The clock is ticking on the World Health Organization's target to reduce stunting in children under age five within five years—one of five overall WHO Global Nutrition Targets intended to encourage governments to tackle a key element of child growth failure. New research has identified trends both encouraging and discouraging.

Nutrition-related factors contribute to 45 percent of deaths in children-under-5—claiming about 3.1 million lives a year

Child growth failure is an umbrella term that includes stunting, wasting, and being underweight among children under five. It is often fatal, and for those that do not die early from child growth failure, the consequences are often lifelong and tragic: cognitive, physical, and metabolic impairment, creating a downward spiral of poor educational performance, low wages, lost productivity, and poorer health. With nutrition-related factors contributing to about 45 percent of deaths in children under five, claiming the lives of some 3.1 million children a year, the WHO targets seek to reduce stunting by 40 percent and wasting to less than 5 percent by 2025.

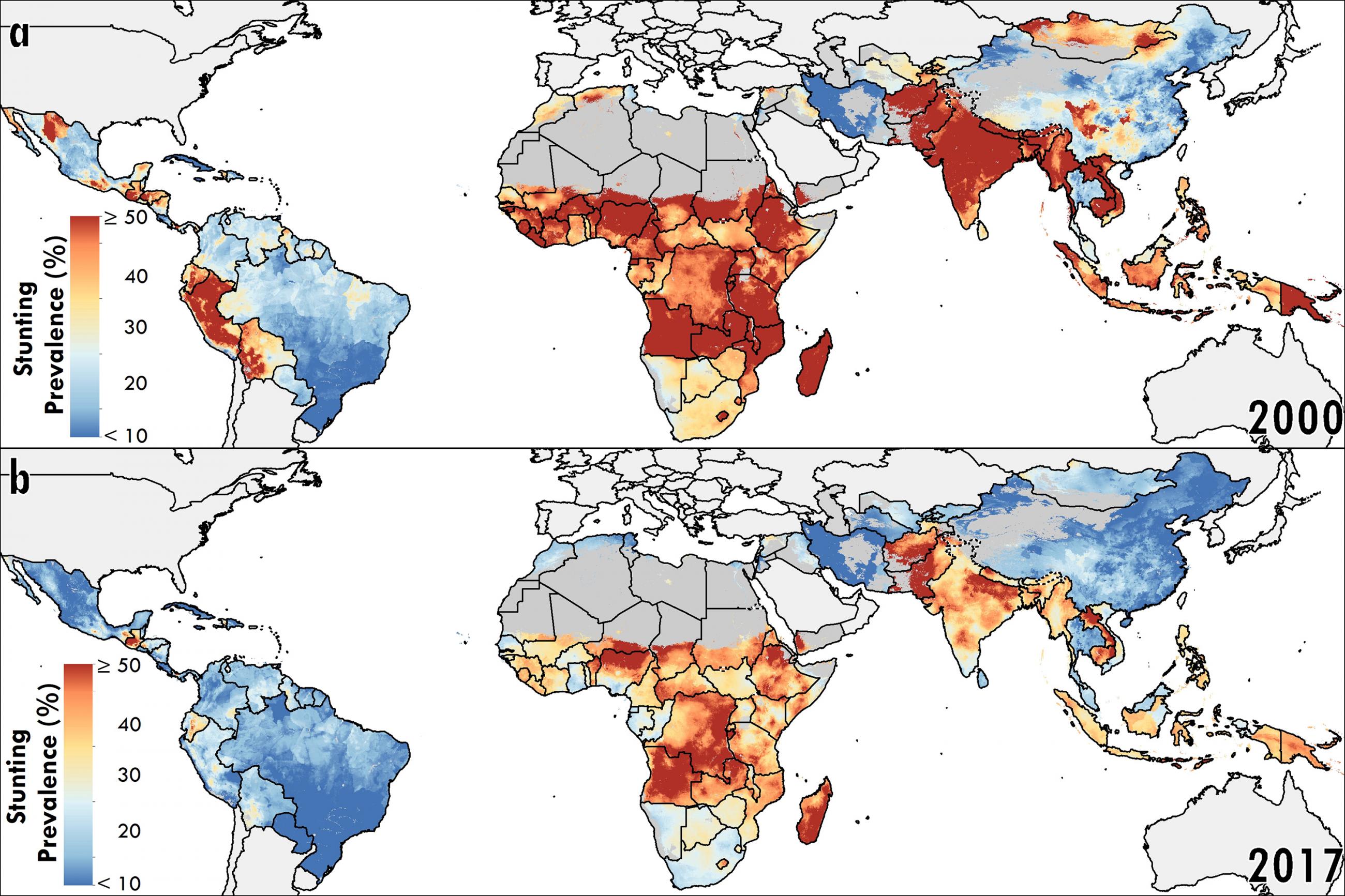

Our team of researchers at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), along with collaborators in several countries, recently found significant declines in the period 2000–2017, in both stunting and wasting across many of the 105 low- and middle-income countries surveyed, where 99 percent of children affected by child growth failure live. However, the high-spatial-resolution mapping used for the study also revealed that progress within the countries studied was inconsistent, with one in four children under five years of age still suffering from at least one type of child growth failure.

Progress was inconsistent, with one in four children under five still suffering at least one type of child growth failure

Progress toward this Global Nutrition Target was particularly noticeable in Central America, the Caribbean, and Andean South America. But even in these areas, local-level estimates revealed a stunting prevalence of at least 40 percent in central Ecuador and southern Mexico, similar to the national level for India. Northwestern Mexico, by contrast, had one of the highest levels of stunting in 2000 but one of the highest rates of decline by 2017. In Nigeria, the study found that stunting was four times as prevalent in the most affected region as it was in the least.

This leads to a simple question: When we see such inequalities, is it better to invest equally across a country, or should nations target levels of assistance where the need is greatest?

Increased efforts, particularly in densely populated areas in countries with a high prevalence of child growth failure, would likely substantially reduce this problem. However, such an approach would also risk marginalizing rural communities where the cost of progress is much greater but the need is the same—or even greater.

As our ability to create more precise maps and as our estimation techniques improve, we must question whether national targets are the most effective way to encourage countries to tackle problems of global concern that more often than not have a local dimension. While any progress towards the World Health Organization's Global Nutrition Targets is positive and to be applauded, it is important to recognize how overly generalized information can disguise disparities, which as a result may never be confronted.

So are national targets outdated?

We must seriously consider adding sub-national or local targets to the international goals set for countries

As these types of data analyses improve and become more mainstream, enabling researchers to dig down deeper, we must seriously consider adding sub-national or local targets to the international goals set for countries. These would serve as better guides for policymakers looking to spend limited resources more effectively in areas of greatest need. For example, we might stipulate that a nation decreases child growth failure by half in a certain time frame and that this feat needs to be achieved in a threshold number of districts within the nation. At the very least, this type of framing requires intentional thought about the geographical equity of intervention policies.

Child growth failure is qualitatively different from many other health problems for which we still seek "magic bullets." We know the solution: ensuring children receive adequate nutrition.

Writing in the journal Nature in 2018, former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan noted, "Nutrition is one of the best drivers of development: it sparks a virtuous cycle of social-economic improvements, such as increasing access to education and employment."

As Annan observed, the cost is not just to the individual child, but also their family, their community, and their country. Child growth failure is more than just the failure of children under five years of age to develop in line with WHO standards. It's also the failure of the entire global community to build infrastructure and systems resilient enough to distribute food to everyone who needs it.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors are employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which leads the Global Burden of Disease Study. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual authors and are not necessarily shared by their institutions.