White supremacy is global. The American expression of it is exceptional, but it is by no means singular. Like many Americans, I’ve been grappling with the ugly and brutal manifestations of racism. I’ve also been reflecting on my role in perpetuating racism and how I have benefited from white supremacy and the struggles of Black Americans.

Like many Americans, I’ve been grappling with the ugly and brutal manifestations of racism

Like many Asians, my family immigrated to the United States in the early 1970s, and were beneficiaries of the loosening of immigration rules made possible by the civil rights movement. We played into the hands of the white establishment by allowing ourselves to be considered “model minorities,” a category established to pit us against Black Americans. This wasn’t hard since we came from communities that were also racist and have their own caste-based traditions of discrimination. More and more I am realizing that my “success” has little to do with my actual achievements and much more to do with a system that rewards non-Blackness. And I have no doubt that I would be even more “successful” if I were a man.

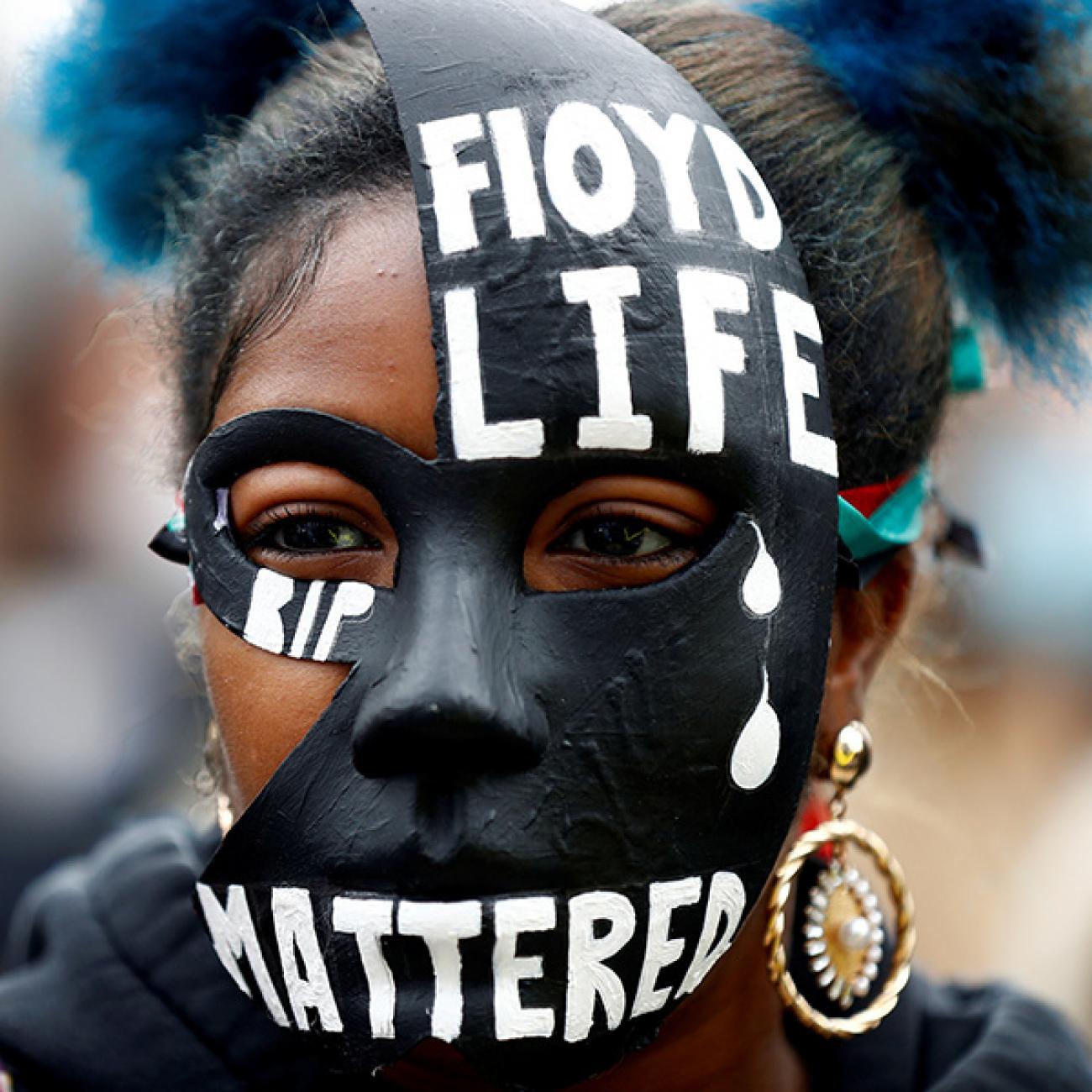

The global reaction to the murder of George Floyd and the revelations of systemic racism that Black Americans experience should not be a surprise. Every country has been touched by white supremacy through colonialism and its allied systems of slavery and apartheid.

We are complicit agents actively engaged in upholding a worldview that denies the humanity of certain groups

Such systems could only thrive if non-whites were categorized as different or less than white and Africans were dehumanized, making it easy to buy and sell them as commodities. But the true insidiousness of white supremacy is that other non-white and non-Black groups support the centering of whiteness just so we can get close to that center. Around the world, being white (or fair in South Asia) is more beautiful, English is the language of power, and we seek to emulate all things white. The unconscious hope is that we will finally be included in the secret, powerful club of whiteness if only we can master the tools of the dominant culture—we go to the right schools, get the right degrees, dress the part, and most disturbingly, we don’t look back as we make our way up. We aren’t just passive observers; we are complicit agents actively engaged in upholding a worldview that denies the humanity of certain groups.

Centering Whiteness, Globally

In the global health and human rights community, where I sit professionally, there’s been a lot of discussion in the last few years about decolonizing global health. What we don’t talk about explicitly enough, however, is how white supremacy operates in this sector. In many cases, we focus on diversity, equity and inclusion, mentorship, and funding strategies—which are all important. What we don’t talk about is how the structures and operations of our organizations are part of white supremacist culture. We don’t talk about how white people and those who center whiteness, including me, support policies and programs that perpetuate neo-colonialism. I say this even as a woman of color leading an organization with staff who speak multiple languages and come from different backgrounds. White supremacist culture is so powerful, and we are rewarded in so many ways for conforming to it, that we are sometimes blind to its influence.

White supremacist culture is so powerful, and we are rewarded in so many ways for conforming to it, that we are sometimes blind to its influence

Why does global health, or “tropical medicine” as it was called in its early days, even exist? Tropical medicine was an effort to ensure that white people wouldn’t die in malarial and yellow fever-ridden zones so that the governing (white) colonial power's interests and resources, including other humans, could be exploited. Even now, places that receive international aid are prioritized to receive funding based on their relevant importance to groups of donors, which are largely white-led governments and foundations. Are we still serving neo-colonial masters? Why do we in the global health sector, which is dominated by white people, especially white women, believe that we know how to solve the health problems of people in other countries? In what ways do we trivialize local knowledge because it doesn’t adhere to white notions of expertise and denies us the chance to be saviors? Is that delusion, arrogance, or both? In caring, are we condescending?

What makes us think we can treat poor people in distant lands as “beneficiaries” of our money, or “targets” of our interventions? What makes their lives a “deliverable” or outcome? Is that not just another form of objectification? Do our degrees, money, and our good intentions give us the right to do this? Do we not make money on Black bodies as well? As development assistance for health has increased substantially over the last two decades, billions of dollars are “awarded” to international NGOs to improve health outcomes in Africa.

An Imperfect March Toward Justice

The linkages between colonialism and patriarchy, between racial justice and gender justice are undeniable. They have—and still do—oppress Black and brown women. My life’s work—making sure that women survive and thrive—is a radical act and though I’ve been involved in social change since I was a teenager, now I am consumed with more questions than ever and have few answers, if any.

In this moment of American history, I am struggling to come to grips with the actions that I’ve taken over my lifetime that have centered whiteness, denied the value or worth of Black people whether in the United States or overseas, and how that has undermined my own growth as a person. It is not enough to be merely “not a racist.” We must all understand what anti-racism truly means in all aspects of our lives. While I’m not sure what this means for global health, I do know that good intentions are not enough. I also know that the global health infrastructure needs a radical overhaul and that it will take time to dismantle it. Tackling problems like injustice, inequality, health disparities, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and today’s coronavirus pandemic requires brutal honesty about our problems and the lack of solutions. The system is far from perfect; our responsibility is to reimagine it, so that we can realize the promise of a better world for everyone.

Justice is an ever-changing aspiration

Here’s my pledge: I will not be paralyzed by my questions or my lack of complete understanding. I know I am part of a system of oppression and so is the institution that I lead, even as we work to dismantle oppression. We must hold these contradictory thoughts simultaneously and live with that dissonance. I also know that we can be part of the solution if we recognize the truth in the lived experience of those who are being oppressed. Justice is an ever-changing aspiration and one that we will never achieve perfectly, but we must continue our imperfect march toward it.