We live in an interconnected world. A disease anywhere can be a disease everywhere. With present-day travel technologies and patterns, infectious diseases can spread from a remote village in Africa or Asia into a large urban center and then to the rest of the world—including the United States—in a matter of hours.

If for no other reason, the direct and tangible impact on the United States should make maintaining U.S. support for global health a compelling argument. The U.S. government, however, has decided to reduce its global health activities in ways that threaten U.S. national interests.

Global Health Collaboration and Assistance

The term global health covers a lot of ground. At its most basic, it refers to treating and preventing a daunting array of infectious diseases, including vaccine-preventable illnesses, vector-borne diseases, and emerging and reemerging infections. Global health also includes strengthening health systems through workforce development and training, improving laboratory systems, and enhancing public health surveillance. Those and other global health actions contribute to policy efforts on economic growth, health equity, human rights, and national and global security.

A disease anywhere can be a disease everywhere

Those objectives can be achieved through collaborative program implementation, research, and education across borders. Without intentional and consistent international collaboration, global health activities are at risk of collapsing, which would have serious national and global security consequences.

The Consequences of U.S. Global Health Aid Cuts

The sudden—and in many cases permanent—cessation of U.S. global health aid has caused a startling number of health programs and initiatives to halt field operations, unsure if, when, or how they will be able to resume providing desperately needed medicines and services. Many of the cut or discontinued programs have proven track records of success, including projects addressing HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and neglected tropical diseases, such as river blindness and trachoma.

As vice president of health programs at The Carter Center—founded by former President and First Lady Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, who believed that health is a human right—global health has been my primary focus, so the severe cuts in U.S. assistance feel tangible to me.

Not having resources for global health can result in limited access to basic health-care services, higher rates of preventable diseases, increased maternal and infant mortality, and an inability to manage chronic conditions, particularly in low- or middle-income countries. The lack of funding results in insufficient infrastructure, a shortage of health-care workers, and the absence of essential medications. That situation exacerbates health inequalities and hinders social progress, leaving the most marginalized people vulnerable to radicalization.

Global Health and U.S. National Interests

Investing in global health constitutes a tiny fraction of U.S. government spending, but its value is immeasurable. It protects people everywhere, including in the United States, from communicable diseases. It builds trust and goodwill with governments and their citizens and creates an environment for economic growth, stability, and peace.

As cynical as it could seem to some observers, health-related aid has long bolstered U.S. diplomacy. Mothers whose children are saved by immunizations provided through U.S. assistance will always remember. Conversely, if your child dies of AIDS because the U.S. government stopped supplying HIV medicine, you will never forget.

Put plainly, U.S. national interests are advanced when people in other countries see Americans as kind and generous benefactors. Whether the subject is commerce, education, health, or political development, collaboration strengthens ties between nations, increases U.S. influence, and reduces the chances of armed conflict.

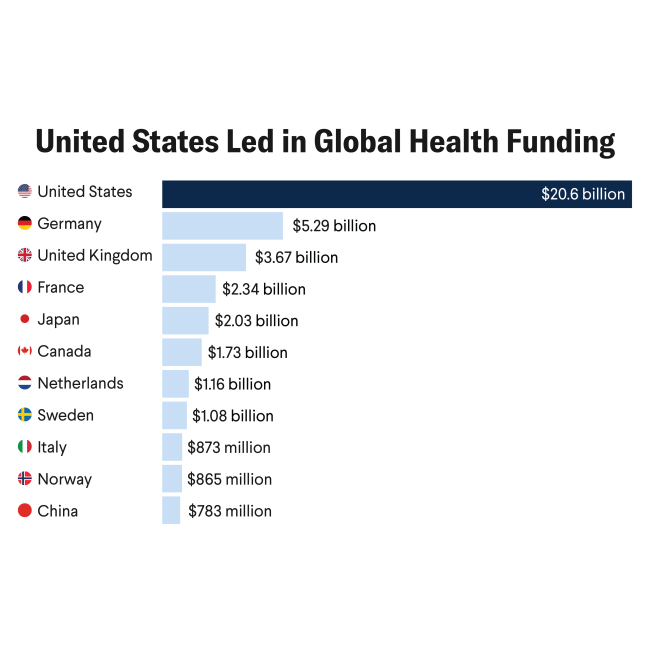

Pulling back from global health cooperation, however, hurts U.S. interests by creating a void that can be filled by rivals, such as China, which has been winning hearts and minds for years with its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative to build infrastructure in nonaligned nations.

Research and the Carter Center's experience on the ground have demonstrated that access to adequate public health resources, as well as building community engagement and trust, supports the reduction of violence and durability of peace in a region. Localized conflicts can become regional, engulfing U.S. allies and threatening the supply chains of raw materials needed to manufacture the consumer goods that fuel the U.S. economy. A laissez-faire approach to global health is simply bad economic policy.

Withdrawing from global health leadership is also short sighted for the health of Americans and citizens of other highly developed nations. An asymptomatic patient on a plane can travel almost anywhere within a day, exposing vulnerable populations to virulent microbes.

Consider the Ebola virus. If Ebola is not controlled and contained at its point of origin in central Africa, cases of the lethal hemorrhagic fever will start showing up in the United States. The U.S. population, having rarely been exposed to the Ebola pathogen, has little or no natural immunity. Even in a best-case scenario, a small outbreak in the United States could cause an economic downturn akin to that COVID-19 caused. In the worst case, an Ebola epidemic in the United States would make the devastating influenza pandemic of 1918 look like child's play.

Penny Wise, Public Health Prudent

Saving the hard-earned tax money of Americans from being wasted is a worthy goal. All governments should be fiscally responsible. But gutting support for global health is counterproductive to U.S. national interests at best, and an invitation to disaster at worst.

President Carter was rightfully admired for his lifelong efforts to help the least powerful and most marginalized. He also cared about government efficiency. He successfully balanced both goals because he understood that the world is interconnected.

"Whether the borders that divide us are picket fences or national boundaries," he once said, "we are all neighbors in a global community."