The COVID-19 pandemic has brought into sharp relief how significant social determinants of health and health inequities affect lives and livelihoods of individuals, communities, and nations. It has laid bare inadequacies in nations' capacity to respond adequately to the emerging health, economic, and social needs of its society during a health crisis. Decades of research has highlighted the role of social determinants of health, defined by the WHO as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age (such as housing, education, welfare and work), but only limited progress has been made to impact them. Now more than ever, the challenge of addressing health disparities for vulnerable populations, whether in low or high income countries, demands innovative intersectoral collaboration on the social and economic determinants of health.

Health-care services as just one component of a multi-faceted program

Long-term debts have piled up from years of underinvestment in programs addressing social determinants of health, and these bills are now long overdue. When we look specifically at the work of the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH), a program with which we are affiliated and one of the implementing partners of Primary Care International (PCI) in Kenya, the immediate need for addressing the consequences of neglected actions are apparent. A model of care developed under this program provides health-care services as just one component of a multi-faceted program designed around the express needs of communities and individuals living in them.

The WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health highlights that these determinants are shaped by how financial resources and political powers are distributed. The social determinants of health are mostly responsible for health inequities, the preventable and avoidable differences in health access and health outcomes seen within and between populations in any settings.

Higher death rates, more devastating economic consequences, and growing inequity in society between the rich and the and poor

Recently, however, there has been a call to consider the "moral determinants of health," advocated for by Berwick as the internal conscience of doing what is right and the external action of ensuring those basic needs are met equally for all citizens. Within the COVID-19 context, the absence of solidarity in addressing the moral determinants of health means that people who are socioeconomically disadvantaged are at greater risk of COVID-19 illness and death that could otherwise have been prevented. By embracing a more "moral" approach to health, we would be forced to consider the other drivers of poor health, which continue to disproportionately impact socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. The neglect for the pervasive issues relating to social determinants of health has contributed to higher death rates, more devastating economic consequences, and growing inequity in society between the rich and the and poor.

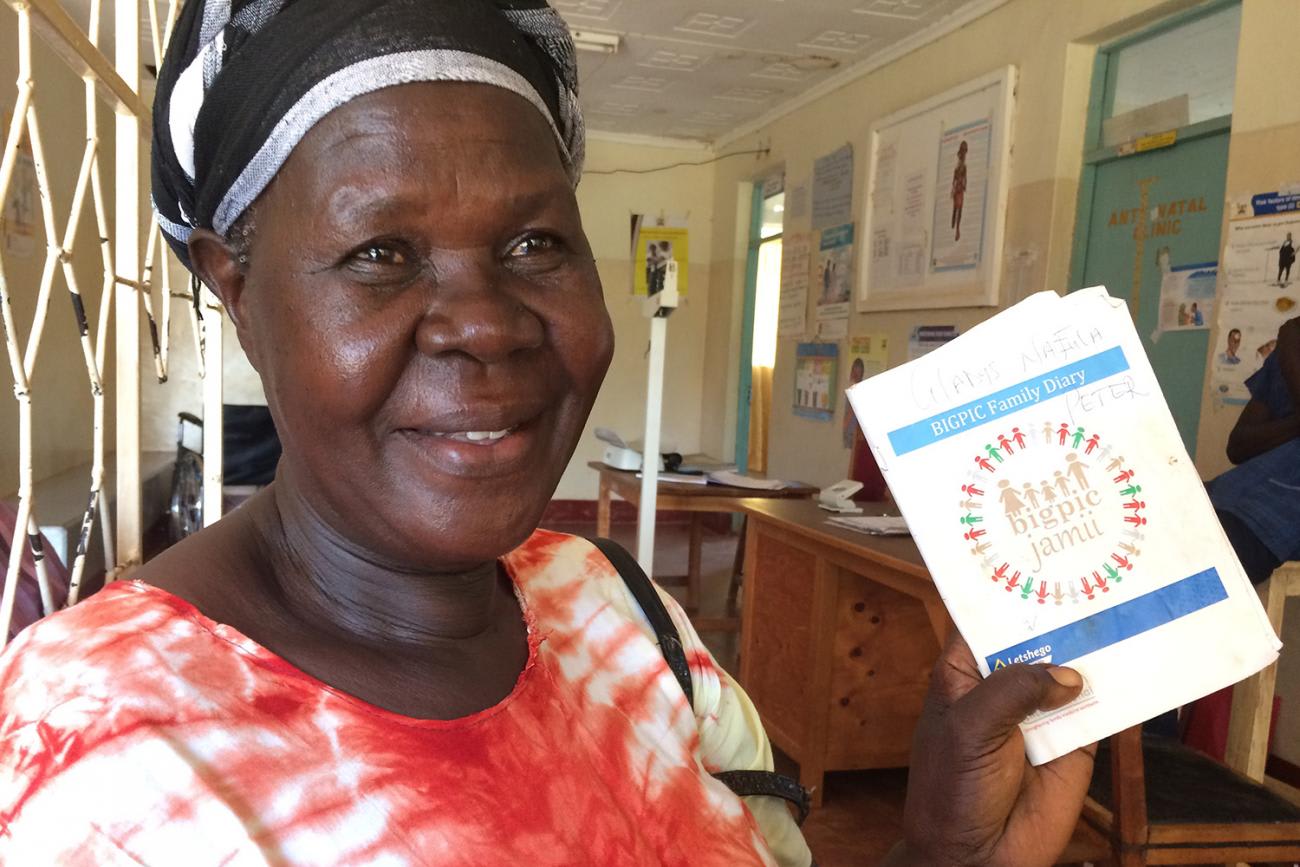

For the past decade, targeted efforts have been pioneered by the AMPATH program in Kenya to create a morally-guided care initiative to address health disparities. Through Primary Care International's collaboration with AMPATH's Bridging Income Generation through grouP Integrated Care (BIGPIC Family) program, economic needs are partially ameliorated by increasing access to capital via microfinancing, and health needs are addressed by reducing physical barriers to accessing care services for primary health-care needs.

Financial literacy training, agricultural knowledge sharing to increase productivity and efficiency, and clinical care delivery

Leveraging a contextualized and community-accepted microfinance model, the BIGPIC Family program coordinates traditional community meetings, or "baraza" in Kiswahili, to provide financial literacy training, agricultural knowledge sharing to increase productivity and efficiency, and clinical care delivery. This is done through existing microfinance groups to facilitate more convenient access to care. National health insurance enrollment is promoted for those individuals and groups who have been able to demonstrate a track record of contribution of funds to the microfinance group and loan repayment to build sustainability into the program. Two key components set this program apart from other traditional care delivery models. First, the BIGPIC Family program recognizes and intentionally ensures that barriers to care access are addressed simultaneously, rather than leaving these for the patients or someone else to worry about later.

Second, the program is premised on the belief that the family medicine approach of looking at the broad needs of the person they are providing healthcare to by considering health impacting social determinants and community factors when treating them. This model argues that this is the most optimal way to promote the incorporation of primary health-care services and health system improvements within local communities and ultimately improve population health for people living in those communities.

Addressing rapidly evolving needs in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic

While the populations participating in these models of care have been weathering considerable financial and health-care challenges, the trust we have built over many years of collaborative work in addressing social determinants of health, has enabled us to continue working with each other and continue addressing their rapidly evolving needs in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the first case of COVID-19 in Kenya on March 13, 2020, the program has been finding ways to adapt and preserve service delivery while adhering to physical distancing recommendations by the Ministry of Health of Kenya. Strategies we have implemented or are in the process of implementing are listed in the table below.

BIGPIC Family Program Strategies for Health-Care Delivery

Continuity of care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya is met through a multi-pronged approach

We hope our on-the-ground experiences coupled with research evidence can be utilized to improve and address social determinants of health and primary health-care delivery in other similar settings.

While the bill is past due, we have the opportunity to use the novel coronavirus as a wake-up call to start balancing the accounts

This example comes from Kenya, yet high income countries have not been spared either—as social unrest grips countries like the United States. While the spark that lit the fire in America was the killing of George Floyd, decades of neglect and not addressing the social determinants of health in underserved African American communities has undoubtedly played a role in the long simmering frustrations of minority communities across many settings. The AMPATH program continues to find ways to scale up services to other similarly impacted populations all the over world and in countries at all economic strata. Our goal is to clear the debts and system deficiencies, which have resulted from the neglect of social determinants of health. While the bill is past due, we have the opportunity to use the novel coronavirus as a wake-up call to start balancing the accounts. The debt collectors are waiting, and an overhaul of our approaches to health globally is long overdue to avoid defaulting on our responsibility to improve public health in an equitable fashion. Future approaches to improving health can no longer neglect these fundamental needs.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article was contributed to Think Global Health as part of Primary Care International's new Op-Ed series exploring resilient systems and healthy populations in the context of COVID-19 and beyond, which will be published in multiple venues. The perspectives of the authors are not necessarily the views of any of their institutions or affiliations.