During and for two hours immediately following the presidential debate between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump in September, abortion was the most searched topic online, according to an analysis by New York University researchers.

Not surprisingly, immigration came in second.

As Heidi E. Jones, a reproductive epidemiologist, and her co-authors noted in a recent Journal of Migration and Health article titled "Abortion Care Access and Experience Among U.S. Immigrants: A Systematic Review," "The geopolitical intersection between immigration and abortion policy makes this a particularly salient issue." With the election only weeks away, Think Global Health reached out to Jones to discuss the findings of her study and strategies she believes can help ensure greater abortion access among immigrant populations.

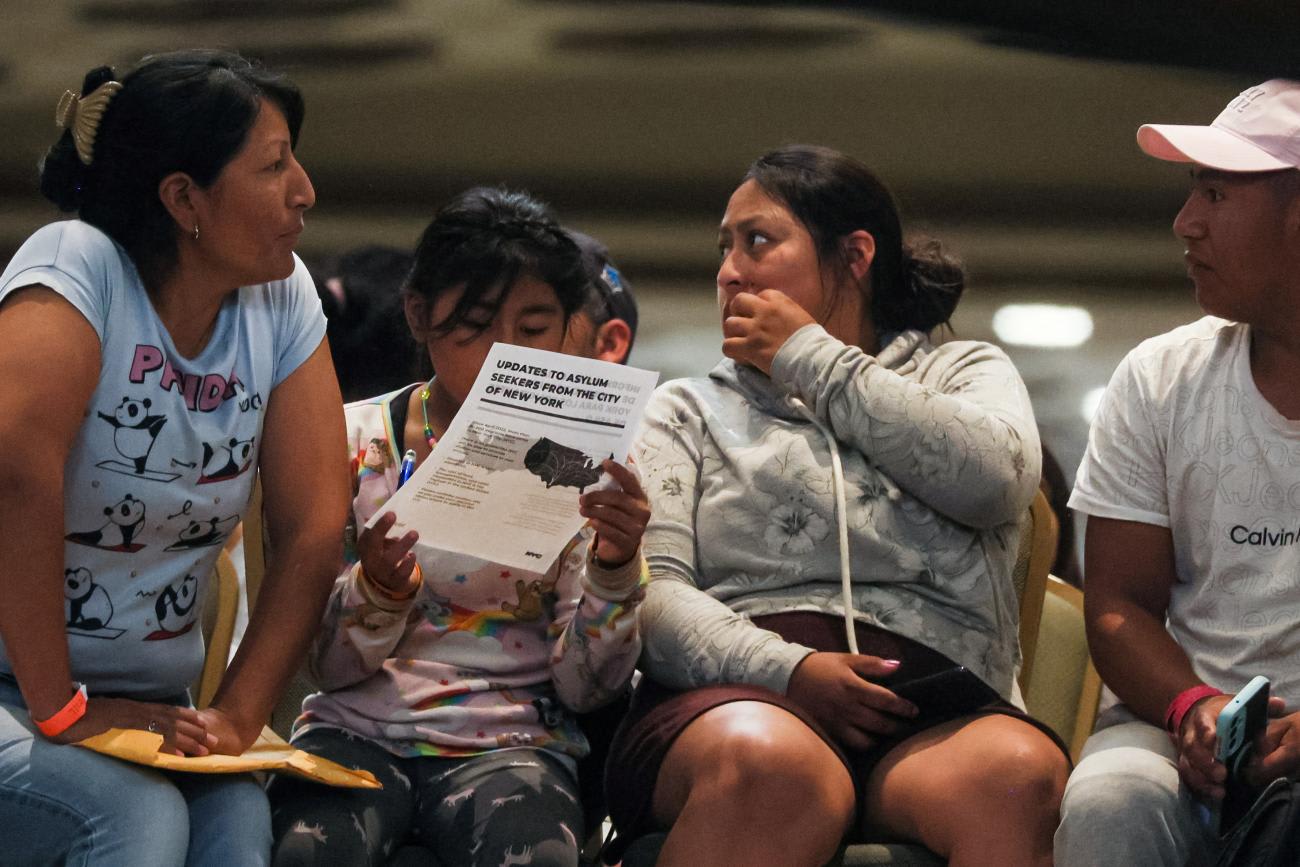

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, abortion remains legal in New York for any reason up to 24 weeks of pregnancy or later if a pregnant person's health is at risk or their pregnancy will not survive. Among those seeking medication abortion at the New York City Sexual Health Clinics so far this year, 47% reported being born outside the United States and Puerto Rico. Neither the city's clinics nor the New York City Abortion Access Hub, a confidential, bilingual hotline, ask people seeking services about their immigration status.

Jones, who grew up and works in New York City, said that as a teenager she was passionate about sexual and reproductive health, an interest that intensified with the onset of the HIV epidemic in the 1980s. Currently a professor at the City University of New York (CUNY), she has spent her career studying ways to improve reproductive health outcomes—both in the United States and globally—while maintaining individuals' autonomy over their care decisions.

She has lived in Burkina Faso and Senegal and serves on the editorial board of Contraception, an international reproductive health journal. Jones received her doctorate in epidemiology from Columbia University and master of public health from Hunter College.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: You're an epidemiologist by training. What led you to study sexual and reproductive health?

Jones: Sexual and reproductive health are often siloed or othered, largely on the basis of cultural taboos and hang-ups as well as sexism and the desire to control women's sexuality. Ignoring sexual and reproductive health leads to poor health overall, especially for women, but also for men and all genders.

Think Global Health: Why hasn't more research been done in this area?

Ignoring sexual and reproductive health leads to poor health overall, especially for women, but also for men and all genders

Jones: Many pregnant people are having a hard time accessing abortion services in the United States right now, so it is hard to know where and what to focus on.

As someone who has been doing research on abortion for the last 25-plus years, it is demoralizing to see how so much of the data is ignored by many policymakers. Clearly it is important to continue to do abortion research, but it is frustrating when policies are passed based on political ideology that contradict scientific evidence.

Think Global Health: Based on your research assessing immigrant access to abortion, do you think this issue is getting adequate attention?

Jones: It is hard, in general, to access abortion in the United States right now, with so many states banning or limiting access for all pregnant people. Immigrant groups likely experience these limits differently, given the compounding nature of intersectional identities.

Migrant farm workers often work in remote areas with limited access to health services. Undocumented workers may avoid going to the clinic altogether because of fears about their legal status. Clinics and providers may not be trained to provide culturally competent care, which can lead to negative experiences even among documented immigrants. Experiences with sexual violence or other forms of intimate partner violence, for example, among refugees and those displaced by war, can also affect access to and use of sexual and reproductive health services, including abortion services.

Think Global Health: Your Journal of Migration and Health article identified three obstacles to immigrants seeking abortion services. What are they and how can they be addressed?

Jones: In our systematic review of abortion access among U.S. immigrant populations, we found three papers that compared barriers to abortion between groups. Each paper identified a different barrier.

The first was experiences with mistreatment in health care and the legal system. Strategies to address this barrier include universal access to health-care services (regardless of documented visa status), ensuring access to translation services, and training people in culturally competent care.

The second was challenges in navigating the system, such as finding ways to set up appointments. Increased outreach in multiple languages and strengthening referral systems from social services and other community-based organizations working with immigrant populations are two ways to facilitate increased ease in making appointments.

The third was a general lack of knowledge about legal rights. Again, ensuring that outreach and educational materials on abortion services are available in multiple languages and working with community-based organizations can help to solve this. In general, the legal status of abortion is changing in many states and misinformation can spread easily.

The impact of culture on access to sexual and reproductive health is a global phenomenon

Think Global Health: Are any organizations currently working to support these types of solutions?

Jones: Many local abortion access funds work in and with communities to ensure abortion access. The New York Abortion Access Fund is one example, and similar funds exist in many states. Several national organizations work across migration status for subpopulations, such as the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice and the National Asian Pacific American Women's Forum.

Think Global Health: Shifting to New York City, can you speak to the environment here?

Jones: My sense is that access to abortion services in New York City remains quite good. We have both a mayor and governor who support reproductive choice, and now also both a strong system in place to identify abortion providers through the New York City Abortion Access Hub as well as increased availability to medication abortion via telemedicine. It will be important to evaluate how well these services are reaching people.

Think Global Health: What role do cultural attitudes play in whether people can access reproductive health care and, perhaps more important, exercise individual autonomy to make the choices that are best for them?

Jones: Cultural norms around gender roles, sexuality, family formation, marriage, gendered access to education, and employment all affect access to sexual and reproductive health care and reproductive autonomy. Researchers see this very clearly today in the United States, with a lot of discussion recently on social media around what it means to be a "childless cat woman."

That this discussion is happening while so many states have blocked or reduced women's access to abortion is a sign of the cultural values in some subpopulations, although the data suggests that the majority support reproductive choice.

The impact of culture on access to sexual and reproductive health is a global phenomenon.