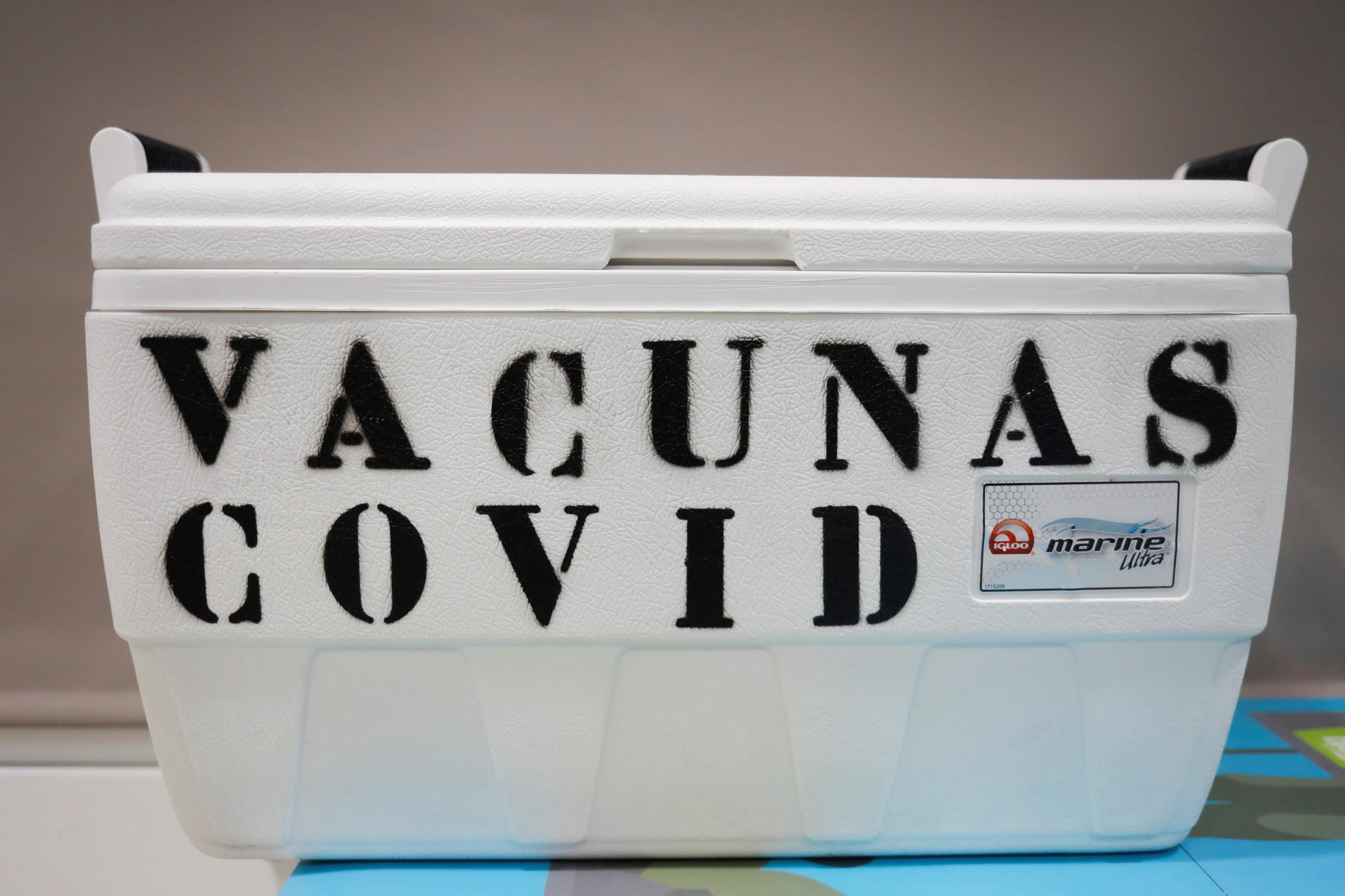

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, many African countries struggled to get shots into arms; one of the biggest reasons they did was that they couldn't store and transport vaccines at the appropriate temperatures. Cameroon, in Central Africa, had one refrigerated truck that could safely transport vaccines. Mali, in West Africa, had two.

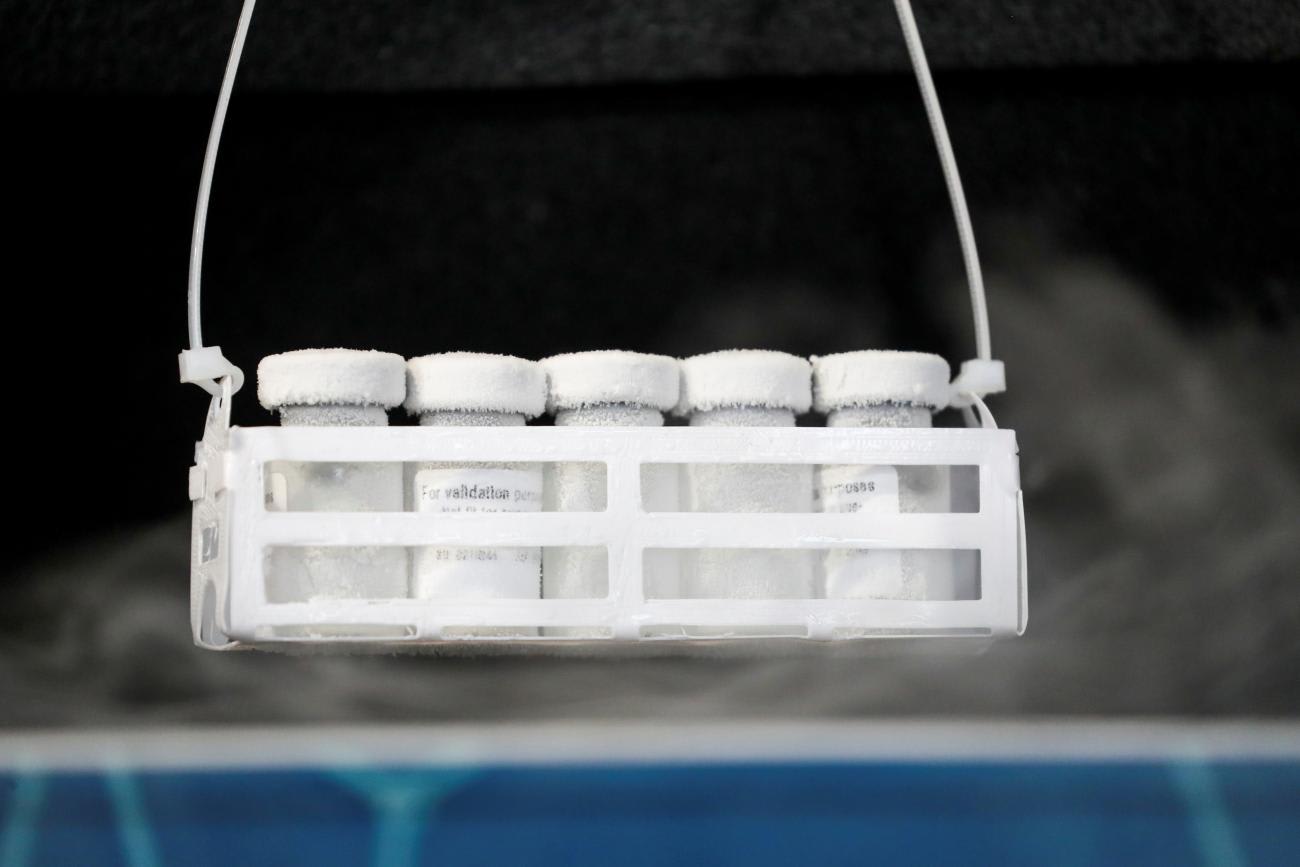

Many of the COVID-19 doses Africa received needed to be maintained by ultra-cold-chain technologies at temperatures colder than -70°C (relative to most other vaccines, which can be stored and transported between 2°C and 8°C). Few developing countries had the necessary ultra-cold-chain equipment at the start of the pandemic. Samantha Power, administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development, recently drew attention to this, saying, "Last-mile challenges like cold chain storage, power outages, are causing millions of vaccines to be wasted and thrown away."

The situation has improved. In 2021 alone, UNICEF delivered eight hundred ultra-cold-chain freezers to nearly seventy countries, with a storage capacity of two hundred million mRNA vaccines. Donor countries have also contributed. As of January 2023, Japan alone had donated nearly $140 million (¥18.5 billion) to seventy-eight countries and regions to extend the cold chain through its "Last One Mile Support" program. A new partnership between the Mastercard Foundation and the Africa CDC, Saving Lives and Livelihoods, is helping deploy vaccines, dedicating substantial resources to strengthening cold chain in countries where it has proved to be a significant barrier.

But gaps remain, particularly in countries' capacity to scale up ultra-cold-chain technologies. Many need to strengthen infrastructure that allows for more consistent and stable electric supply so that cold chain equipment remains stable and does not fail. In the event of a power failure, a backup power supply helps ensure that temperature-sensitive health commodities can continue to be stored at the appropriate temperatures. Cold chain handlers in Africa point out that outages there can be quite long.

Three children died after being administered measles-rubella vaccines that a nurse had taken from a primary health center's cold storage

Further, the process for delivering vaccines within countries is complex and multiple actors operate in silos, especially in developing countries. On their way to the final recipients, vaccines often traverse varying climates and topographies and are almost certainly handled by numerous organizations, both public and private, that have varying levels of motivation, knowledge, and financial and human resources.

According to a study by a group of leading Indian public health experts on immunization practices among private medical practitioners of Bhopal city in India, a majority of the private-sector pediatricians surveyed were using, out of ignorance, inadequate domestic refrigerators to store vaccines. Such actions can be fatal. In the Indian state of Karnataka, three children died in January 2022 after being administered measles-rubella vaccines that a nurse had taken from a primary health center's cold storage and kept in a hotel refrigerator.

Vaccines are not the only health commodities that require an end-to-end cold chain. Blood and its components — insulin, biological samples, and some medicines as well — need to be stored and transported within precise temperatures; unfortunately, not enough attention has been given to the cold chains for them. During a February 2023 webinar titled "How reliable cold chain infrastructure can ensure blood management in India," blood management experts from leading institutions across India, which included blood banks, hospitals, and research institutions, lamented the scarcity of people who understand the importance of storing and transporting blood at the right temperature, even among those who do so professionally.

Some blood banks are limited by financial resources. At a prominent one in Bengaluru, India, a senior staff member who was not authorized to speak on the record said that the organization did not have funds to upgrade their cold chain equipment, much of which was more than a decade old. Supporting immediate care for those who need blood almost always trumps buying new cold chain equipment.

The good news is that recent advances in cold chain technology are helping alleviate some of these challenges, particularly when it comes to last-mile delivery. Some technologies allow managers to monitor cold chains and correct problems in real time. Solar Direct Drive refrigerators and freezers, which are powered directly by sunlight, without the use of batteries, are an environmentally friendly option for areas without reliable electricity. Companies are developing lighter boxes to carry temperature-sensitive health products to remote and hard-to-access areas via drones. India is deploying these innovations on a substantial scale in the remote northeastern corners of the country, where long power outages and the difficult terrain leave few alternatives.

Although the right solution for any given cold chain and product will vary, it is clear that these technologies can help in the fight against pandemics and legacy diseases. No one should be denied essential health services because of a health system's lack of capacity to safely store and transport vital medical products.

Nearly half of all vaccines are discarded every year, and failure to maintain an unbroken cold chain is among the top causes

Still, organizations across the private and public sectors can do more.

First, the research community should present compelling evidence to support increased investments in vaccine and medical cold chains. Estimates from the World Health Organization suggest that nearly half of all vaccines are discarded every year; failure to maintain an unbroken cold chain is among the top reasons for it.

Second, governments and donors should invest not only in new infrastructure but also in maintaining and upgrading existing cold chain equipment. Donors finance fixed expenditure such as refrigerators or vehicles for vaccine delivery but they do not adequately finance recurrent costs for operating cold chain equipment, according to a report by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

Third, governments should create a regulatory environment that encourages adopting better cold chain practices. The Drug Controller General of India issued guidelines in 2022 that require all blood cold chain devices to be medical grade. The World Health Organization provides recommendations on safe transportation and storage of commodities such as vaccines, blood, and pharmaceuticals. These are a good starting point for other regulators.

Fourth, civil society and international organizations should build awareness about the importance of cold chains, disseminate best practices for managing them, and train people to adopt them. Cold chain technology has evolved significantly over the years and new technologies are being tested every day — yet capacity-building lags. Senior government officials who influence procurement decisions must also be well informed.

Fifth, the private sector needs to develop more environmentally friendly, cost-effective, and easier-to-use cold chain technologies. Green refrigerants and solar-powered cold chain reduce the direct and indirect environmental damage caused by cold chain equipment, but costs can be an obstacle. In Latin America, national immunization programs have found it challenging to maintain and upgrade cold chain equipment. More cost-effective technologies might alleviate this situation.

Finally, all these stakeholders need to work together to find locally relevant options. The challenge is not unresolvable, but it cannot be addressed by any one actor alone.