I think often about Dr. Paul Farmer—the world-famous global health pioneer and founder of Partners In Health—and even more so today, the anniversary of his passing in 2022. Over the past few years, core ideas that Farmer cared deeply about have come into vogue. National Public Radio covers the "structural violence" of social and health inequality. The Atlantic publishes features on social medicine. The Economist reported recently that "trust-based giving" is now in. Fox News uses the word "equity."

Farmer began corresponding with me in the early 1980s while he was a sophomore at Duke University. He wanted to be a medical anthropologist like me and came to Harvard to do his MD-PhD under my supervision. So I started as his mentor and over four decades we became close friends. Eventually he became a mentor for me as well. What drew us together was a commitment to using anthropology to improve clinical care by making it more human.

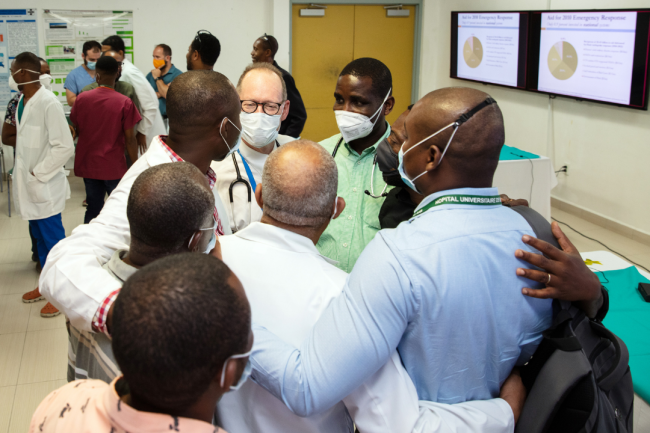

Farmer developed the idea of accompaniment. He borrowed it initially from liberation theology and turned it into the guiding practice for clinical work among desperate and poor HIV/AIDS patients in Haiti, those suffering from multidrug resistant TB in Peru, and terrified Ebola patients in West Africa. He theorized a form of care centered on caregivers' responsibility to their patients that emphasized their ongoing practical and moral presence and commitment to keep treating patients over the course of an illness. That concept, however, is still little discussed and understood. This is only one example of the need to put social theories to work in the practical service of improving lives and repairing societies.

For Farmer, like other medical anthropologists, in treating disease pathology (such as bacteria causing inflammation in the lungs), health-care workers all too frequently overlook the patient's and family's illness experience: their struggles with the coughing, chest pain, shortness of breath, and fear of serious suffering and real-life disability. As Farmer so powerfully demonstrated over the decades, especially in the most urgent circumstances and often clinical deserts, the moral responsibility of the healer is to step inside patients' experiences and accompany them through the worst moments with empathy and expertise, compassion and care, for as long as it takes.

Farmer could be found walking distances, crossing streams, and climbing hills in his everyday care for his patients. He also followed up with them, even if that meant going with little sleep so that he could stay in better contact with patients and friends who were ill in different villages, neighborhoods, and even continents. He modeled accompaniment for many others as a way of living that is more foundational to medicine and health-care systems than the dominant emphasis on organizational norms and economic efficiency. He would not accept scarcity of resources as a reason that the poorest could not receive technologically adequate care, and he showed repeatedly that the necessary resources could almost always be found and mobilized. In so doing, he rejected the socialization for scarcity, which is ordinarily built into public health training and work. To do so, he drew on social theory for both critique and social action.

The passion behind that wisdom came out of Farmer's first experience in rural Haiti. The desperate poverty shocked him to the core. He once confided in me that he realized then in his innermost being that this was his call to act and to persuade others to act with him, as he put it, to "repair the world." He said it with dead seriousness before offering his winning smile and a self-depreciating joke. Accompaniment was his method, but also his life.

The moral responsibility of the healer is to step inside patients' experiences and accompany them through the worst moments with empathy and expertise

Farmer transferred what Aristotle called phronesis—practical wisdom and action for the art of living—to Partners In Health, the NGO he co-created to translate social ideas about equity and justice into social care for those with the greatest need and the least resources. Partners In Health has institutionalized Farmer's charismatic model of accompanying those whom the world treats as lesser into its on-the-ground programs, hospitals, and the work of its practitioners. It is the breathtaking audacity of that idea and practice of accompaniment that continues to animate staff, supporters, and funders—of whom are enthralled by his model of love and care and what it accomplishes in this broken world to keep bending the arc of social justice. The ways in which Farmer lived his mission, animates us and touches our souls.

I have spoken with several of Paul's former students and coworkers who were drawn by his example into global health work in some of the same desperate settings. They all said that his perseverance motivated them to do the same, but inevitably realized that the scope and scale of his work could not be replicated. Nonetheless, because of his example, they kept trying. The point is not to become Paul Farmer; it is for each of us to find our own selves as healers at some point along the astonishing trajectory that he set out. Our capacities will vary. It is about making the radical effort that matters and will continue to matter for each of us who define purpose in our lives through seeking to do the hard work of global health delivery.

Paul Farmer's monument, which is worthy of the extraordinary healer it memorializes, is in the everyday work of Partners In Health and the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine he led at Harvard Medical School to teach, model, and sustain the reality and spirit of accompaniment. That revolutionary idea and its power to transform our practice can change our world if only we have the courage to match Farmer's enduring example with our own commitment and the meaning it brings to us and those we care for.