuming and tricky. Declaring an emergency just simplifies and expedites the processes required to invoke some of those already existing powers.

There are a lot of misconceptions about what a Public Health Emergency declaration at the federal level changes about the state of the law. There's a popular misconception that it means individual rights can be abrogated in different ways, sort of like declaring martial law. But that's not how public health emergency declarations work. The things that the Donald Trump and Joe Biden administrations did in response to COVID-19 that were most controversial weren't done in conjunction with a public health emergency declaration. The federal transit mask mandate or COVID-19 border restrictions were done using routine public health authorities. This declaration doesn't really change anything about that.

In the United States, what it primarily alters is the balance of authority between the administrative agencies at the federal level and Congress. Congress, under the Public Health Service Act, is essentially telling the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and its various sub-agencies, "here are some additional things that you can do without new congressional action." That mostly involves purchasing power and streamlined processes for government spending. It also allows the HHS and its various offices to suspend federal regulatory requirements if those regulations are barriers to the public health response. For example, it can allow the HHS to enhance reimbursement to clinicians or hospitals for treating monkeypox patients.

Confirmed Monkeypox Cases Since January 1, 2022

Think Global Health: What other tools does the U.S. government have to handle an outbreak like monkeypox and why did it choose this one over the other possibilities?

Lindsay Wiley: Declaring a PHE under the Public Health Service Act is generally the first step, although each public health emergency is different and presents different challenges. Monkeypox is a different virus than COVID-19, and [the U.S. government] already has some tools available for monkeypox because they were developed and approved in case of smallpox attacks. So that creates a different regulatory landscape. But it is common for a PHE to be the starting point in a scenario like this.

The second declaration the Biden administration made is an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) declaration for the JYNNEOS vaccine under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. EUAs are something everyone has become much more familiar with because of COVID-19. The considerations are a little different for monkeypox, because with COVID, there weren't really any available tests, vaccines, or treatments at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, so it really was about incentivizing, developing, and being able to purchase and approve new countermeasures. With monkeypox, the United States is dealing with vaccines, treatments, and tests that already exist, but they are being used off-label in some cases because they were approved for smallpox, not monkeypox. The other quirk is that they're being held in the Strategic National Stockpile, which is a repository of potential countermeasures that could be used in the event of a bioterrorism attack or other emergency

For a while, the government held off on using the emergency use authorization mechanism (EUA) for monkeypox. Instead, it used a research mechanism. Before the EUA was issued in relation to monkeypox, each time a clinician wanted to prescribe Tpoxx, a treatment that's available for monkeypox, they had to submit paperwork under an expanded access protocol for an investigational new drug—what's colloquially called "compassionate use"—when clinicians prescribe an investigational drug that's being studied but for a patient who isn't enrolled in the study.

The third potential federal declaration is a PREP Act Declaration, which can be used to shield manufacturers, distributors, clinicians, pharmacists, and health care institutions like hospitals from liability for covered countermeasures. For example, if the United States ultimately decided that it wanted to use the more controversial smallpox vaccine with a higher risk profile, the ACAM2000 vaccine, it could shield clinicians from liability for complications that could arise from that vaccine. The second thing that a PREP Act declaration can do is give federal agencies more authority to expand the scope of practice for professionals, like pharmacists, to administer vaccines. However, there has not been any reporting that the administration is planning to issue that yet.

Think Global Health: When it came to issuing a federal PHE declaration, there were reports that there was real division within the administration about whether to issue a PHE at this time. What kind of reservations did experts have about issuing a PHE declaration for monkeypox?

Lindsay Wiley: Some of the concerns that have reportedly been raised within the administration include concern about increasing stigma for the population that's primarily affected to date—men who have sex with men and their sexual networks—that issuing the emergency declaration could exacerbate that stigma by setting off undue panic among the broader population.

Another concern is whether this is really the right mechanism. For example, Tpoxx, the treatment that's available for monkeypox, is difficult to access. So far, the EUA Declaration for monkeypox only covers vaccines. Antivirals like Tpoxx aren't covered yet. Some experts are concerned that if the administration were to issue an EUA covering Tpoxx, researchers might not learn as much about whether Tpoxx is actually effective in monkeypox patients. It was approved for smallpox based on animal studies, and for now, can only be used only under the compassionate use mechanism, which restricts access and imposes a significant administrative burden of paperwork on clinicians who want to treat monkeypox patients using Tpoxx. EUAs could make such treatments more readily available, but they can also make it harder to track how effective they are.

Think Global Health: How often are PHE declarations issued and under what circumstances? Are they used more frequently now than in the past?

Lindsay Wiley: They're issued quite commonly for things that don't necessarily make the national news, for example lots of natural and weather-related disasters. Tornadoes, mudslides, and even severe thunderstorms have triggered PHE declarations in a specific state. As recently as August 2, two days before the monkeypox declaration, there was a PHE declaration in the state of Kentucky as a result of the severe storms and flooding there.

Maybe they are used more frequently now than in the past, but if so, it could be because of changing conditions. The United States has developed better tools for responding to severe weather events and disease outbreaks, but those tools are often expensive and state and local governments often don't have sufficient resources to deploy a full response. So, bringing federal funding into play is something that's needed more frequently than it was 20-30 years ago.

On the other side of things, health-care regulations from the federal government have become more extensive over the last few decades. The other big thing a PHE declaration does is allow the administration to temporarily suspend or alter those health-care regulations, to make sure they're not standing in the way of the public health response.

Think Global Health: Are there any downsides to issuing a declaration?

Lindsay Wiley: There's lots of discussion about that, especially for declarations that have pushed the envelope. Pre-2020, the most controversial use of declarations was for the opioid overdose crisis by state and local governments. There's been recent controversy over calls for the Biden administration to use the public health emergency declaration mechanisms in response to the Dobbs decision overturning Roe vs. Wade, to increase access to medication abortion. Then there was controversy over the timing of issuing an emergency declaration for monkeypox.

There's emergency fatigue, the idea that the more frequently these mechanisms are used, the weaker their signaling effect is. There's also concern about prompting public panic or over-estimation of the risk to the general public. Then there's a separate question about whether these authorities are needed. And is enhanced funding needed to prevent more widespread transmission from occurring? But that can also prompt an overreaction, which can trigger stigma, discrimination, or even violence against the population that's perceived as the source of the threat. So, those are some of the considerations that come into play.

The final worry that was triggered by the opioid declarations and by the proposal to declare lack of access to abortion a public health emergency is that they can be challenged in court. Those challenges could ultimately result in precedents that limit authority for public health emergency response going forward.

There's emergency fatigue, the idea that the more frequently these mechanisms are used, the weaker their signaling effect is

Think Global Health: Are there lessons that can be taken from COVID-19, or previous public health emergencies that are useful in that have taught us things about how to handle a monkeypox outbreak?

Lindsay Wiley: I think the COVID experience and what it teaches various audiences is complicated. One concern is that the backlash against COVID emergency response measures could slow the response to monkeypox. For example, I wouldn't be surprised if the delay in declaring monkeypox a public health emergency at the federal level, and at the state and local level, was caused in part because of the misperception that this was going to mean another round of intrusive public health measures and fear of backlash against the declaration as a result of that misperception. There has been some rhetoric and commentary indicating fears that the government would impose mask mandates or close schools over monkeypox, even though there are no indications that that's being seriously considered.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are those who feel strongly that the government didn't take COVID-19 as seriously as it should have, and that it's happening again with monkeypox. So, when CDC and other public health experts try to reassure the general public that monkeypox doesn't linger in the air and isn't spread through short periods of casual contact, some people are very distrustful of that advice. There's a public-health backlash because of the COVID experience and it's coming from multiple directions.