It's 2 p.m. on a Tuesday, and Shameema De La Cruz is still waiting for her 18-month daughter, who has asthma and eczema, to be seen at the Retreat Community Health Centre in a suburb of Cape Town, South Africa.

"It's ridiculous," says the former hair stylist, who says she arrived two hours early for an appointment scheduled for 9 a.m. Dozens of doctors work within a 1-mile radius of the health center and could see De La Cruz more quickly. She knows she'd be "in and out" at nearby private clinics. But she can't afford it, having stopped working two months ago to look after her ailing daughter. At the center, services are free at the point of care.

"So I wait here in this queue along with everyone else," she says.

De La Cruz's experience is common in South Africa, where a dilapidated tax-funded health service caters to 85% of the population but accounts for only just under half the country's health spending. Nearly as much flows through the country's private health service, which serves 15% of the population and offers much better facilities, shorter wait times, and more specialists. For example, 80% of the country's 200 specialist radiation oncologists work in the private sector.

On May 15, President Cyril Ramaphosa signed a law, decades in the making, to address this unfair allocation of resources by pooling all South Africa's health expenditure into one government-controlled pot. A mere two weeks later, though, his African National Congress (ANC) party suffered a humbling 17-percentage point slide at the polls to just over 40% of the vote, putting an end to the ANC's 30-year majority rule.

The election outcome is likely to pose challenges to the implementation of this new National Health Insurance (NHI) law, especially given that the ANC now relies on political allies—some of which oppose the law—to govern.

On June 30, Ramaphosa appointed Aaron Motsoaledi, health minister from 2009 to 2019, back to that role, ensuring pro-NHI leadership in the department that will oversee its implementation. Motsoaledi's deputy is Joe Phaahla, the most recent health minister and another staunch backer of the legislation.

But with just four of the 11 parties that make up Ramaphosa's coalition government backing the NHI in their pre-election manifestos, and with legal challenges against the law under way, experts believe that the NHI faces an uncertain future.

"We now have a dramatically different political reality," says Helen Schneider, who holds a chair in health governance at the University of the Western Cape. "We can expect action on a range of fronts, but the direction is very uncertain."

The rationale behind the NHI is to centralize the considerable funds that South Africa already spends on health care in a pot that's available for all.

The rationale behind the NHI is to centralize the considerable funds that South Africa already spends on health care in a pot that's available for all

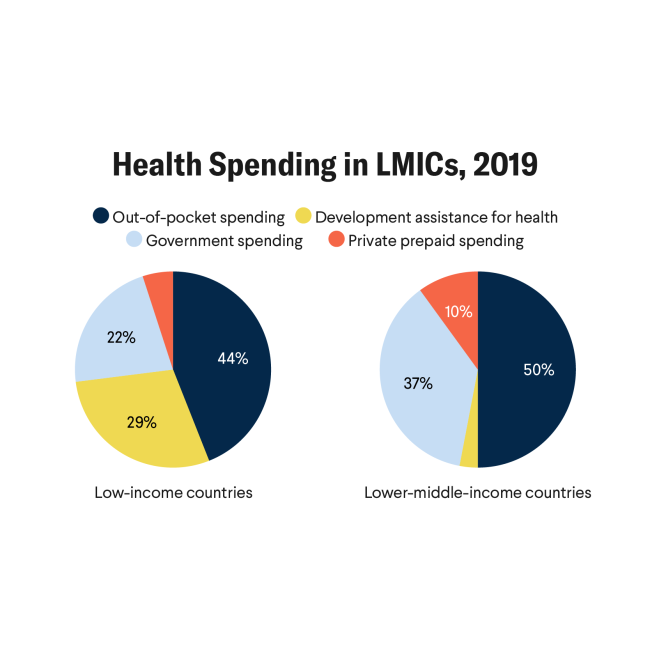

"South Africa, just looking at the public health system, is doing relatively well in relation to global norms," says Schneider. Out-of-pocket payments, for instance, account for less than 6% of the country's health spending, whereas in India, another middle-income country, they make up nearly half. In the United States, the figure is 10%.

At 8.27% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2021, South Africa's health spending also sits comfortably above the 5% of GDP that international bodies set as the minimum a country needs to progress toward universal health coverage. But per capita expenditure in 2019 was just 4,667 rands ($253) in the public sector, but 22,891 rands ($1,242) in the private sector, Schneider says. "That produces outcomes that are lower than countries with equivalent public-sector expenditure."

The NHI will create an NHI Fund, out of which the government will pay for all medical care in South Africa at a set rate. Services in both public and private facilities will be free at the point of care—and funded by general taxes as well as by mandatory contributions from employers and wage-earners proportional to their income. This plan will leverage the hundreds of billions of rands that employers and private individuals pay into private medical schemes to access private health care. Once the NHI is fully operational, such schemes will only be allowed to offer services not covered by the NHI.

"What the South African government is trying to do is very ambitious, very aggressive, very relevant, and needed," says Vishal Brijlal, senior country advisor for the Clinton Health Access Initiative, a nonprofit set up in 2002 to improve access to health care in low- and middle-income countries. But this ambition is also a key source of opposition, he says.

Private medical schemes oppose the NHI because it will greatly curtail the space in which they can operate. Several court challenges by health professions unions and private schemes are under way already, and more are expected. Some fear that the scheme will spark an exodus of medical professionals from the country.

Affordability is another stumbling block, Schneider says. Weighed down by a sputtering economy hamstrung by electricity constraints and flagging investment, South Africa's government is having to cut its budgets for the first time since the ANC came to power, she notes: "There's very little fiscal space for expanding budgets and funding towards health."

Several questions also remain about exactly how the NHI will function: Precisely what services will the NHI cover? What will be the total cost to the public purse? A lack of clarity on all those details, and a perceived reluctance among the law's architects to take on board concerns raised about the NHI in public consultations, has undermined public confidence in the scheme, Schneider says.

Concern is also widespread that the NHI's single pot could provide fertile ground for corrupt deals and mismanagement in the same way that billions of rands were looted from the country's emergency funds to deal with its COVID-19 pandemic. Many who access private health care, through either individual contributions to medical schemes or employment benefits, don't trust the government to look after their money.

South Africa's incoming health minister will need to operate strategically and diplomatically to navigate the NHI's choppy waters ahead

Anja Smith

"We've moved from a racial inequity to income inequity," says Briljal, who notes that it's the rich, or the "haves," who complain the loudest. "People with insurance don't want change and don't want to share it," he says.

South Africa's incoming health minister will need to operate strategically and diplomatically to navigate the NHI's choppy waters ahead, says Anja Smith, a development economics based at Stellenbosch University and who has studied the NHI. For Motsoaledi, who has a reputation for speaking his mind, this means mending relationships with the private health sector after "villainizing" it during his last tenure as health minister, calling it a "sick" and "brutal system," Smith says.

Motsoaledi and the ANC will also need to navigate the NHI through the myriad legislative changes still required to operationalize it in the new context of coalition politics. According to Smith, this creates an opportunity for the ANC to modify aspects of the NHI law that have been widely contested, and which could secure broader buy-in into the policy.

"The question is whether they are going to grab it," she says.

Schneider believes it is unlikely that the NHI will be scrapped in its entirety.

"Even if there's a dramatic stepping back certain things will be moving forward," she says. But as the legal and political challenges to the NHI unfold, the poor continue to suffer, Briljal observes. "While we deliberate on these issues, the status quo remains, which is unequal access."