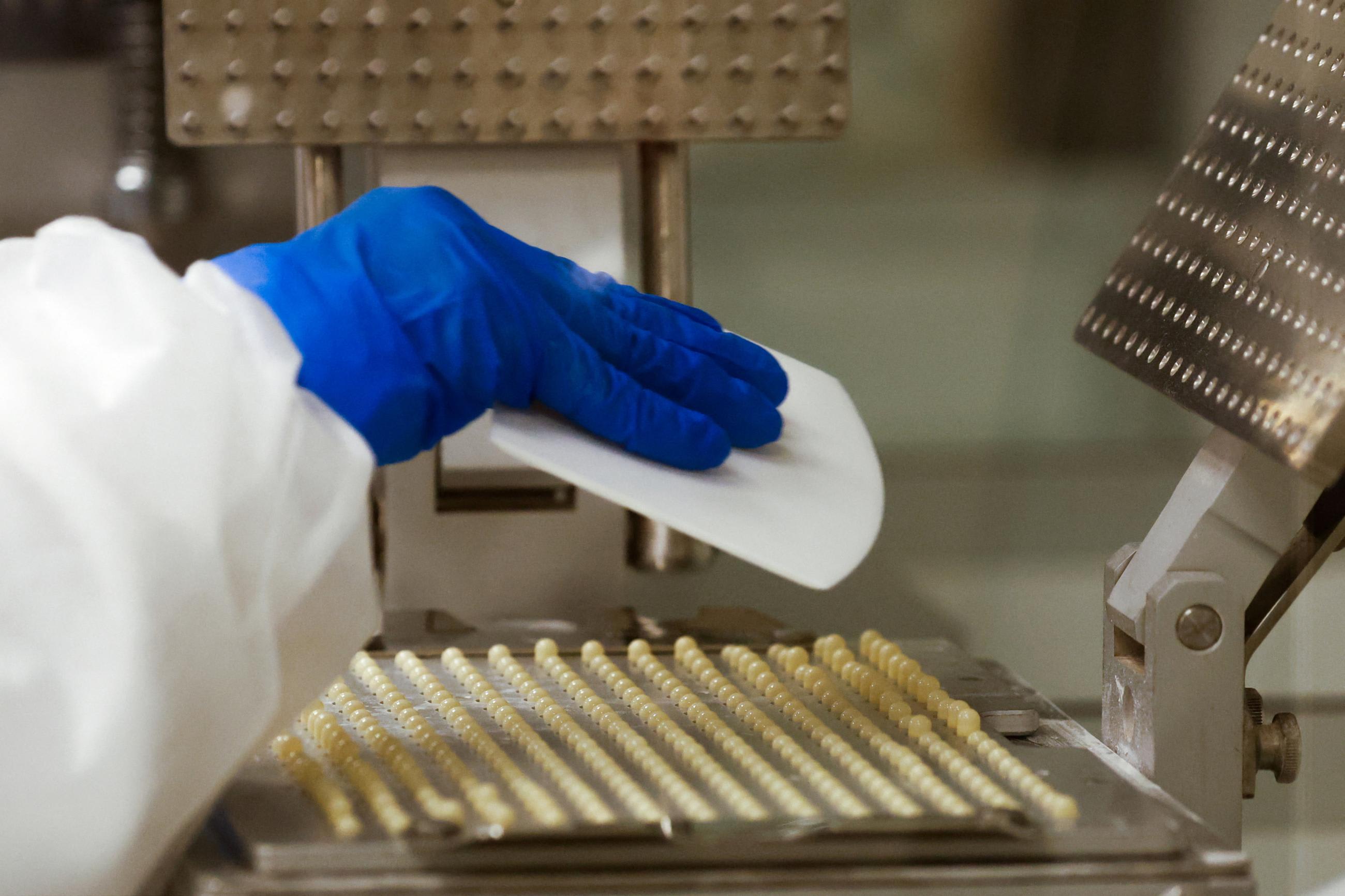

Chances are that you undergo hospitalization at some point in your life—whether because of a transplant, an organ or joint replacement, cancer chemotherapy, or an invasive surgery. Hospital procedures such as surgeries can expose a person to bacterial pathogens and thus can be performed safely only with effective antibiotics.

On September 26, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) will be the subject of a high-level meeting at the UN General Assembly (UNGA). The decision to host this discussion at the United Nations in New York rather than at the World Health Assembly in Geneva reflects the fact that AMR affects the human, animal, and environmental sectors more broadly than traditional health issues do.

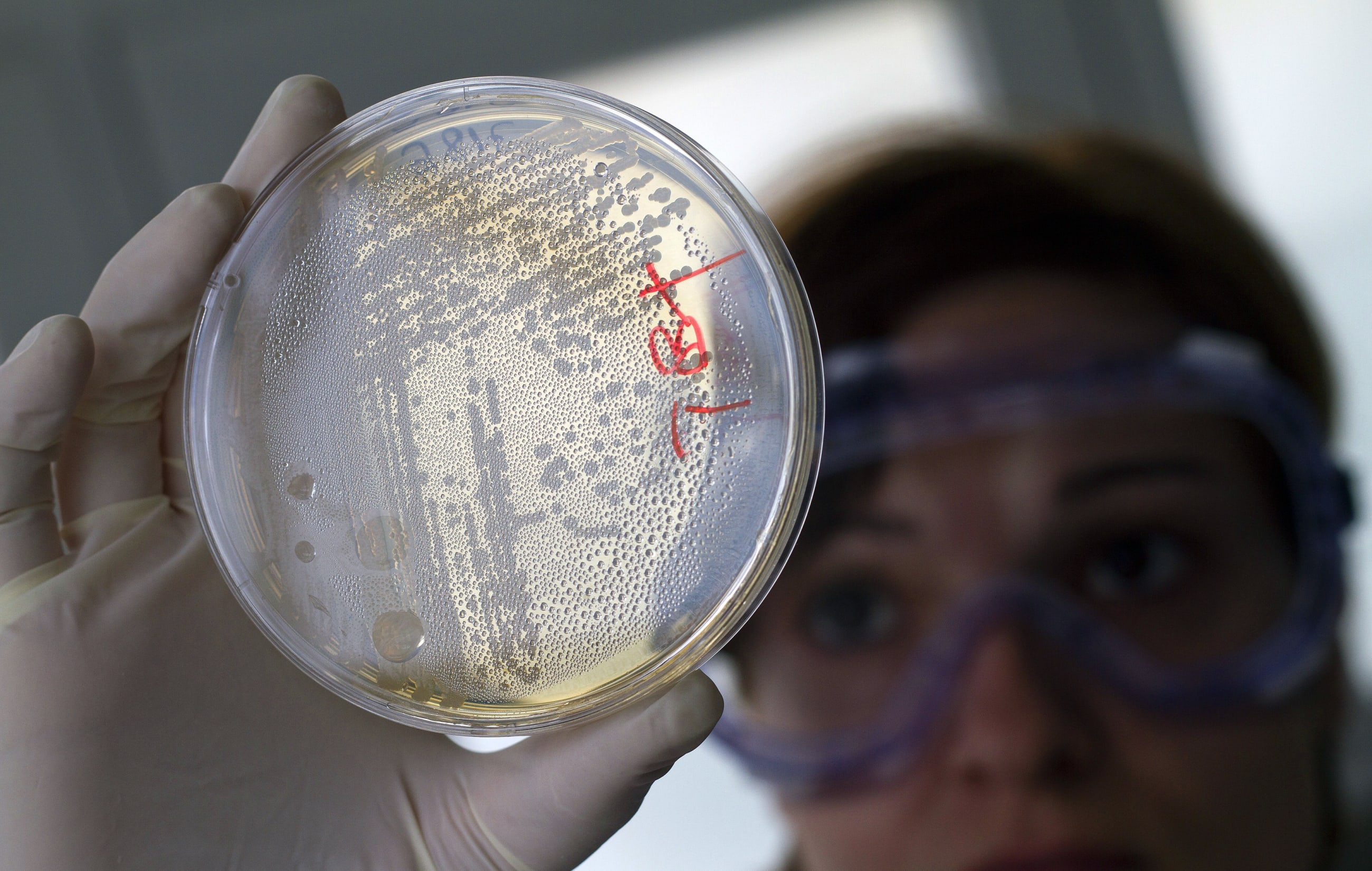

Effective antibiotics, once taken for granted, are no longer a guarantee in any country. Since they were first introduced, the hundreds of millions of tons of antibiotics used—and sometimes overused—for medicine to improve human illness, in livestock for growth promotion, and in agriculture to prevent and treat plant diseases, have resulted in the gradual accumulation of resistance genes in disease causing bacteria, leading to the ability to evade antibiotics and develop AMR.

Because humans share bacteria with animals and the environment, when and where the exposure first happened does not matter. Resistance from any source is a threat to human health everywhere.

Yet antibiotic resistance has not gotten the attention it should from public health agencies and patient groups. First, it is likely that we all know someone who suffered a difficult-to-treat bacterial infection but was unaware that it was the reason for their longer hospitalization and suffering. The term antimicrobial resistance is too technical for most audiences and the words antibiotic, antimicrobial, and resistance are not well understood among the general population.

There are 1.3 to 5 million deaths from AMR each year, vastly higher than the toll from HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis combined

Data on AMR is also lacking. Until quite recently, the human toll of AMR was poorly quantified, especially in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs), where the burden is likely to be the greatest. The best estimates put incidence in the range of 1.3 to 5 million deaths a year, vastly higher than the toll from HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis (TB) combined.

More than half of the world's infection-related deaths are caused by non-TB bacterial infections. Thus, it should come as no surprise that with the current high levels of resistance, drug-resistant bacterial infections dominate the numbers.

Compounding the rise in bacterial infections is the dwindling availability of antibiotic options for treating bacterial infections. As more companies determine that it is no longer financially sensible to produce a drug that patients are not willing to buy, fewer new drugs are entering the market.

Because most antibiotics are given over short courses, and the price per day of treatment is anchored to old expectations of low prices for products such as penicillin, companies cannot profitably sell new antibiotics. High-income countries could afford new antibiotics, but the market is too small to support new research and production, and most patients live in LMICs, where purchasing power is far weaker.

Global Goals

Efforts have been made to generate global attention to the issue of antibiotic resistance. In addition to the high-level meeting on AMR, discussions have been held to address the link between antimicrobial resistance and the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs). Increasing evidence shows that achieving SDG 3, which calls for ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages, hinges on access to effective antibiotics.

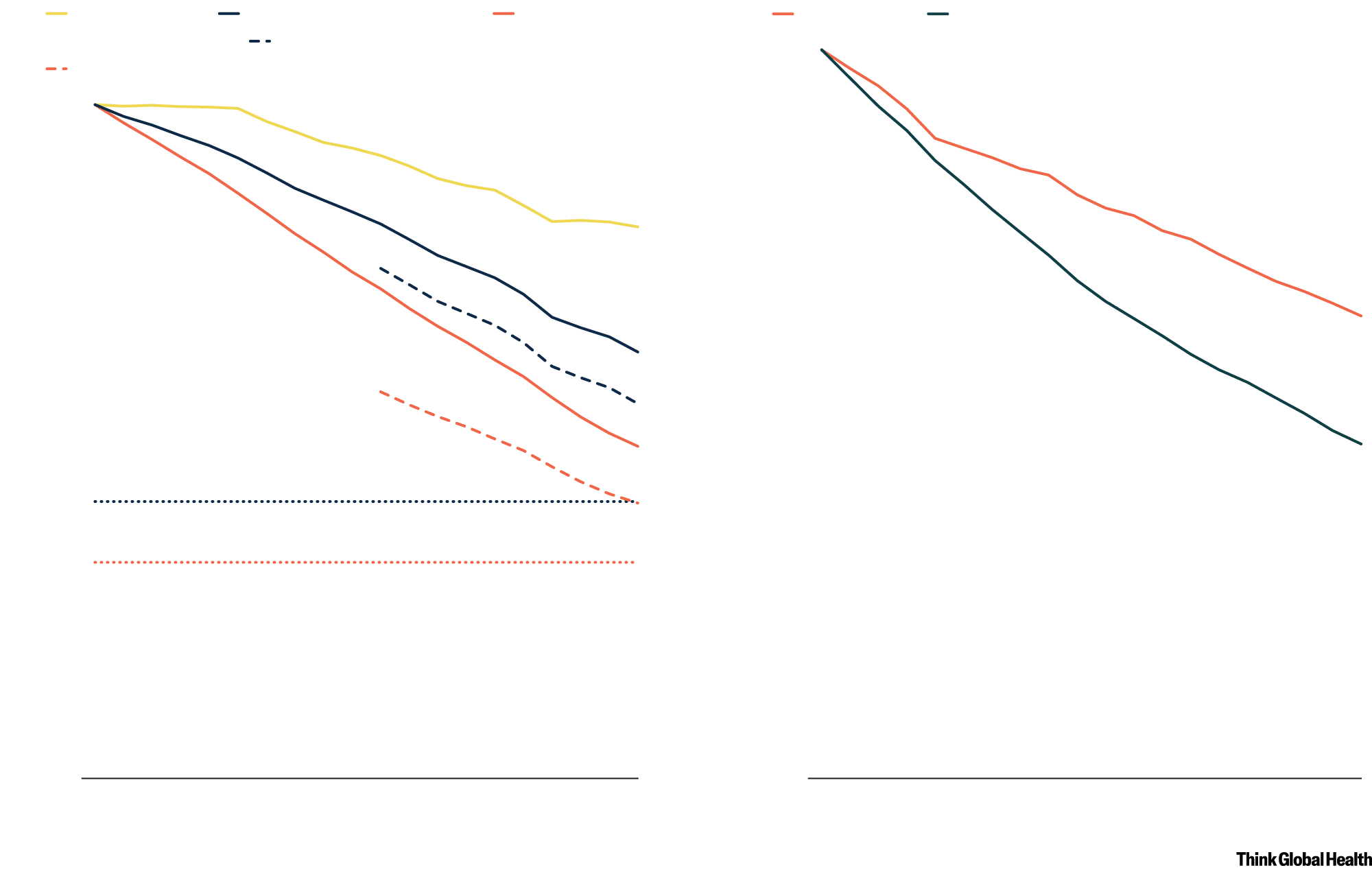

AMR Reverses Progress on Childhood Survival and Healthy Aging

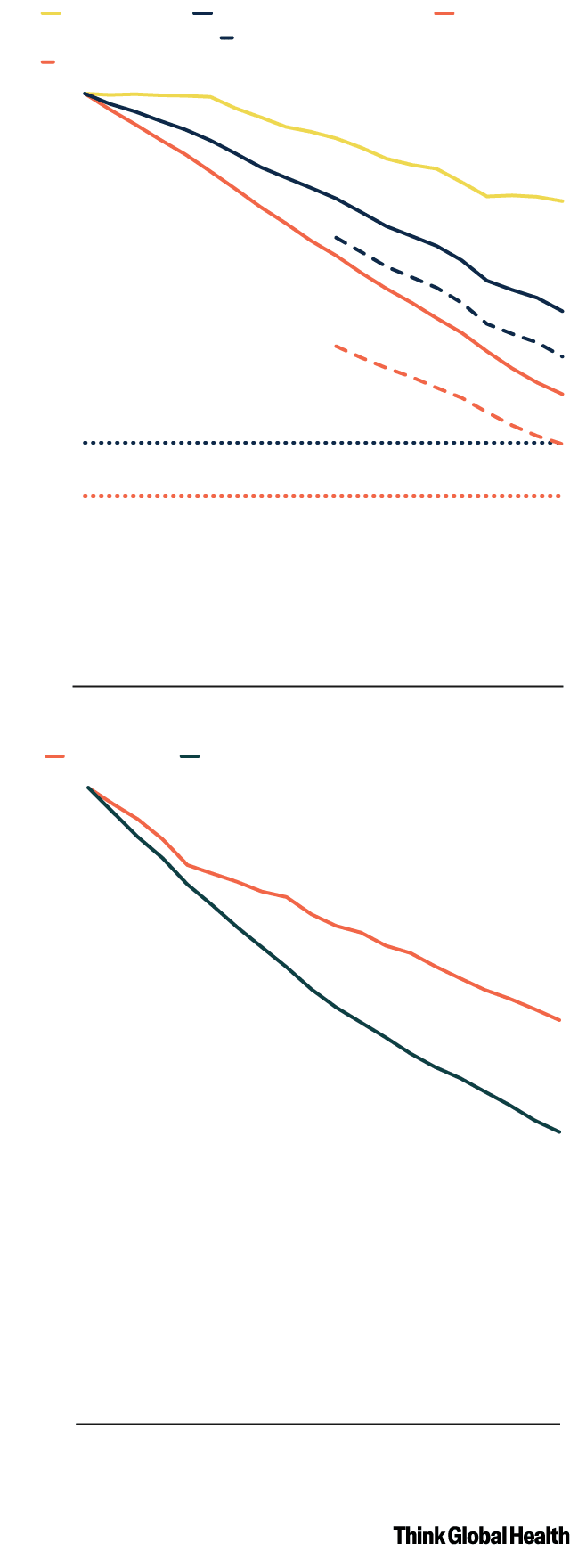

Childhood mortality rates have declined since 2000, but would be lower overall without antimicrobial resistance (AMR)

Neonatal

sepsis

Neonatal

all-cause mortality

Under-

Over

65 years

Under

65 years

5 all-cause mortality

Neonatal

mortality without AMR

100

Under-5 mortality without AMR

100

90

90

Bacteria-attributable mortality rate relative to 2000, %

80

80

Mortality rate relative to 2000, %

70

70

60

60

50

50

40

40

SDG neonatal mortality target

30

30

SDG under-5 mortality target

20

20

10

10

0

0

2000

2005

2010

2000

2005

2010

2015

2015

Chart: Adapted from the Lancet by CFR/Allison Krugman • Source: I. Okeke et al., The Lancet 403, no. 10442 (2024).

Neonatal

sepsis

Neonatal

all-cause mortality

Under-

5 all-cause mortality

Neonatal

mortality without AMR

Under-5 mortality without AMR

100

90

80

Mortality rate relative to 2000, %

70

60

50

40

SDG neonatal mortality target

30

SDG under-5 mortality target

20

10

0

2000

2005

2010

2015

Over

65 years

Under

65 years

100

90

Bacteria-attributable mortality rate relative to 2000, %

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2000

2005

2010

2015

Chart: Adapted from the Lancet by

CFR/Allison Krugman • Source: I. Okeke

et al., The Lancet 403, no. 10442 (2024).

Focusing on immunization, water and sanitation, and prevention of infection could further those SDGs while reducing the burden of resistance. Global goals on improving access to primary health and universal health coverage depend on the availability of effective antibiotics.

Finally, the global health security threat from AMR is substantial. A collapse in the effectiveness of antibiotics could come without warning and imperil entire health systems and economies. If this were to occur alongside a significant respiratory virus pandemic that causes secondary bacterial infections, the magnitude of its impact would dwarf COVID-19. That toll is high enough that nations should have an interest in working together to plan, prepare, and prevent such an occurrence.

AMR at the UNGA

The high-level meeting on AMR in 2016 resulted in a call to action, but progress since then has been limited. Across LMICs, national action plans have been formulated to tackle AMR, but most remain unfunded and therefore not acted upon. Awareness has improved among public health professionals, policymakers, and the general public about the threat posed by ineffective antibiotics, but behavior has not changed substantially. Antibiotics continue to be overused and misused in both humans and animals in many countries, though some, including the United States and Thailand, have made significant progress.

Other improvements have come from investments in new antibiotics via public private partnerships such as the Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership and the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator. Even in those instances, however, the scale of investment is not commensurate to the size of the problem. The pipeline of new antibiotics is arguably better than it was in 2016 but still not enough to address the need for affordable, effective antibiotics globally.

Access to second-line antibiotics needed when an initial course fails is highly limited across many LMICs. In those countries, more people die because of lack of access to existing antibiotics than because of drug resistance.

Although antibiotic resistance is a problem in both high- and lower-income countries, the solutions in each are quite different. High-income countries require new antibiotics to tackle infections that do not respond to most existing antibiotics. Low- or middle-income countries need greater investment in prevention (specifically in water and sanitation, immunization, and infection prevention) to reduce the load of bacterial infections and to increase access to existing antibiotics.

Herein lies the challenge: crafting a resolution that recognizes not only the importance of this problem to all nations but also that solutions may vary widely.

In low-income countries, more people die because of lack of access to existing antibiotics than because of drug resistance

The 2024 UNGA high-level meeting on AMR is expected to focus on access to effective antibiotics and prevention. Progress since 2016 has come only in areas with firm targets. Consequently, a target for 10% reduction in mortality by 2030 relative to the 2019 baseline has been included in the final declaration expected to be adopted on September 26. That target is not meant to be applied uniformly in all countries. The greatest opportunities for mortality reduction are in LMICs, where the number of deaths from lack of access to effective antibiotics is highest. Specific targets to reduce inappropriate use of antibiotics in humans and animals failed to make it to the final draft.

Another action item from the UNGA draft is the recommendation to establish an independent panel for evidence to tackle AMR. Currently, no well-funded, systematic effort is in place to share information on antibiotic resistance, consumption, or successful interventions and on policies to improve how antibiotics are used to best improve human and animal health. By way of comparison, the CGIAR system comprises institutions that permit global knowledge sharing on food and agriculture. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change plays a similar role in climate research and information sharing.

Those panels also allow for research, policy, and civil society experts to be part of global collaboration. Given the multisectoral and complex nature of the antibiotic challenge, it is unlikely that governments alone can tackle the problem. Notably, the independent panel proposed for the challenge of access to effective antibiotics was not envisaged to be an intergovernmental panel. However, significant government participation will be needed for efforts to be sustainable and effective.

Improving Access

Antimicrobial resistance has an image problem. It has been thought of as a difficult and expensive problem to resolve, and to have a small public health impact. Neither is true. Sustainable access to effective antibiotics is a critical need for humans and animals, now and in the foreseeable future. Shifting the focus from drug-resistant bacterial infections to all bacterial infections that receive inadequate treatment could help widen the set of stakeholders invested in this problem. Many bacterial infections are preventable, as current research shows.

Preserving antibiotic effectiveness—a global public good—requires political will, firm targets, accountability frameworks, and funding. A UNGA declaration, though important, is not enough to drive progress. Political will to tackle AMR needs to be developed at the national and subnational level. Targets and accountability to reach these targets need to be strengthened. Finally, funding is critical. Total global public spending on antibiotics lags behind spending on other public health priorities such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis. That needs to change. Spending on effective antibiotics needs to increase but not at the cost of other global health priorities.

For too long, the narrative on AMR has been about antibiotics being misused and therefore use needing to be reduced. Although that is true for some parts of the world, vast populations simply have too little access. The average person living in an LMIC uses half the antibiotics that a person in a high-income country does. Even that average masks significant heterogeneity in access within LMICs.

A globally funded access program for existing and new antibiotics could ensure that many deaths currently attributed to both drug-susceptible and drug-resistant infections are averted. But such a mechanism could sweeten the pot for innovators who would like to develop and bring new antibiotics to market. Today, no such pull mechanism is available to support their risk-taking in the antibiotics space.

Finally, researchers and companies need to think about alternatives to antibiotics. Bacteriophages, monoclonal antibiotics, and quorum-sensing based therapies are all in early stages and other modalities have not been adequately explored, but small molecule antibiotics that are prone to drug resistance are likely to remain the dominant treatment. To stay ahead of future bugs that evade treatments, innovation will need to leapfrog resistance.