More than 1.5 billion people experience some form of hearing loss. However, relatively few organizations conduct research on Deaf people or the challenges that they face.

Global Deaf Research Institute (GDRI), alongside other deaf advocacy organizations, is now working to ensure quality data collection that captures the widespread diversity within Deaf communities, including those who identify as culturally Deaf—spelled with an uppercase D—and those who do not. Even though hearing loss is the fourth most common type of disability as of 2018, negative health outcomes, including higher chances of mental health issues such as depression and anxiety and higher likelihoods of traumatic childhood events relative to hearing people, are often underreported in mainstream research, according to GDRI, established in May 2023 by and for Deaf people.

Lorne Farovitch, founder of GDRI and a Deaf bioscientist and advocate with an extensive research career, was frustrated at the negligence of Deaf people in mainstream research. This became the driving factor behind GDRI. As a researcher, Farovitch recognized the need for better data on Deaf people so that organizations across the world would have stronger backing for their advocacy of accessibility policies.

Today, not enough establishments understand the wide variety in levels of deafness and only attempt to find solutions for one subgroup and believing them to be applicable to all Deaf people.

Today, not enough establishments understand the wide variety in levels of deafness

"Deaf people have so many subgroups, each of them with different communication needs. There's no one-size-fits-all," said Farovitch. Although every single person with hearing loss is deaf, how they define their deafness varies widely.

The term deaf has been used to encompass all types of deafness, from hard-of-hearing people to Deaf people who are born and raised in Deaf cultures and communities, to people who have lost their hearing due to accidents or illnesses, and everyone in between. Deafness has become a unique part of many Deaf people's identities rather than a disability.

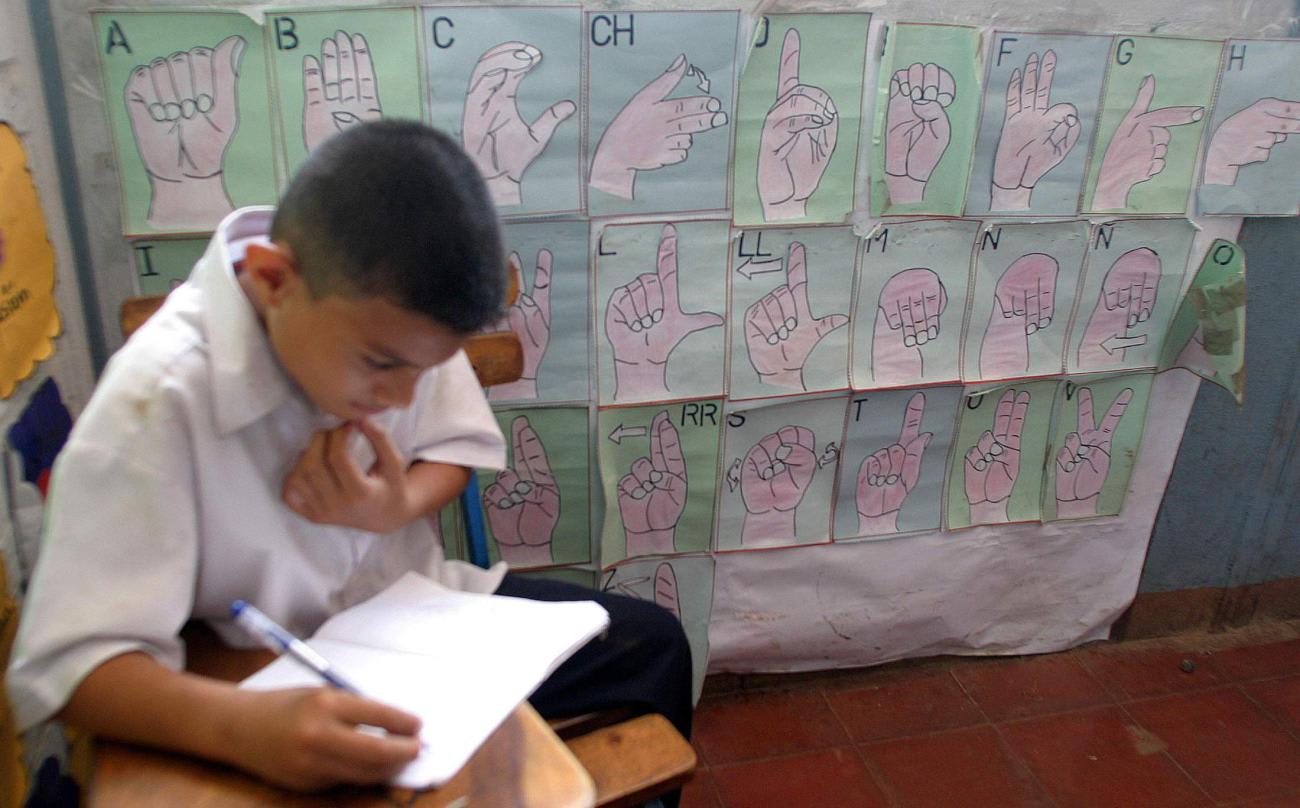

But regardless of how big or small a role deafness plays in people's identities, "Deaf people have universal experiences," Farovitch believes. These shared experiences have motivated GDRI to not focus on any subgroup of Deaf people. GDRI hopes to help all Deaf people by collecting qualitative data in countries that lack support or accessibility efforts. GDRI is starting its mission in Ecuador, where Farovitch and other scientists are surveying Deaf people to help the National Federation of Deaf People of Ecuador build proof and arguments to present to policymakers to effect change that allows better accessibility.

GDRI isn't the only organization fighting to improve the quality of life of Deaf people. As it works to collect data to help organizations push for policy changes in their respective countries, Deaf Worlds (DDW) is helping local Deaf communities preserve their languages and cultures.

DDW provides resources and customized aid to Deaf people, focusing primarily on signing Deaf communities rather than all Deaf people. It does so because many small Deaf communities use local sign languages as opposed to widespread sign languages, such as American Sign Language (ASL).

"We collaborated with Deaf leaders to protect and revitalize these languages, recognizing their cultural and linguistic value," Sachiko Flores, the executive director of Deaf Worlds, explained in an email. For example, DDW has undertaken initiatives to work with Filipino and Nigerian leaders in their respective communities and is working to "document and promote Filipino Sign Language . . . as a primary language for Deaf education" for the Filipino community, affirming their linguistic identity, according to Flores.

DDW is doing similar work with the Hausa Sign Language for a Nigerian Deaf community, among others around the world and their respective languages. By supporting communities' unique languages, DDW can help communities enact solutions that are culturally and contextually appropriate. "Our partnerships are rooted in mutual respect and a shared commitment to empowering Deaf individuals," Flores wrote.

Another organization aiming to empower Deaf individuals is Atomic Hands, a Deaf-led nonprofit organization that focuses on expanding ASL for Deaf people who specialize in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields (STEM).

Whereas GDRI and DDW work on breaking down barriers with data and support of local communities, Atomic Hands focuses on progress by developing signs for STEM terms without universal signs. Currently Atomic Hands creates signs for ASL, but cofounders Barbara Spiecker and Alicia Wooten explain that they have "honed a framework that [they] hope to share with organizations worldwide, enabling them to adapt it to their unique communities."

Atomic Hands began when Spiecker and Wooten shared their struggle with the lack of signs in STEM fields. "Historically, communicating technical ideas in ASL relied on initialized signs, fingerspelling, or borrowing terms from English, which often led to inefficiencies and confusion. The lack of conceptually accurate signs made it challenging to fully articulate and connect with scientific content," they explained in an email.

Frustrated by this gap—like Farovitch—they pondered how to break down this barrier as they attended a 2017 Deaf Academics Conference in Copenhagen, Denmark. There they met hundreds of other deaf scientists who also faced challenges with the lack of signs for STEM terms. Inspired by the conference, Spiecker and Wooten decided to found Atomic Hands the same year.

The cofounders worked to develop signs for STEM concepts so that future aspiring Deaf people could avoid experiencing the same difficulty they had. By developing signs for STEM terms, Atomic Hands is helping Deaf people learn and understand these concepts better, bridging a gap in language that will allow Deaf people specializing in STEM to learn better.

Atomic Hands also promotes collaboration and unity among Deaf people specializing in STEM. The organization builds networks for Deaf scientists, encouraging teamwork and community among those who rely on interpreters. With these networks, Deaf STEM students and experts can find a sense of community even within their own complex field.

Together, these companies along with others are making progress toward breaking down barriers for those in the deaf communities

"Through efforts like those at Atomic Hands and collaborations within the broader Deaf STEM community, we now have more intuitive and linguistically accurate signs," the cofounders wrote in an email. These developed signs help Deaf people in STEM convey scientific ideas in a direct way with signs than continue to rely on fingerspelling—spelling out a word letter by letter rather than saying the entire word—and flimsy English translations.

"These developments enable clearer communication, faster comprehension of complex topics, and a deeper engagement with our fields of study," Spiecker and Wooten explained.

Together, these companies, along with others, are making progress toward breaking down barriers for those in deaf communities. However, much work remains. More than 90% of Deaf people are born to hearing parents worldwide, but not all of them have the same opportunities to access Deaf education or signed languages. Because of this lack of accessibility, as of 2019, fewer Deaf people than hearing people have completed high school or college.

GDRI's spotlight on research and qualitative data, DDW's collaboration with various Deaf communities, and Atomic Hands' efforts to expand ASL vocabulary, along with other organizations dedicated to helping Deaf people, are finding more tools and services to overcome these challenges one by one.