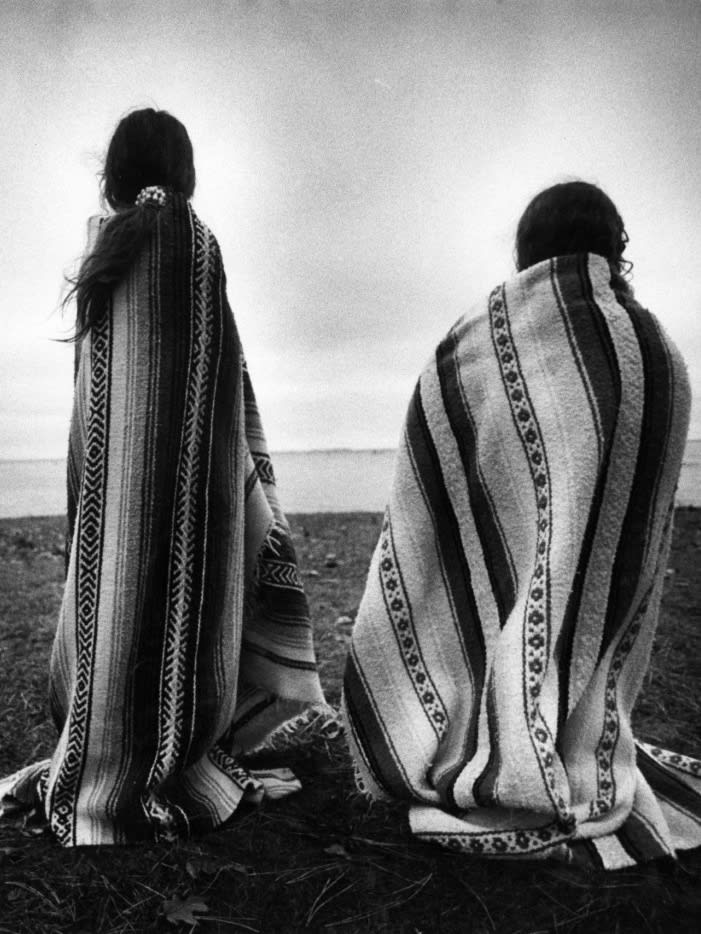

Since 1970, the National Day of Mourning (NDOM) has been observed in the United States, after Native American tribes in New England brought attention to the myths surrounding the U.S. holiday of Thanksgiving. It is a day of remembrance and protest, of honoring Native Americans who have suffered and died due to European settlement.

The observance of this day started when Wampanoag leader, Wamsutta Frank James, was set to give a speech on Thanksgiving that called out the injustices—the genocide, land theft, and poverty—that Native American's have faced since the arrival of European settlers 400 years ago.

"The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans," James said in his speech.

The event planners did not allow the Wampanoag leader to give the speech he had written, and instead of writing a new one, Wamsutta Frank James said he would not speak. Word of this spread and the Day of Mourning was created in protest. Now, on the fourth Thursday of November, many Native Americans from different tribes around the New England area gather in Cole Hill, Massachusetts, overlooking Plymouth Rock.

"NDOM is important because it corrects the historical record about what happened to Native Americans following the arrival of the Pilgrims," said Kisha James, a youth organizer with United American Indians of New England (UAINE) and one of the lead organizers of the National Day of Mourning.

An enrolled member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) and Oglala Lakota, and granddaughter of the founder of the National Day of Mourning, James said in an email, "We Native people have no reason to celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims. We want to educate people so that they understand the stories we all learned in school about the first Thanksgiving are nothing but lies."

The myth that is often told around Thanksgiving is a tale of friendship between the Native Americans and the settlers, but it stands in the place of what really happened after Thanksgiving—the erasure of the experience of Native Americans in the early 1600s and in the decades after that as more and more Europeans came to the "New World." Often, especially in school settings, a peaceful picture is painted of the event—a harvest celebration—and not much is mentioned about the Native American experience.

The National Day of Mourning is not only a day of remembrance for fallen ancestors but also a day for Indigenous people to speak out about community issues. Indigenous people today still face a multitude of challenges—including issues related to land rights, housing, health, and employment—many of which fall on deaf ears.

To this point, James shared the words of UAINE co-leader Mahtowin Munro, who said, "Indigenous solidarity and resistance are international. We stand in solidarity with the Wet'suwet'en who have been attacked by the RCMP [Royal Canadian Mounted Police] for trying to stop a destructive Coastal Gaslink pipeline, and with all those opposing pipelines and mines."

People who want to be allies of the Native American community can help bring attention to the National Day of Mourning and stand with Indigenous communities, James said.

"In terms of what allies can do to acknowledge and learn more about this day, I have a few ideas: they can take a few minutes before sitting down to Thanksgiving dinner to educate themselves and their families, tune into the NDOM livestream, read my grandfather's 1970 suppressed speech, or listen to this broadcast from NPR on NDOM," she said.

These resources could help those who would like to learn more about this day and stand with Indigenous people to remember those who suffered at the hands of European colonialism and those who are still being affected by discrimination.