On November 13, 2024, Balaji Jagannathan, a senior oncologist at Kalaignar Centenary Super Speciality Hospital in Tamil Nadu, a southern state of India, was brutally stabbed seven times by the son of a woman he had treated. Although severely wounded, Jagannathan survived.

The patient had been diagnosed with end-stage cancer and received six cycles of chemotherapy at Kalaignar. Despite treatment, the cancer metastasized, which enraged her family.

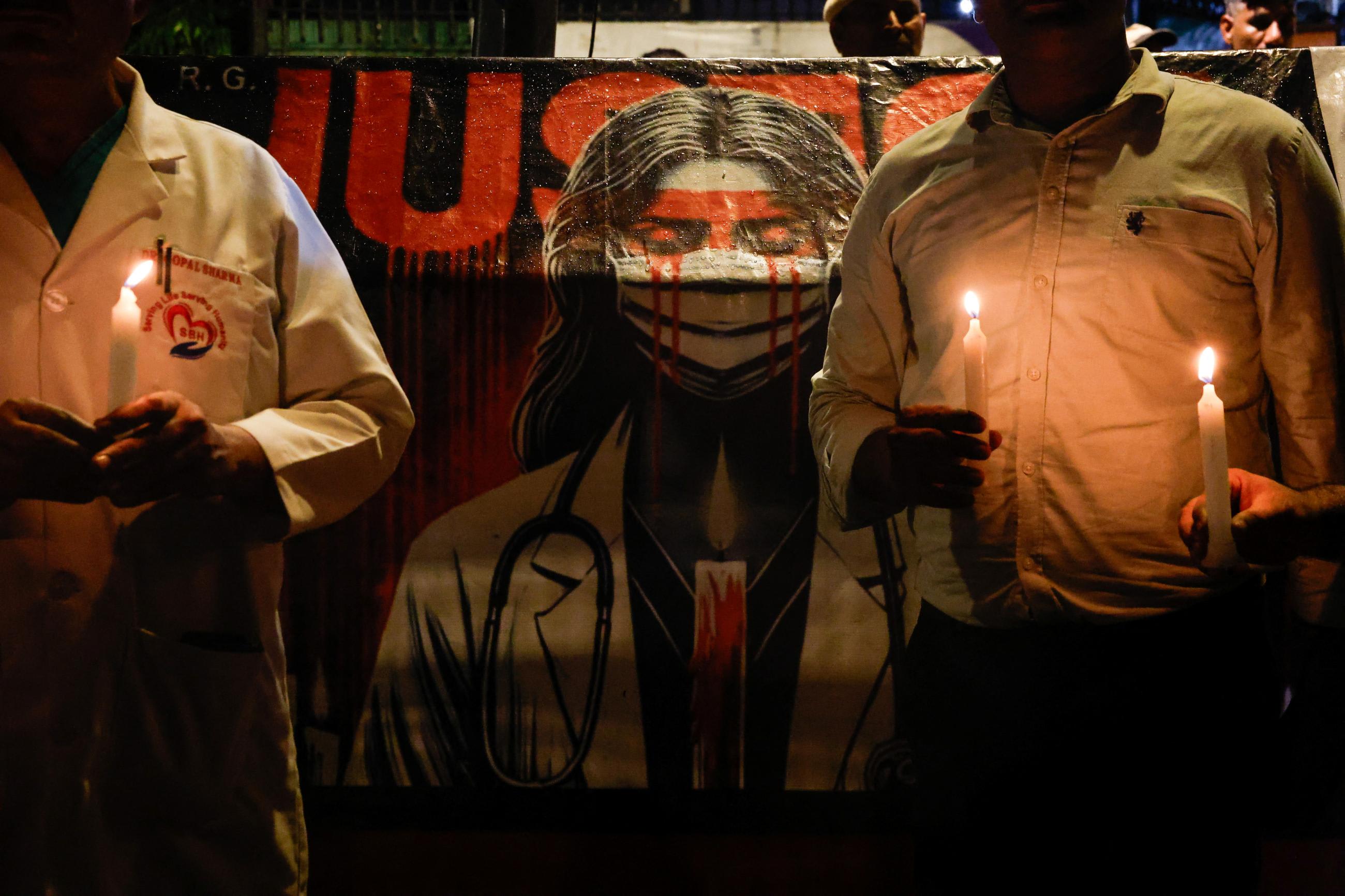

The attack on Jagannathan is a grim reflection of a growing epidemic of violence against health-care workers across India. An incident is reported almost every other week.

Many doctors and health workers believe that the media's portrayal of doctors and modern medicine plays a large role in reinforcing the existing frustrations against India's health-care system. Talking to the press from her hospital bed after her son attacked Jagannathan, the patient blamed the doctor for her condition's becoming terminal. "If the doctor hadn't failed his duty, I would not be this ill. I don't know what occurred to my son [to do this] out of his love for me. He went down the wrong road," she said.

"More than the numbers, what is alarming is the general public's reaction to these incidents," says Srujun Vadranapu, an orthopedic surgeon in Coimbatore, a city in Tamil Nadu. "I looked through the news report of this incident, and what shocked me was the number of comments by readers saying that doctors have become lazy and deserve to be beaten up. The public sentiment against doctors is predominantly negative."

In the aftermath of this incident, TheNewsMinute reported that people made violent threats against health professionals on social media, some saying they were sorry that Jagannathan had survived. The posts said he deserved to die because his treatment had failed and that other doctors should take the attack as a warning.

Shifting Portrayals

"A few decades ago, doctors were portrayed as demigods in cinema," says Mukul Kapoor, head of anesthesiology and critical care at Amrita Hospital in Faridabad. "In movies such as Anand (1971) and Amar Kahani (1949), for example, the doctors were shown to be selfless individuals who always put their patients' needs above themselves, working for little to no money and being of service."

Doctors believe that the media's portrayal of medicine plays a large role in reinforcing the existing frustrations

But the tide eventually turned, says Kapoor, and movies began villainizing doctors—a reflection of public frustration with India's health system.

"Recently, movies have begun to portray doctors as evil, money-minded, and lazy," says Kapoor. He cites the example of the movie Ramanaa (2002), which shows doctors operating on a patient who was already dead to earn money and ignoring a patient in childbirth because they were busy watching a cricket match on television.

Such portrayals are harmful, says Kapoor. "Medicine is a science and a fallible one at that. Every disease has a different prognosis and a few variables one can control. Those, too, are severely limited by the resources available at hand at the time. Only a very few bad outcomes are due to human error. So, treating doctors as demigods or villains makes no sense," he says.

In Mersal (2017), for instance, the protagonist is a well-loved doctor who treats every patient with any disease for just five rupees (about $0.06). In India, a strip of the cheapest brand of 10 500-mg Paracetamol tablets to treat fever or moderate pain costs about eight rupees (about $0.09). It's difficult to believe that even a fictional doctor would treat an illness for this price.

However unreasonable this might sound to health-care workers or policymakers, says Kapoor, this is what the Indian general public expects. They want private health care to be free or nominally priced. They don't want to go to public hospitals, which are free (or nominally priced), because of infrastructure issues, overcrowding, and worries about care being of bad quality.

"Their expectations of quality health care at nominal prices are very reasonable," says Mohammad Aslam Ali, a dermatologist in Guwahati. "However, these issues are systemic, and the public demand and pressure must be on government authorities and elected representatives."

Ali says patients and their families who decide to vent their anger and frustration at health-care providers are short sighted:

"Indian media are knowingly or unknowingly peddling this shortsightedness. If a patient feels ripped off by a private hospital, [they believe] it's the doctor's fault for being well paid rather than the corporate greed of the hospital administrators."

"Similarly, when a patient receives low-quality care at a public hospital, people believe it is because the doctor is lazy rather than because the hospital is inadequately staffed or has severe resource limitations. They do not consider that elected representatives have not invested in the system."

Improving Health Literacy

Jayadatt Pawar, an upper gastrointestinal tract surgeon from Bangalore, says that unbalanced reporting in news media is a significant contributor to the growing distrust between the public and health-care workers.

"Indian journalists often focus exclusively on the patient's perspective, leaving the doctor's side of the story unheard," he says. This one-sided approach, he argues, not only misrepresents medical realities but also exacerbates public anger toward doctors.

Pawar says health reporting in India frequently lacks scientific rigor and factual grounding. "There is no explanation in the news about the patient's medical condition, the available treatment options, or the realistic outcomes. Such details would help ground the narrative in facts, not emotions, but they are often ignored."

He stresses the importance of having science-literate journalists cover health-related stories. "Science-related stories should be communicated by journalists who understand the subject. This ensures the nuances are captured accurately, leading to informed and balanced reporting."

Gayatri Sharma, an emergency physician and medical illustrator based in Mumbai, says major information differences between health-care providers and patients in India complicates the problem. "This information asymmetry exists partly because the Indian health-care system is not transparent and partly because of poor health literacy in the general population."

The primary way to break this cycle of violence is by investing in improving health-care infrastructure in public health systems

Vadranapu notes that when he was in France on a fellowship, he worked with an orthopedic surgeon specializing in upper-limb problems. "I was amazed at the way the patients were able to understand and communicate with the physician. They could hear about their options calmly and collaboratively make decisions with the treating doctor because they had good health literacy. This has not been my experience in India."

"A poor ability to comprehend health information is not the function of a lack of education per se, but instead a lack of basic health-related education," says Pawar, adding that he has treated highly educated patients who could not grasp their treatment options and their implications.

Pawar says that health literacy should be a part of everyone's education beginning in high school. "A few hours dedicated to teaching people accurate information not only about how their bodies work but also about how medical systems work and how evidence-based medicine is practiced is crucial to ensure that people understand the medical information communicated to them via media and their health-care providers."

Complementing this, regular community outreach programs and public awareness campaigns can help demystify the limitations and complexities of modern medicine, fostering trust between patients and health-care providers, says Sharma.

A study published in 2013 shows that a community-based educational intervention in south India for pregnant women with anemia was successful in improving their understanding of the condition and empowered them to make better health decisions, such as choosing iron-rich foods and supplementing their diets with iron therapy.

Pawar says the media's lack of factual grounding and widespread health illiteracy creates a dangerous cycle of misinformation and misplaced blame.

He cites a clip of an Indian television series that went viral of a man dying during surgery. When the surgeon breaks the news to the family, the wife, who isn't a health worker, says the doctor can't be right and asks to go into the operating room. She dons scrubs and operates on her husband, saving his life with the power of her love. "These are the tropes being peddled to the Indian population," Pawar says.

Health literacy should be a part of everyone's education beginning in high school

Pawar remarks unrealistic portrayals of disease conditions and miracle cures that permeate the Indian fictional entertainment world interplay with poor health literacy and media literacy to create barriers that prevent the population from fully understanding the complexities of modern medicine.

"These very same movies and television series in India offer people a resolution to their frustrations by portraying violence against the villains [doctors or health professionals] as a feasible answer in these scenarios. This, too, promotes the use of immediate violence to avenge perceived slights," says Karun Saathveeg, a third-year medical resident at Gangaram Hospital in Delhi.

"The primary way to break this cycle of violence is by investing in improving health-care infrastructure in public health systems and standardizing rates across the private hospitals and making them transparent to the patients," says Sharma.

Health workers across India have been protesting and demanding a central law to address violence against health-care workers. On top of this, Pawar says, is a real need to demand media accountability and responsibility to help bridge the gap of mistrust between the health system and the public.

Pawar says developing and adhering to ethical guidelines for health-related coverage can promote balanced, factual narratives, counter sensationalism, and prevent undue vilification of health-care professionals.

He says it's also necessary to advocate for responsible storytelling in film and television. This can be achieved when filmmakers and content creators collaborate with health professionals to create accurate portrayals of modern medicine and its challenges.

"Media has burned the bridge between the general population and health-care workers, but it has the power and the responsibility to rebuild it," says Pawar.