On October 26, 2022, the heads of the intelligence services of Russia and other countries who were once part of the Soviet Union gathered in Moscow. They agreed to act against foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that, as they put it, use "soft power" to "destabilize" their countries, according to Russian news agency TASS. One of those governments, Kyrgyzstan, promptly published a draft bill to give authorities more control over the activities of NGOs. Under the planned legislation, all NGOs in the country must re-register by the end of 2023 or face closure. Human rights activists fear that this will allow the authorities to eliminate all undesired groups and are campaigning to stop the bill from becoming law. But if it passes, civic groups may soon have to operate under conditions similar to those in neighboring Uzbekistan, where a decree issued in June 2022 further raised some already high hurdles for NGOs, by granting government officials discretionary power to deny approval for NGO projects receiving foreign funding and giving "state partners" oversight of approved projects.

Cases such as Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan are not exceptional. By one count, the number of governments that had laws restricting NGOs increased from twenty-two in 1992 to sixty-six in 2016 (out of a sample of ninety-two countries). Such laws seem to have achieved their main purpose; some countries' laws hampered the work of groups perceived as critical of the government and diminished their ability to bring abuses committed by officials to the attention of domestic and international audiences. Our research in the British Journal of Political Science shows that the laws also had an effect that their creators probably did not intend: they seriously damaged the health of their populations and cost thousands of lives.

Some governments routinely harass NGOs with violence against staff and activists, but passing laws against NGOs is also a tool to counter activism

Collateral Damage

While many governments routinely harass critical NGOs through violence against staff and activists, passing laws against NGOs can also be a useful tool to counter their activism. By using the legal system, governments can discourage criticism, ensure that their measures against activists are not thwarted by the judiciary, make repression more acceptable in the public eye, and can help mitigate international reproach. But formal laws have a drawback when used as a tool to stifle criticism: they usually need to be written in general terms and typically apply to almost all nonprofit organizations—including health NGOs—even though most of them are not perceived as threatening by the authorities. As a result, NGO laws often affect "bystander" NGOs that are not concerned with politically sensitive issues. They too become subject to complex, time-consuming, and expensive registration. These NGOs must pay the costs of regular reporting and face constraints on how they can receive and use their resources. For instance, in 2022 the Indian government withdrew the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) licences of thousands of entities, including the Indian Medical Association and the Tuberculosis Association of India, hampering their international collaborations.

NGO laws often create significant uncertainty. Nonprofit organizations may not know what is expected of them and may worry about coming under the unwelcome scrutiny of officials. This burden and uncertainty adversely affect even activities that governments are happy with, including health care. Restrictive NGO laws can lead to health NGOs using their resources inefficiently, disbanding, or they may thwart new health NGOs from being created.

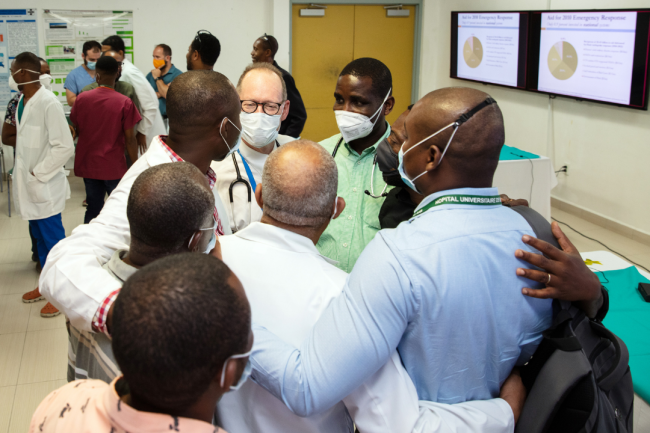

When NGOs link up across borders, it is usually good for health. International NGOs (those with members in multiple countries) spread medical knowledge and best practices among health professionals—as is the case with the International Council on Women's Health Issues, for example. Groups such as the International Confederation of Midwives help policymakers find and implement better health policies and ensure that the interests of stigmatized communities, women, and children are considered. International NGOs such as Doctors Without Borders and Caritas Internationalis also improve people's health by funding and running community health services. Governments do not usually think of these and other health-sector NGOs when they introduce restrictive laws on international NGOs—unless they are aiming to restrict reproductive and LGBTQ+ health organizations. Nevertheless, health NGOs suffer from the higher administrative hurdles, constraints, and uncertainty imposed on the non-governmental sector as a whole.

Sometimes, health NGOs are hampered through active government intervention, as in the case of Russian authorities classifying certain public health organizations as "foreign agents" (against the wishes of the organizations). More often, they are indirectly affected, for instance, by rules that delay government approvals. Opponents of restrictive laws also warn of the risks to peoples' health. For example, when Kenya's parliament debated a proposal for such a law in 2013, one of its members pleaded with government officials, noting that NGOs "are providing 47 percent of the health services in Kenya today… does the government want us to die after the NGOs are removed from the country?"

The Health Burden of Illiberalism

To provide systematic evidence of the link between laws restricting the international connections of NGOs and peoples' health, we conducted a statistical analysis of ninety-five countries from the early 1990s through 2017. We documented two worrying effects of NGO laws. First, as we suspected, countries saw less presence of international health NGOs within their borders after their governments introduced a restrictive law. This finding suggests that restrictions severed existing links among health workers, discouraged the creation of new ones, or both. Second, restrictive laws were associated with worse health outcomes for people.

Overall, people are healthier than they were thirty years ago due to better health care, sanitation, and other factors. However, in countries with restrictive legislation, these improvements have been hampered. We estimate that, all else being equal, countries that restricted the international work of NGOs missed out on nearly forty percent of the yearly progress in improving standard health indicators that we observed globally between 1993 and 2017.

A complex set of factors influences human mortality rates, and figuring out what mortality would have been if one factor had been different is fraught with difficulties. However, based on statistical models and some assumptions, we estimate that the global excess mortality due to restrictive NGO legislation amounts to hundreds of thousands of deaths every year. These estimates can help us gain a fuller picture of the human cost of contemporary illiberal politics around the world.