Global health has a money problem that is about to get much worse with the Donald Trump administration's wholesale reduction of funding in global health. Program funding is in short supply, budgets have been cut, institutions can't adequately fundraise, and donors are looking to new priorities, such as climate change.

Given those constraints and the difficulty of negotiating a pandemic treaty in the current geopolitical climate characterized by a lack of international cooperation, Akhila Potluru and I decided to uncover how much the international community is spending on the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB)—which was established to develop the Pandemic Treaty—and if the money could have been spent differently for enhanced pandemic preparedness.

The research found that the INB cost $201 million, at a conservative estimate. Thus we underscore the high financial and opportunity costs of the INB, questioning its efficiency in achieving global health security goals equitably. Although negotiations are essential for setting international norms, their limited tangible outcomes and inequitable distribution of costs call for a more strategic approach to pandemic preparedness financing. This should include a commitment to detailed cost estimates transparently published, as well as attempts to reduce costs, or distribute them more equally before initiating negotiations.

The INB's Origins

The INB was established in 2021 to draft and negotiate an international instrument to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response. The initial process was to yield a resolution by May 2024, but given an overly ambitious agenda—and a fundamental lack of consensus on key issues including One Health, financing, and pathogen access and benefit sharing—the deadline was extended to May 2025.

The Intergovernmental Negotiating Body cost $201 million, conservatively

To estimate the total cost, the study analyzed three categories of expenses: human (the people negotiating the treaty and their teams back in capital cities directing policy priorities) totaling $163.8 million; travel (for negotiators to travel to Geneva for each round of the INB negotiations) totaling $32.2 million; and organizational (the cost of hosting the INB, including paying staff and translators) totaling $5.3 million. This equals approximately $201 million for the INB process, at a conservative estimate.

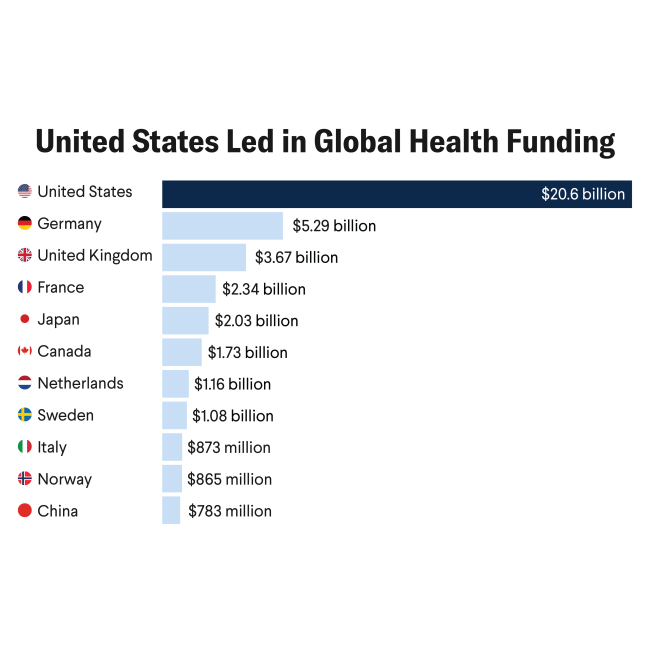

To help contextualize those figures, the study estimated that achieving pandemic preparedness—unlikely in the immediate future—would cost $31.8 billion. The INB's estimated cost is 0.63% of that amount. That cost also equates to approximately 3% of the World Health Organization's (WHO's) Biennium Program Budget (total budget for 2025–27) that covers all WHO activities. More broadly, the INB cost is 20% of the $1.28 billion that the U.S. government, the largest contributor to the WHO, committed to the organization from 2022 to 2023.

The U.S. withdrawal from the WHO has prompted additional concerns about financing gaps. The WHO has noted that it has not yet raised the money to cover the cost of the INB process internally. The $201 million cost thus raises four points of consideration:

- The money could have been spent in other ways for enhancing pandemic preparedness and response. Some uses include purchasing either 120 million COVID-19 vaccines, 17,586 doctors or 56,229 nurses in India, or 3,801 doctors or 12,229 nurses in Brazil. Investing in preventative efforts or workforce strengthening for enhanced preparedness could have saved lives and slowed the momentum of the pandemic. Such opportunity costs need to be given more consideration by the WHO, given that whatever agreement emerges from the INB process will likely be superficial and not inspire meaningful change.

- Although all WHO member states contributed to the cost of the INB, participation was not equitable. Discrepancies are vast between the size of teams participating and how many can afford travel to Geneva for the negotiations. This has meant unequal participation, leaving the larger delegations with stronger negotiating power. Member states without permanent representation in Geneva or that are unable to staff negotiators have been severely disadvantaged. This also does not account for the distances some participants need to travel to join the negotiations or the personal strain of spending away from home.

- Costs should be considered in the context of the effectiveness of multilateral negotiations. The WHO has only used its treaty-making powers twice before, for the negotiation of the International Health Regulations in 2005 and for the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control in 2003. Those treaties have been mixed successes and have resulted in both tensions surrounding implementation and an unequal balance of power in international cooperation agreements. This raises doubts about whether the INB process will yield meaningful outcomes, especially given ongoing political and financial constraints.

It is difficult to compare the cost of the INB with those of other multilateral processes because cost estimates are not available for other multilateral treaty-making processes. The study provides the first detailed financial assessment of multilateral treaty-making and could provide food for thought for other sectors of multilateralism. Moreover, its calculations are almost certainly an underestimate, and the true cost of the INB is likely much higher. After publishing the paper, several delegations informed us that the volume of staff time we accounted for is a vast underestimate; the analysis also excludes informal meetings and indirect costs, such as teams working on specific overlapping issue areas in capitals related to treaty negotiations.

Given those considerations, governments should undertake a cost benefit analysis before launching into new negotiation processes, such as those touted for a Conference of the Parties or development of future protocols associated with the INB, which will have similar costs.