As the world quietly passes the six-month anniversary of the World Health Organization designation of the novel coronavirus as a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC), it’s hardly news that COVID-19 has impacted some countries much more than others. Where the United States has seen an estimated three million cases and 130,000 deaths through early July, South Korea—another wealthy, technologically advanced country with a large urban population—has had fewer than 300 COVID-19 deaths.

Scandinavian neighbors Sweden and Norway have had vastly different experiences of COVID-19

Additional examples of countries faring well while others struggle abound, and not just when comparing nations as different as the United States and South Korea. Despite their many similarities, the Scandinavian neighbors Sweden and Norway have had vastly different experiences of COVID-19: through July 4, according to estimates of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), where we both work, Sweden has seen more than 5,000 COVID-19 related deaths while Norway has seen fewer than 250. And while infections in Norway peaked on March 21 at an estimated 15.0 per 100,000 and have, as of July 4, gone down to 0.3, COVID-19 infections in Sweden are much higher. At their peak on April 2, infection rates were 80.4 per 100,000, and as of July 4, they stood at 15.7.

Likewise, Cuba and Brazil offer a stark contrast in COVID-19 outcomes. Both are tropical, Latin American, upper-middle-income countries (per World Bank groups), but Cuba has seen far fewer COVID-19 deaths than Brazil: 86 (0.8 per 100,000) in Cuba versus more than 63,000 (29.1 per 100,000) in Brazil, through July 4. Brazil now has one of the highest rates of COVID-19 deaths in the world, its president disclosed this week he has contracted the virus, and sadly the pandemic’s toll on the country is only projected to rise.

Three strategies that have led to success: mask use, testing, and decisive action and communication

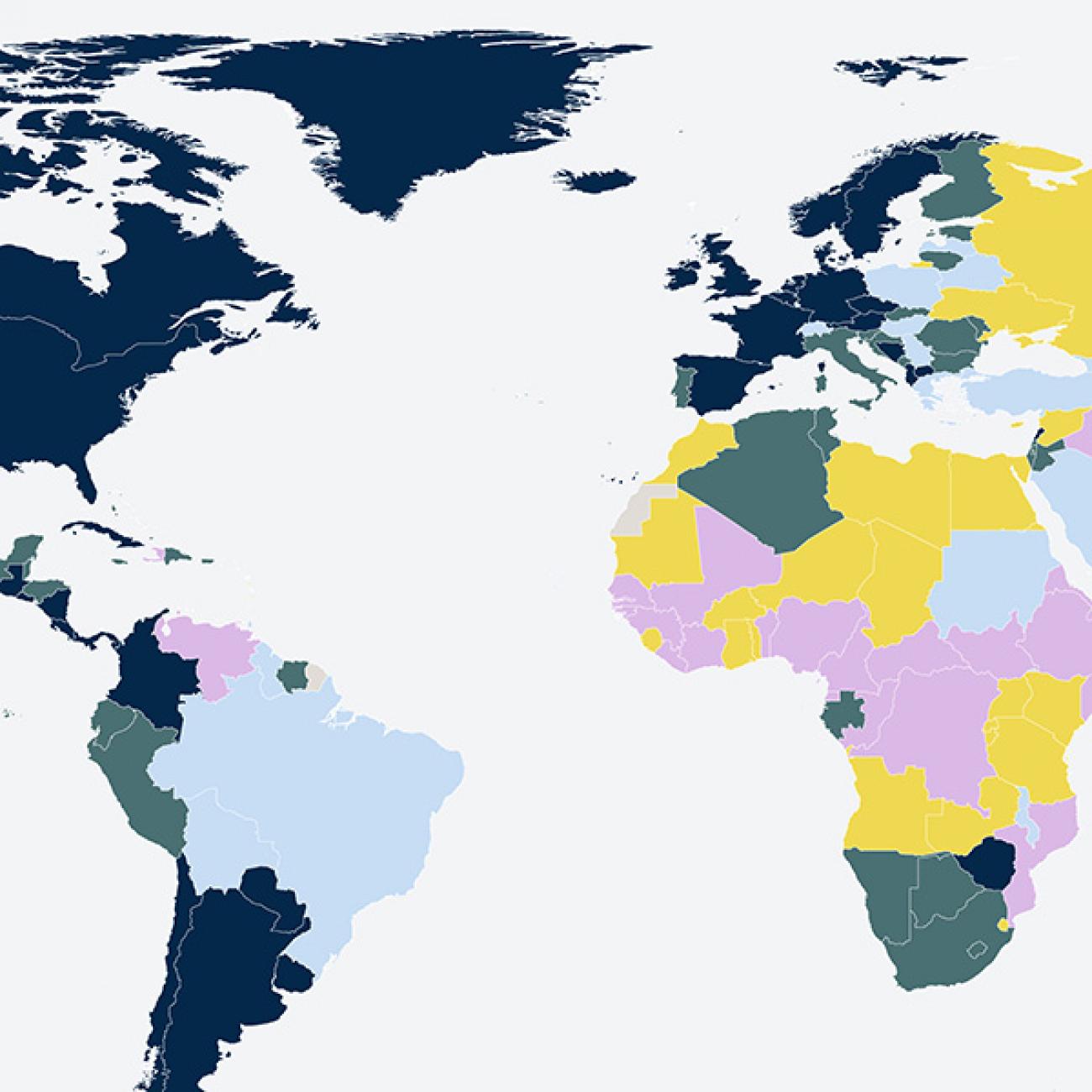

And on and on it goes. Why is there a higher rate of COVID-19 deaths projected in Mexico than in Turkey? Why, through July 4, has Ukraine seen fewer infections and deaths than several of its neighboring countries? Why have sub-Saharan African countries like Botswana and Uganda seen little impact from COVID-19 to date? Are the data lacking? If not, what are the keys to success in the fight against COVID-19? Absent the deus ex machina of a vaccine, how can policymakers turn the tide against the pandemic? So far, available evidence points to three strategies that have led to success: mask use, testing, and decisive action and communication.

Assessing the Evidence: What’s Working?

To answer the question of how to mitigate COVID-19’s impact, we can turn to epidemiological data accrued since the beginning of the pandemic, as well as success stories from countries where COVID-19 has been kept at bay. Both sources of information offer key lessons on lessening COVID-19’s impact.

Wearing a simple cloth or paper mask can reduce the risk of contracting COVID-19 by a third or more

First, mask usage estimates offer an initial lesson, because one of the best ways to mitigate an infectious disease’s impact is to prevent it from spreading. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis by IHME researchers showed that wearing a simple cloth or paper mask can reduce the risk of contracting COVID-19 by a third or more. Furthermore, a number of countries that have seen success against COVID-19 had high rates of mask use (i.e., whether or not they always wore a mask when going out) as early as April 26: 73.7 percent of people in South Korea, 69.4 percent in Japan, and 76.8 percent in Poland. By November 1, 2020, 0.55, 0.78, and 7.97 deaths per hundred thousand are projected in South Korea, Japan, and Poland, respectively (contrast this with the estimated 63.5 deaths per hundred thousand in the United States by November 1). So should you wear a mask? Yes, you should always wear a mask when out in public, and particularly when you’re indoors.

Another effective way to control COVID-19 is through testing and contact tracing. Both the data and real-world examples of success—in countries like Vietnam and New Zealand—back this up.

Specifically, comparing early testing estimates to current COVID-19 deaths shows the importance of testing as many people as possible, as early as possible. The table below compares IHME estimates of COVID-19 testing rates on March 5, 2020 to current estimates of total deaths (in rates and numbers). The table, which is sorted from high to low testing rates, shows an association between high rates of testing early on (in places like South Korea and Germany) and lower death rates.

The importance of efficient, broad testing can’t be understated. Without testing (specifically, early testing), health officials can’t know who’s been infected, and they can’t quarantine and treat the infected while tracing their contacts. Moreover, restricting testing to only those who are presenting symptoms can allow asymptomatic people—which a recent Annals of Internal Medicine study pegs at 40–45 percent of all COVID-19 cases—to spread the virus silently. Furthermore, testing, contact tracing, and containment all have to happen quickly, otherwise health officials can remain blind to the virus’s spread.

Vietnam has only seen 369 cases and zero deaths, astounding numbers for a country of 96.1 million people

“The only way that we will be able to understand who has the disease, who is infected and can pass it, and to do appropriate contact tracing, is to test appropriately, smartly — and as many people as we can,” said the Department of Health and Human Services’ assistant secretary Admiral Brett Giroir before the House Energy and Commerce Committee on June 23. Vietnam is a good example of how successful a targeted testing strategy can be. To date, according to Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 data, Vietnam has only seen 369 cases and zero deaths, astounding numbers for a country of 96.1 million people. The key in Vietnam was its early “drastic actions,” according to experts. When the virus was first detected, the government imposed travel restrictions, closely monitored and eventually closed its border with China, and increased health checks at its borders and other potential hot spots. Additionally, quarantines for visitors and those who’d come into contact with people who were infected were implemented. Ultimately, the government’s strategy of using “localized containment” has “meant that Vietnam has not done a huge amount of testing in the wider community.”

Meanwhile, New Zealand’s experience of COVID-19 is similar to Vietnam’s, and it highlights what might be the best way to combat COVID-19: decisive action and strong communication from government at an early stage.

Strong, decisive, and clearly communicated action on the part of policymakers allows for widespread testing and adoption of control measures

Starting March 23, only a month after the country’s first case was discovered, the country pursued a strategy of eliminating the virus, as opposed to simply containing its spread. The government enacted “a strict national lockdown when it only had 102 cases and zero deaths,” wrote Sophie Cousins in The Lancet. Notably, the strong early lockdown “allowed the country to get key systems up and running to effectively manage borders, and do contact tracing, testing, and surveillance,” Cousins noted. This bears repeating: strong, decisive, and clearly communicated action on the part of policymakers allows for widespread testing and encourages populations to adopt control measures such as social distancing and mask usage. After all, New Zealand has so far proven that taking this approach works: according to IHME’s July 4 COVID-19 estimates, there have been approximately 1538 infections and only 23 deaths in the country. The challenge now for New Zealand and countries in similar circumstances will be to sustain their successes while working to reopen their economies and societies, and to return to “normal” life without allowing a new outbreak to take hold.

Looking Ahead: Flattening the Pandemic’s Second Wave and Supporting Low- and Middle-Income Countries

While many other reasons for COVID-19’s uneven burden across the world have been considered—could countries’ form of government matter? Isn’t it interesting that women leaders, who have indeed taken decisive action coupled with empathetic, confidence-inspiring communication, have had so much success in mitigating the pandemic? Could island nations, with their less porous natural borders, be at an advantage, or certain disadvantages? What can analyzing the burden of COVID-19 comorbidities on populations tell us?—there remain many known unknowns about the pandemic. So in the absence of data that suggest new approaches, and pending the arrival of a vaccine, decision-makers can focus on what we do know: masks can prevent COVID-19’s spread, smart testing and contact tracing help officials isolate and track outbreaks, and action and communication can give governments time to get ahead of the pandemic’s spread.

Concerns that the lockdown would do more harm than good (due to economic hardship, food insecurity, and disrupted treatment services

These lessons may be especially helpful for low- and middle-income countries still in early the stages of the pandemic. After all, because they may lack the resources to ramp up testing and hospital resources, responding to the pandemic could prove difficult. And how can countries lock down their economies when doing so could lead to irreversible economic damage and the possibility of harm from the threat of food insecurity? The case of Malawi is illustrative: a landlocked country of 17.2 million people, according to the World Bank Malawi has a GDP per capita of 7.1 billion, among the lowest in the world. As Allison Daniel and Fanuel Meckson Bickton note in a recent Think Global Health article about the country’s experience of COVID-19, Malawi “is the only country in the world to announce a lockdown, and then cancel it before the restrictions came into force.” In short, concerns that the lockdown would do more harm than good (due to economic hardship, food insecurity, and disrupted treatment services for diseases like HIV/AIDS and TB) led to public resistance against the lockdown.

Though Malawi is due to receive COVID-19 support from the World Bank, and the United Nations published an emergency appeal for support for Malawi on May 2, Malawi’s position underscores the giant challenges facing countries with limited economic resources.

The world won’t be free of COVID-19 soon

Meanwhile, COVID-19 continues to march across the globe, causing outbreaks in new locations and returning to places that may have thought the worst was past. It seems hard to believe that COVID-19 was only declared a public health emergency six months ago—and only four months since the World Health Organization officially recognized it as a pandemic. While much remains uncertain, we do know that the world won’t be free of COVID-19 soon. As policymakers tailor their countries’ responses to COVID-19, helping lower income countries like Malawi survive (and thrive) during the pandemic should be on every nation’s agenda.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors are employed by the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which produced the COVID-19 forecasts described in this article. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual authors and are not necessarily shared by their institution.