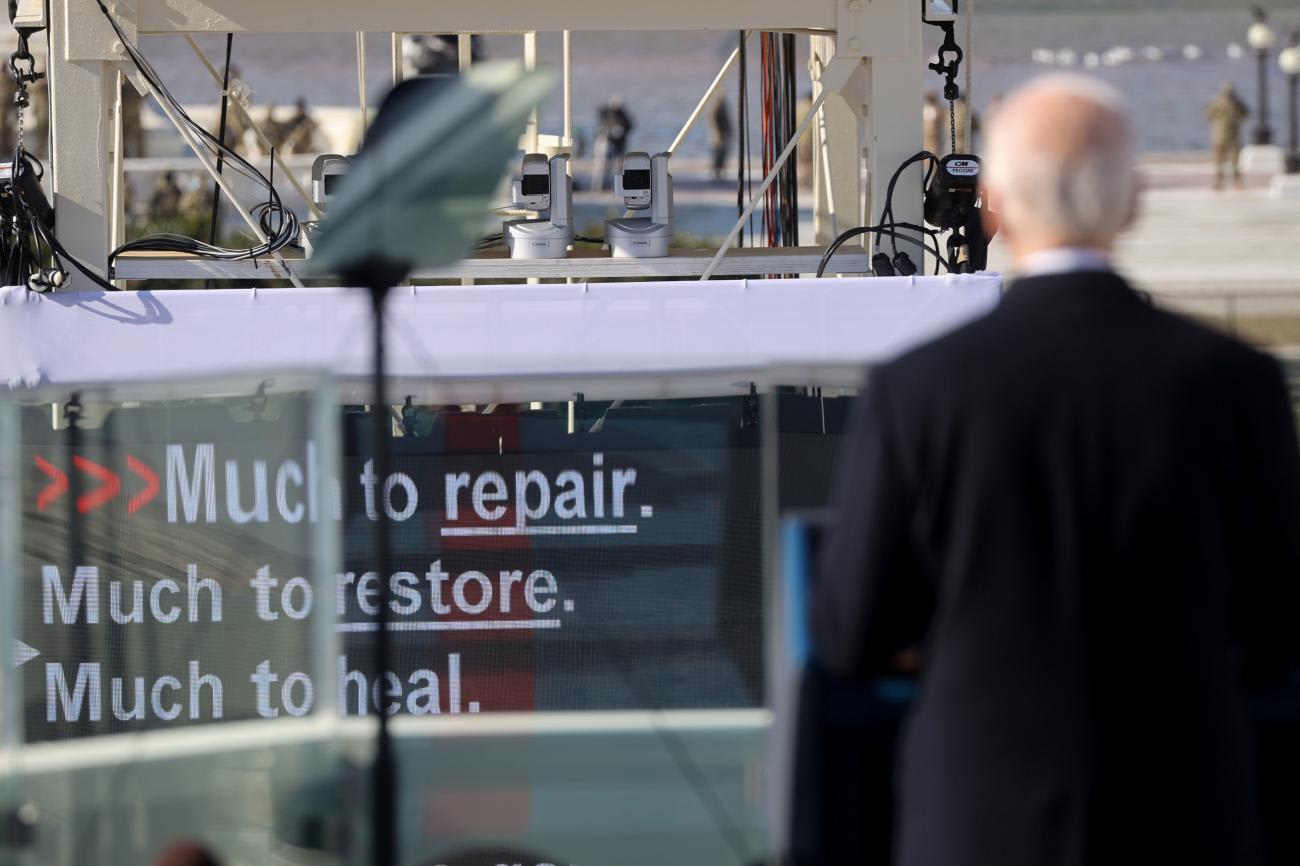

Four years from now, the United States could establish itself as a global leader promoting strong democratic institutions, social and economic justice, and collective action to fight climate change. But getting there will require earning back the trust of potential allies near and far and fulfilling obligations beyond our borders. The first steps the Biden-Harris administration and the 117th Congress can take on that path to good global citizenship will be their contribution to worldwide pandemic response and recovery, in the first six months of 2021.

Step 1. Support COVID-19 Immunization Through COVAX

In September, with a speed and determination rarely seen on the global stage, the global vaccine alliance, Gavi, established the COVAX Advance Market Commitment to guarantee low-income countries would have access to safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines. The facility secured $360 million in donations from the European Commission, France, Spain, South Korea, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, but the U.S. government has been conspicuously absent from this effort.

COVAX has agreements in place to procure about two billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines

Now that COVID-19 vaccines that can be used in resource-poor settings are on the horizon, COVAX has agreements in place to procure about two billion doses. These could be made available to 92 eligible countries and protect up to 20 percent of the population. But making this promise real will require an additional $5 billion in 2021.

This gives the incoming Biden-Harris administration a huge opportunity: on day one, the United States should join COVAX. Helpfully, Congress has set the stage by including $4 billion for Gavi in the coronavirus relief bill, which can be used for vaccine purchase. In a single move, funding COVAX would signal an urgently needed pivot away from vaccine nationalism and toward global solidarity.

Step 2. Rebuild the Relationship With the World Health Organization

If the World Health Organization (WHO) didn't exist before, we would create it now. All nations benefit from an international body that can establish standards for infectious disease reporting, marshal resources for rapid responses to emerging health threats, synthesize global biomedical and public health knowledge for national application, and convene technical experts around shared challenges in public health.

In the future, as has been true at some times in the past, the United States should be among the leading voices within the WHO, bringing deep pockets and deeper scientific expertise. Beyond merely reversing President Trump's April 2020 decision to halt funding to the WHO, the Biden-Harris administration could make additional funding available to the WHO on a matching basis, contingent on core voluntary contributions from other donors. This would provide the organization with a much-needed boost in flexible and diversified resources.

In addition to providing one of the world's vital institutions with resources necessary to do its work, greater contributions from the United States could help address longstanding concerns about WHO governance and transparency around data. In the spirit of multilateralism, the U.S. government could also be clear about the quality of leadership it expects and offer the support of American technical experts.

Step 3. Unify Global Health Assistance Around an Evidence-Based, Justice-Informed Framework Jointly Developed with National Governments

About one-third of all U.S. development assistance is dedicated to global health, the largest share of which is allocated through the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Many countries receiving that assistance do so in fragmented fashion across multiple disconnected programs. For example, the USAID Mission in Kenya cites 23 distinct projects and funding streams, from pharmaceutical supply chain management to child welfare services for orphans, from health informatics to HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment among people addicted to drugs.

The United States could and should take a more coordinated, holistic approach to global health assistance for low-income countries – and that approach can be informed by what we have learned so painfully during the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As we've seen, proven technologies and enormous financial resources can only solve major public health problems when leadership elevates evidence, when roles and responsibilities are clear, and when governments prioritize the most vulnerable people, within and beyond the health system. In other words, global health funding does the most good when the underlying, in-country conditions are right.

About one-third of all U.S. development assistance is dedicated to global health

To develop an updated, COVID-19-and-beyond framework for global health assistance, the U.S. government could draw inspiration from its own Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). The MCC is based on the notion that development assistance yields the greatest returns when recipient countries have strong governance. It uses established criteria to determine which countries are eligible, and then makes large investments towards their nationally determined priorities; countries that don't meet the criteria are offered targeted assistance to redress shortcomings. Research has found that transparent application of the criteria, combined with assistance that responds to country-owned priorities, creates an incentive for the adoption of governance reforms.

The majority of global health assistance could be distributed in a similar fashion, and countries could earn eligibility by showing that public health investments will bear fruit. Choosing optimal criteria for eligibility would require deep study of the existing evidence along with robust debate, particularly with experts from relevant countries and regions, but here's a starting point: governments should demonstrate they are committed to mitigating geographic disparities, adopt and enforce occupational safety regulations, adopt and enforce core human rights protections, provide schooling equitably, and select gender-balanced leadership for national health institutions. Global health assistance for eligible countries could be jointly designed with government counterparts so the agreed programs would fit into national plans rather than reflecting priorities of outside advocates.

These three steps represent both a response to the current health emergency and the foundation of strong public health systems around the world. While they cannot be fully implemented without agreement by the U.S. Congress, they are not a hard sell politically: global health has traditionally benefited from broad, bipartisan support. Moreover, the coronavirus pandemic has made it impossible to deny that weaknesses in public health systems – whether in the United States or abroad – create profound social, economic, and security risks for us all. Taken together, these steps would show the world that the United States is returning with good will to the community of nations, and ready to do the work.