As 2021 ends, COVID-19 remains a dangerous pandemic. In 2022, the battle continues but will fail unless the United States and other countries deliver the billions of promised vaccine doses. The new year will also require states to make decisions about handling future pandemics. Over the past twelve months, governments, the World Health Organization (WHO), and other international bodies have explored how to better prepare for pandemics. Despite this diplomacy, what pandemic governance will look like beyond COVID-19 remains inchoate. The outcome of the recent special session of the World Health Assembly (WHA) captures the indecision and uncertainty hanging over pandemic governance reform.

The recent special session of the World Health Assembly captured the indecision and uncertainty hanging over pandemic governance reform

At the session, the WHA established an intergovernmental negotiating body (INB) to "negotiate a WHO convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response." This decision left unanswered two questions debated throughout 2021—what form a pandemic accord should take and what issues it should address. In the INB, WHO members will need to answer these questions—and how the United States responds will strongly influence the INB's impact on pandemic governance.

To Treaty, or Not to Treaty, That Might No Longer Be the Question

The INB's establishment originates from a campaign that began last year and accelerated during 2021 for WHO members to adopt a treaty to strengthen pandemic governance. Under the INB's mandate, a treaty remains a possibility. But the WHA special session marked the second time that countries did not support the treaty strategy over other options.

In May, the WHA did not embrace calls from government leaders, the WHO Director-General, and the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response for negotiating a treaty. Instead, it decided that a special session of the assembly should consider a treaty and other possible instruments. In the run-up to the session, the effort to advance a pandemic treaty intensified. However, WHO members did not favor the treaty approach at the session and mandated that the INB consider all possible instruments.

The repeated refusal of WHO members to privilege a treaty reflects sustained opposition, ambivalence, and indecision among WHO members about this strategy. The broad scope for negotiations looks like a "lowest common denominator" outcome on an issue where governments cannot agree. It is not clear if the treaty approach will fare any better in the INB, especially after months of advocacy for a treaty twice failed to produce the desired result.

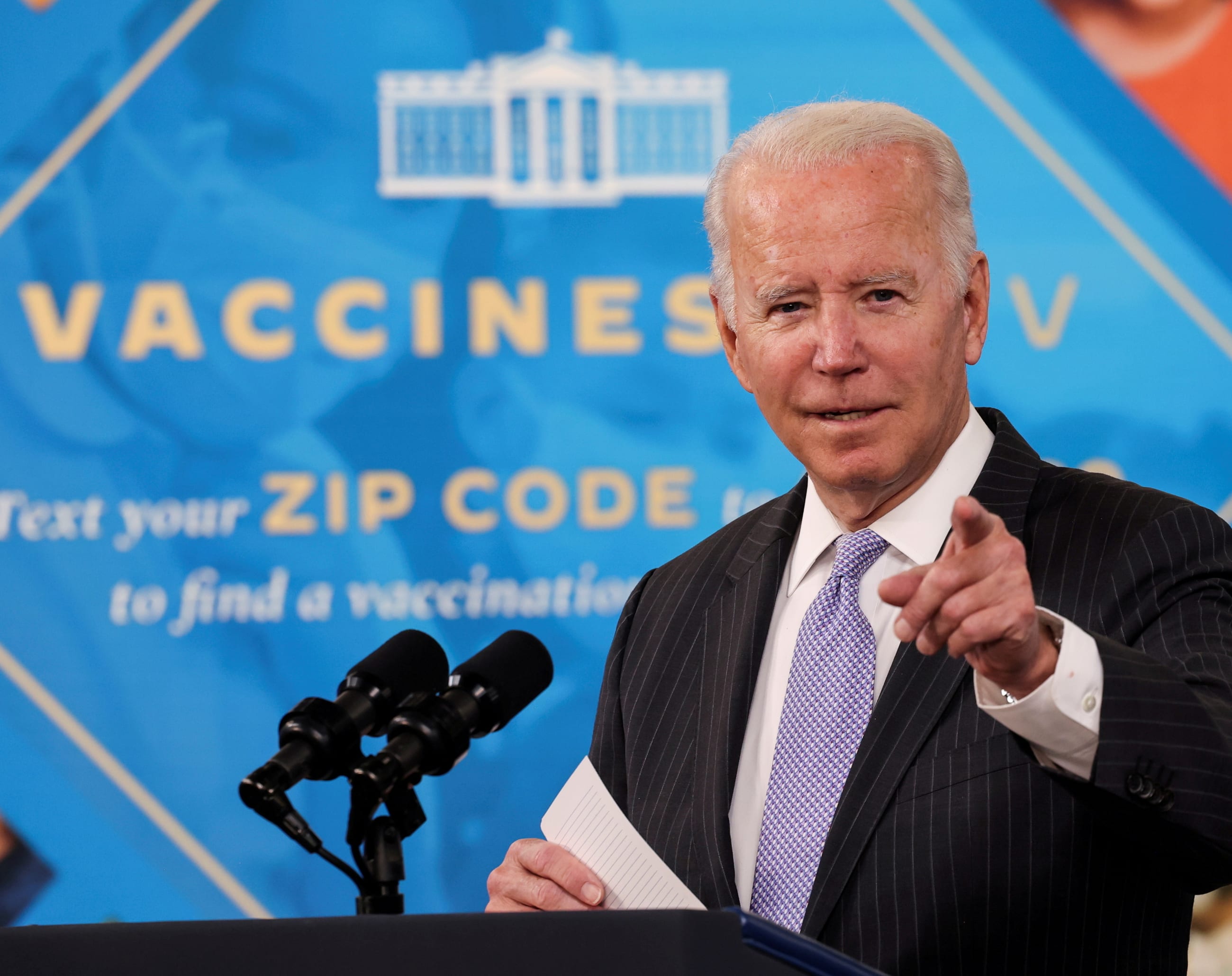

In the INB, the lowest-common-denominator agreement will be a non-binding instrument. This outcome appears to be what the United States wants. The U.S. government has agreed to include the treaty option in the WHA's decisions, and U.S. officials have used careful language in discussing it. But the United States has not supported the treaty idea. Instead, U.S. officials have embraced revising the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR). Nothing on the horizon suggests that the INB's negotiations will make the United States prefer a treaty. The pandemic governance reforms that President Joe Biden is pursuing do not require a treaty. Supporting a treaty would bring President Biden and the Democratic Party no political benefits in the mid-term U.S. elections in 2022.

When the INB convenes, WHO members interested in a treaty must assess whether it could function without U.S. participation. Many countries will conclude—if they have not already—that a treaty will not work without the United States, increasing incentives to support a non-binding agreement. Treaties can succeed without U.S. involvement, as the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control demonstrates. However, pandemic governance is a challenge for which U.S. power and influence matters. Without U.S. support, the remaining high-income governments supportive of a treaty would have to bear more of the treaty's diplomatic and financial burdens. These increased, long-term burdens might change political calculations to favor a non-binding agreement.

Months of advocacy for a treaty twice failed to produce the desired result

Fewer Things for Pandemic Governance than are Dreamt of in Global Health

The INB will also force countries to decide what they want in a pandemic accord. The WHA decisions contained no guidance on the content of a pandemic agreement. The INB must consider the report from the Working Group on Strengthening WHO Preparedness and Response to Health Emergencies, which describes many topics that the group discussed. But the report does not illuminate how countries might prioritize issues in reforming pandemic governance.

Several topics in the report create incentives for adopting a non-binding instrument. For example, the report identified equity, universal health coverage, and financing as important. Historically, high-income states have rarely, if ever, accepted binding legal obligations to transfer financial or technological resources to achieve equity or build health systems in other countries. Other topics—such as outbreak detection and pathogen sample sharing—are covered under different treaties, which constrains how a pandemic treaty could handle such issues. In both cases, a non-binding approach might be more attractive to states.

In addition, the absence of guidance in the WHA decisions and the many topics in the working group's report signal that countries do not agree on what a pandemic instrument should do. The INB is open to all WHO members, so it must consider what each one wants. As happens in all multilateral negotiations, the INB will have to cull the "wish list" and identify where agreement is possible. Such triage usually bears the imprint of the most powerful states, including the United States.

What the United States seeks from a WHO pandemic instrument is not clear. The U.S. government is already pushing for governance reforms, such as a pandemic financing facility, that will not wait for INB negotiations to conclude. New, transformative moves, such as direct cooperation with China on health security, do not need INB deliberations.The United States is harnessing many diplomatic mechanisms, including the Group of Seven and the Group of Twenty, to strengthen pandemic governance—an approach that INB talks will not change. The United States will press ahead with its reform agenda and, in the process, do more to shape the INB negotiations than vice versa over the remainder of President Biden's time in office.

For the United States, the content of an INB-negotiated instrument is of tactical interest rather than strategic importance. In foreign policy terms, the instrument should facilitate ongoing U.S. pandemic governance reform efforts, open new opportunities for these activities, preserve policy flexibility and autonomy, and avoid exacerbating friction on issues that the United States confronts in global health, such as intellectual property rights.

If It Be Not Now, Yet Will It Come?

Determining how to avoid another catastrophic pandemic during an ongoing pandemic was never going to be easy, so the indecision reflected in the INB's mandate is not shocking. Accusations of "travel apartheid" and booster-exacerbated "vaccine apartheid" triggered by national responses to the omicron variant underscore how difficult transforming pandemic governance will be. Indeed, the omicron episode potentially reveals that the fault line in global health between national sovereignty and security, on the one hand, and global solidarity and equity, on the other, has become more entrenched, unstable, and dangerous during COVID-19. If so, neither U.S. power nor the INB will produce the sea change so many hoped this epic plague would bring.