The paradox of urban health is that investments in disease surveillance, clean water and sanitation, and improved housing were often spurred by plagues, but ultimately made city life healthier. COVID-19 offers a similar opportunity: to advance reforms that improve health in the long-run. In so doing, it would reverse decades of underinvestment in urban health in low- and middle-income countries.

In the nineteenth century, tuberculosis and water-borne infections persistently ravaged city life in American and European cities and led to the creation of the first effective metropolitan public health agencies, staffed by medical professionals rather than aldermen. Public terror over cholera, yellow fever, and typhoid overcame taxpayer objections to municipal investments in piped clean water and sanitation. New public health boards pushed for housing laws, forced property owners to connect to new waterworks, and built sewers at a breathtaking pace.

The share of urban U.S. households supplied with filtered water grew from 0.3 percent in 1880 to 93 percent in 1940

In 1857, no U.S. city had a sanitary sewer system; by 1900, 80 percent of Americans living in cities were served by one. The share of urban U.S. households supplied with filtered water grew from 0.3 percent in 1880 to 93 percent in 1940. These and other improvements in water accounted for nearly half of the decline in mortality in U.S. cities between 1900 and 1936. Through this combination of public health reforms, laws against overcrowding, and better sanitation, European and North American cities transformed from "the most helpless and devastated victims of disease," to quote Jane Jacobs, into "great disease conquerors."

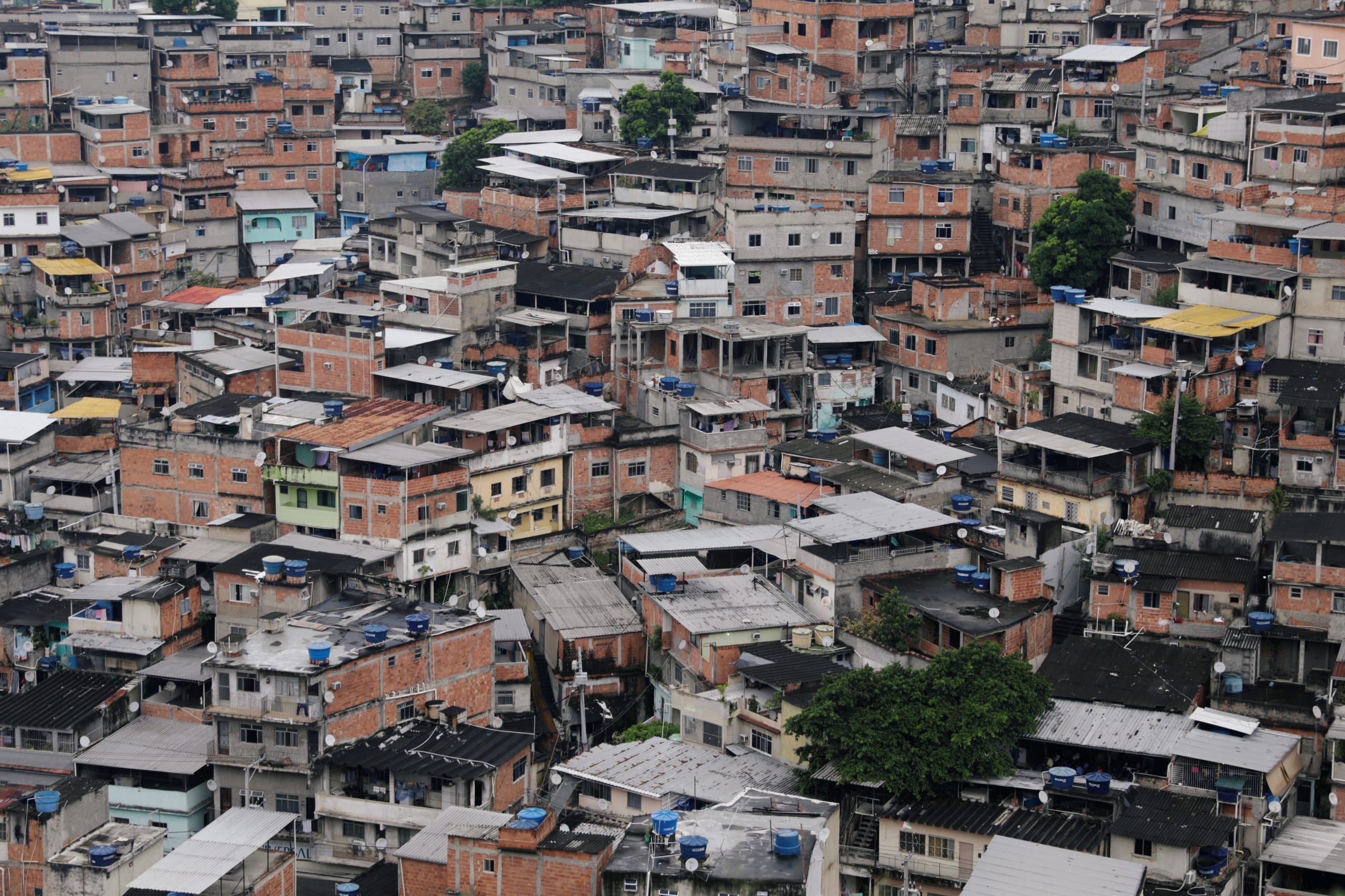

The novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, has not been a plague of cities per se. First identified in Wuhan, a Chinese transportation hub city of eleven million people, the pathogen traveled quickly to major cities around the world, but it has not depended on urban density for subsequent transmission. A year into this pandemic, population density is not linked to higher reported coronavirus cases or deaths. Economic geography, rather than cityscapes or urban density, has determined contagion risk in this pandemic. The hardest hit areas have been those defined by overcrowding, poor and socially marginalized residents, dependence on the informal economy, and inadequate access to public services. Many of the areas ravaged most by this pandemic, such as South California and São Paulo, are characterized by sprawl rather than tightly packed streets.

Higher Population Density Is Not Correlated With More Deaths

Population density has not been a good predictor of COVID-19 mortality

Yet, while COVID-19 is not a disease of density, it is an urban health crisis. Most of the world's population resides in cities and towns, and hence, that is where most of COVID-19 cases are reported. The economic geography that has enabled rapid spread of this virus is not exclusive to cities, but it is present in many of their neighborhoods. And it accounts for the high reported case counts, economic devastation, and social turmoil in poor or marginalized areas, from Hong Kong's Kowloon district to Dhaka's shantytowns to the favelas of Rio de Janerio. In Mumbai, India, seroprevalence testing found that 54.1 percent of slum residents had been infected by COVID-19, compared to just 16.1 percent of those in other areas. These differences were measurable when even less than 100 meters separated neighborhoods in Mumbai.

In slums, where many individuals cohabit in the same homes and buildings are close together, keeping one's distance is all but impossible, and inconsistent public services further aggravate conditions. For example, Cañada Real in Madrid, the largest informal settlement in a European city, has been without electricity since the beginning of October, forcing families to congregate for warmth in already cramped quarters and to leave home for income or education. For millions of urban poor, access to water and electricity—tools necessary for sanitation, heating, and remote work or school—is not guaranteed. Slums in New Delhi, Chennai, Nairobi, and other major cities in low- and middle-income countries have faced water shortages throughout the pandemic, impairing or preventing basic mitigating measures like handwashing.

In Mumbai, India, seroprevalence testing found that 54.1 percent of slum residents had been infected by COVID-19

When the urban poor do fall ill, local health services may be insufficient to provide lifesaving care. In Brazil's favelas, for example, residents almost exclusively depend on public hospitals and clinics, where COVID-19 fatality rates are nearly double those of private hospitals. To date, more residents of Rio de Janeiro's favelas have died from COVID-19 than in all of Nigeria and South Korea—countries with a combined population roughly 168 times greater than Rio's favelas . Similarly, the health-care systems serving urban slums and informal settlements often lack basic resources, including physical space, to treat ill patients; Dhaka, Bangladesh, for instance, has just 80 public ICUs, despite having a population of almost nine million people, 40 percent of whom live slums.

These urban health systems may also fail to prevent further spread in the community. Without robust testing, identifying positive cases remains a challenge, and even where testing is accessible, local health systems often lack the additional resources to contact, monitor, and enforce quarantine of exposed individuals. Some slum residents are even forgoing preventative care, citing their fears of COVID-19 infection, declines in income, and restrictions on movement.

Will COVID-19 spur the municipal investments and societal reforms needed to address deficiencies revealed by this pandemic? Perhaps, but it will require reversing decades of underinvestment in urban health in low- and middle-income nations.

Over the past 50 years, the traditional process of urbanization—of public health development before economic and population growth—has reversed, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Through medical interventions funded by higher-income nations, international organizations, and aid groups, the average lifespan in poorer countries has increased dramatically. As deaths from infectious and other preventable diseases have declined, more people are moving to cities, and more city-dwellers are surviving into adulthood. These increases in longevity are rightly celebrated. But rapidly expanding cities have not invested in the infrastructure and shoe-leather public health measures necessary to sustain healthy urban populations. Instead, they have become dependent on foreign interventions and aid.

Many nations are seemingly resigned to losing control of the pandemic and are pinning their hopes on a vaccine, and the prospects for urban health reform seem uncertain. But, for most cities, waiting for a vaccine is not a sound or ethical response. Most low- and middle-income nations are not expected to achieve widespread vaccination until 2022 or even 2023. Moreover, a vaccine against the novel coronavirus will not protect cities or the urban poor from future pathogens or routine infections. To combat COVID-19 and emerge from this crisis safer and more resilient, cities should return to the basics.

Most low- and middle-income nations are not expected to achieve widespread vaccination until 2022 or even 2023

First, governments should ensure communities have access to non-discriminatory public health services and products. In the immediate future, this will require scaling up contact-tracing services, on-the-ground disease surveillance (such as screening households for fever or low oxygen levels), institutional quarantine, and access to clean, low-cost water. Health services, including preventative care and waste management services, should be deemed essential, and COVID-19 mitigating care and vaccinations should be provided at low- or no cost. Once cities emerge from this pandemic, these efforts should shift to long-term investments in basic urban infrastructure, including affordable electrification, waste management, and sanitation systems.

Second, cities should look to support the urban poor through social protection schemes and comprehensive labor and housing regulation. Cash transfers, unemployment insurance, and universal health coverage are powerful tools to protect the most vulnerable from the economic and social effects of this and future health crises. But cities should also look to institutionalize protections for their most vulnerable, such as through housing or labor regulations. For their part, the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and other financial institutions should provide financing to help nations and cities realize these goals.

Although COVID-19 may be the greatest public health crisis in a century, it is certainly not the last. The conditions that have rendered informal settlements and urban slums so vulnerable to this pathogen and its secondary effects will persist unless cities are willing to invest in the tried and tested public health measures and societal improvements that once defined urban progress. Failure to do so will fall disproportionally upon the urban poor.