As nations around the world have expanded access to reproductive health services, the quality, accessibility, and safety of abortion care has improved, as has maternal health. International authorities have called abortion a crucial aspect of health care.

Still, opposition to abortion remains strong in parts of the world, especially in the United States. When the United States overturned the right to abortion in 2022, the ruling rattled the nation. Yet the moment spoke to the country's paradoxical and pendulous history with abortion. Even though the United States permitted the practice for decades within its own borders, it has long restricted funding for abortion care abroad.

The Supreme Court's decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization also ignited moments of worldwide reflection. Some countries lept to add fuel to an already festering anti-abortion fire; others took it as a warning to enshrine abortion protections at home.

That decision has—and could continue to—embolden action in other countries, for both those who want to roll back abortion care and those who want to protect it. As the debate rages within the United States in battleground elections and among several state courts, including Arizona, Ohio, and Texas, the rest of the world is taking stances on this health-care right.

Why It Matters, a podcast from the Council on Foreign Relations, sat down with two experts on the legal and health consequences of abortion bans around the world: Patty Skuster, scholar at the University of Pennsylvania and researcher for the World Health Organization (WHO), and Onikepe Owolabi, physician and director of international research at the Guttmacher Institute.

Their extended conversation is available to read here, and the podcast is available at Why It Matters, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube.

Access to Abortion Has Increased Globally

Most nations have become more liberal with their abortion laws over the past 30 years, but not the United States and a few others

Why It Matters: To start, why is abortion a health issue?

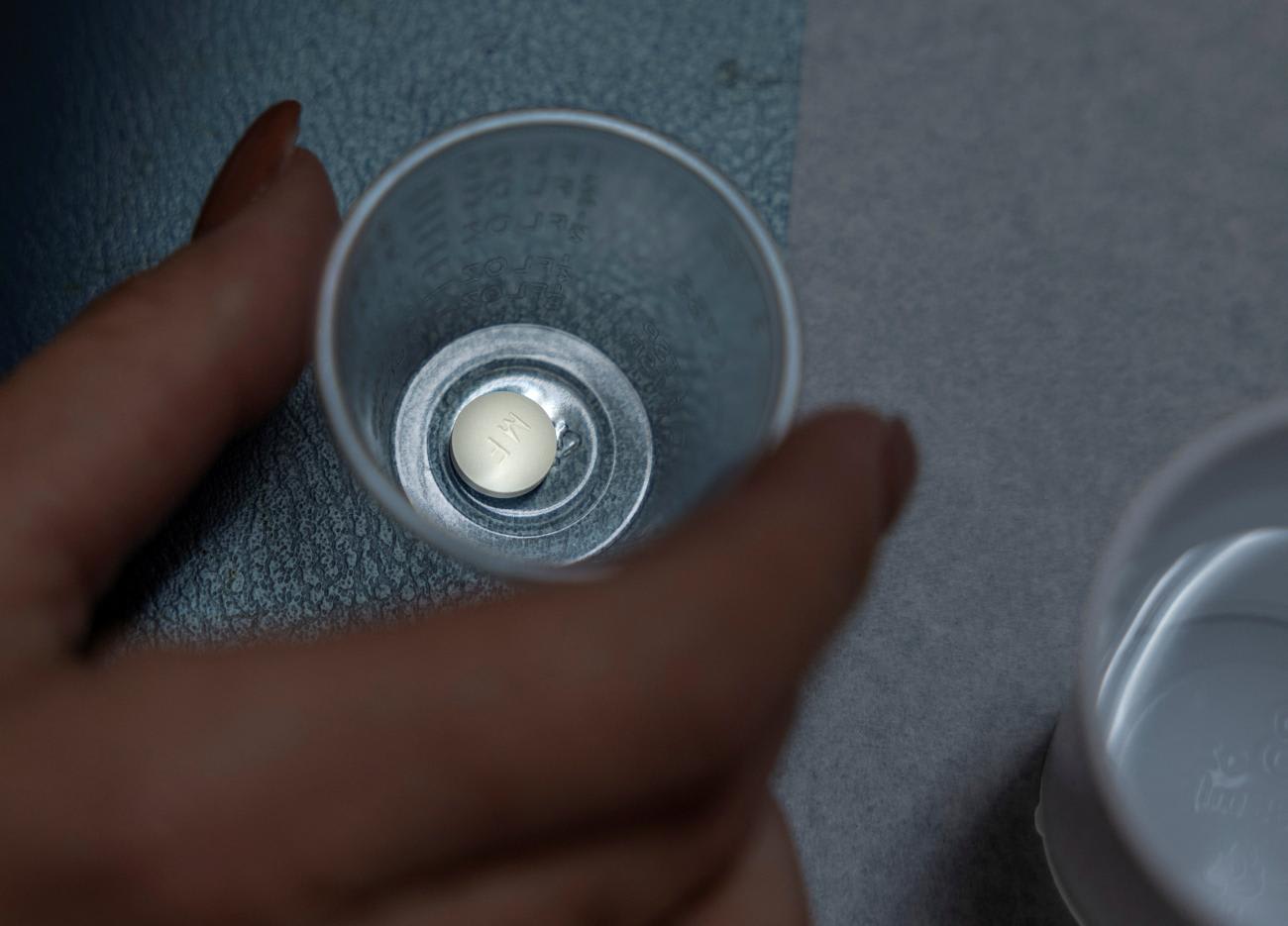

Skuster: More than 20 years ago, the WHO saw high maternal mortality rates around the world, many of them attributable to unsafe abortions. The WHO noticed that in places where abortion is highly restricted, maternal mortality rates from unsafe abortion were high. So, when the WHO makes recommendations around removing barriers to abortion, it is in service of reducing death and injury around the world and improving reproductive health outcomes.

Owolabi: Public health aims to promote and protect the health of all people and all communities, trying to avoid the adverse outcomes of decisions, infections, conditions, on people's health. Access to abortion care is essential for miscarriages, incomplete abortions, fetal death, and women who decide not to continue a pregnancy. If reproductive health really aims to ensure complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease, then abortion is a key part of the care that [doctors] should provide to women.

Why It Matters: Do these abortion bans work?

Skuster: For decades now, when you look at data around the world, you see that when abortion has been restricted by law, it hasn't necessarily reduced rates of abortion. Instead, it has sent people outside the formal health-care system to get abortions.

Owolabi: Abortions have happened for many generations. That is why all the data we have shows that abortion rates in countries where laws are restricted and in countries where laws are liberal are pretty similar. The only thing that changes is the process—and thus the woman's outcome. Even though it has been politicized, abortion is basic health care. It is sought and needed in all settings, even when it is restricted, and access to abortion ties into bodily autonomy and public health.

Why It Matters: What are the harms of such abortion bans?

Owolabi: If people are pushed to access unsafe abortions, either because they don't know where they can get access or because the context is extremely restrictive, they can experience physical health complications. The most severe of these usually are bleeding, hemorrhage, and severe infections, which we would call sepsis. In some of the most challenging contexts, damage to abdominal organs or uterine organs, which can usually result in shock and death, are possible. Increasing access to safe abortions takes away a very easily preventable cause of maternal mortality.

Skuster: When you criminalize abortion, you're really stigmatizing it, deeming it something bad, although the practice of abortion is quite common. The data from the United States says that 1 in 4 people have abortions.

Why It Matters: Is abortion thought of as medical care around the world? Have you noticed any trends in how abortion care is perceived across the places you've worked?

Skuster: The decision of Roe v. Wade was a novel argument, but we've since seen it seep into other places, including international human rights law, where the committee that oversees a treaty on civil and political rights at the United Nations started to recognize abortion as an issue of the right to privacy.

Owolabi: Changing the law does not immediately translate to access. Despite a push toward liberalization, it often takes a good amount of investing in health-care infrastructure, training health workers, and ensuring that people understand they can access safe and legal abortions to bring the country to a place where it is widely available. We also often need a lot more effort to get this care to the most marginalized, who often face the greatest risk when they can't access safe abortions, including youth, LGBTQ+ disabled people, and people in rural areas.

Why It Matters: Why has the discourse over the practice become fiercer in the last few years?

Skuster: For nearly 50 years, the United States had a constitutionally protected right to abortion under Roe v. Wade. Before viability, abortion was federally legal in the United States. [Viability, generally, is the word doctors use to describe the likelihood that a fetus survives outside the womb, which U.S. doctors estimate to occur after 24 weeks of pregnancy.]

No matter what state, that was the baseline. Then, in 2022 came the Dobbs decision, when the Supreme Court removed the right to abortion. That enabled states across the country to make abortion illegal.

Why It Matters: How does that compare with the rest of the world?

Skuster: Globally, we've seen massive, undeniable trends toward loosening restrictions on abortion, steps toward making abortion more available, and making more abortions legal. Depending on how you count it, some 60 countries in the past 30 years have made their abortion laws more liberal; only a small handful, which includes the United States, have made their abortion laws more restrictive. Looking at the trends, the United States is a decided outlier.

Owolabi: Having to deal with the Dobbs decision is challenging for people who live in the United States—and for those in countries where the impact of Dobbs is reverberating.

Why It Matters: So, Roe having established precedent for constitutional protections for abortion guided policies abroad, the Dobbs ruling to take these protections away has had the same worldwide effect?

Skuster: Another country's court system has taken a repressive stand using the reasoning in Dobbs. A Ugandan constitutional court just upheld a highly restrictive law criminalizing same-sex behavior. Highly repressive. The court actually cited Dobbs and said, "when we're interpreting our constitution like the United States, we're going to look at history and tradition."

Owolabi: We have already started to see ripple effects globally. The Dobbs decision has been cited in multiple other regressive laws, including Uganda's anti-LGBTQIA law, in Nigeria's bid to roll back the Safe Abortion Act in Lagos state, and in Kenya's refusal to push forward with the more liberal abortion law. The impact of the U.S. decisions on abortion is affecting countries globally and empowering people to make decisions that affect the human rights of women and girls all around the world.

Some 60 countries in the past 30 years have made their abortion laws more liberal

Why It Matters: Do you think in these movements on abortion and other rights restrictions would've been different without the Dobbs ruling?

Skuster: It wouldn't have been a different decision necessarily, but that constitutional analysis is being picked up to repress certain groups of people, sexual minorities in this case, is troubling. Seeing it picked up around the world is not the direction of freedom.

Owolabi: I do think that the United States has global significance. For a while, I wondered how big the impact of the decisions taken here would be on other countries, and now we have seen, since the Dobbs decision, that it is considerable.

Why It Matters: So perhaps it's fair to say that decisions like Dobbs are at least politically useful for leaders around the world who are seeking to block abortion access in their countries.

Skuster: Yes. It's putting a decidedly influential tool in the toolbox of repressive regimes. Judges and justices can and often do look to other courts in deciding law. I've seen it firsthand in drafting legislation. Legislators might deliberately look around the world. Judges do the same thing, explicitly or otherwise. It's not that unusual, but to directly cite Dobbs and to use the same analysis in that robust way certainly is.

Owolabi: We will likely continue to see ripples from Dobbs because the United States has established itself as a influential country. The impact is likely to be felt in all low-income countries, such as those in South America, which have been highly successful with the Green Wave movement. Many of those countries are now in an election period, changing their governments.

Why It Matters: Knowing that the United States directs several billion dollars in foreign aid toward public health each year, would you say it has an outsized impact on global health? What role has the United States played in health policy? Has that status shifted over the years?

Skuster: The United States is the largest funder of reproductive health around the world. Its global health funding through the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) program and reproductive health funding has enabled increases and advances in global health for decades. However, Washington has had an anti-abortion global health policy since the 1973 Roe ruling. It restricted its funding to say that no foreign assistance can go to abortion. The result not only reduces the availability of funds for abortion, but also sends the message that abortion is different from other health-care services.

Owolabi: The United States funds many maternal reproductive health programs. As we've seen over time, every time something happens in U.S. domestic policy space, it affects the direct funding countries get. Those changes make the context more restrictive and reduce access to safe family planning care. They compromise the ability of the few providers brave enough to provide abortion care to do so easily.

Why It Matters: Do other governments restrict foreign aid dollars on abortion like the United States does with the Helms Amendment or the global gag rule that prohibits foreign funds from going toward abortion care?

Skuster: The United States is the only donor government that has an explicit restriction on funding for abortion. That's not to say that every government funds abortion, but Washington is the only one that restricts funding abortion. Carving out abortion, which is a key part of reproductive health, not only has a considerable impact on global health programming, but also reinforces abortion stigma.

Owolabi: If support for development aid changes and the global gag rule is reinstated, it ultimately affects the willingness of many organizations that support reproductive care delivery to discuss abortion in any form, often their willingness to sometimes even provide family planning.

[The Helms Amendment is a 1973 law that prohibits countries from using U.S. aid to fund abortions or related research. The Mexico City policy, also known as the global gag rule, goes further, requiring foreign nongovernmental organizations to certify that they would not "perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning" with funds from any source—including from outside the United States—as a condition of receiving U.S. government global family planning funding.]

Why It Matters: The connections between the U.S. rollback and other groups abroad capitalizing on the anti-abortion resurgence are clear. Have any countries had the opposite reaction and cemented protections?

Skuster: France just had a popular vote overwhelmingly in favor of abortion. Abortion was legal in France before, but this time the French people said, "let's change the constitution and make abortion a right." What happened in France was directly spurred by Dobbs.

We're seeing similar votes in U.S. states where, when given the opportunity for a population to vote on the constitutionality of abortion, even in conservative states, the popular vote supports abortion rights. [Six states have held votes on abortion-related constitutional amendment measures since the Dobbs decision, and up to 15 could hold similar votes in 2024].

When abortion laws are changed and more women have access, reductions in some of the worst outcomes of unsafe abortion follow

Owolabi: In the past few years, we've made a lot of progress on abortion law from a legal perspective. Evidence from countries in Latin America, including Mexico, and others such as Nepal, where abortion law has been liberalized, suggests clearly that when abortion laws are changed and more women have access, reductions in some of the worst outcomes of unsafe abortion follow. In fact, if you look at some of the evidence from Southeast Asia, you don't see just severe complications of abortions drop, you also see maternal mortality do so dramatically. Increasing access to safe abortions takes away an easily preventable cause of maternal mortality.

Why It Matters: You mentioned the importance of voting on abortion rights, and that the United States has a domineering role on the global stage in health policy. As the United States heads into a defining election year, what are the stakes for abortion law at home and beyond borders?

Skuster: From a policy perspective, the global gag rule is of great concern. We've seen that when it is on, organizations shy away from any type of abortion work. We would expect a Trump administration to implement a global gag rule as one of its first acts. That said, the appointment of judges and justices is where I'm seeing the connections between gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, and abortion rights.

Owolabi: Whichever way it goes, it will have important implications for the rest of the world. We know from our work that if the global gag rule is reinstated, a huge panic often follows.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The responses were edited for length and clarity.