Despite the rapid upward trend of aesthetic procedures globally, essential reconstructive surgical needs for conditions including cleft lip and palate are not being met in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

According to a recent global survey on aesthetic procedures by the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons, surgical and nonsurgical aesthetic procedures such as liposuction, breast augmentation, rhinoplasty, botox, and fillers, are at an all-time high worldwide. Of the thirty million aesthetic procedures performed by plastic surgeons in 2021, 12.8 million were surgical and 17.6 million nonsurgical, reflecting a 33 percent rise in aesthetic surgery over the last four years.

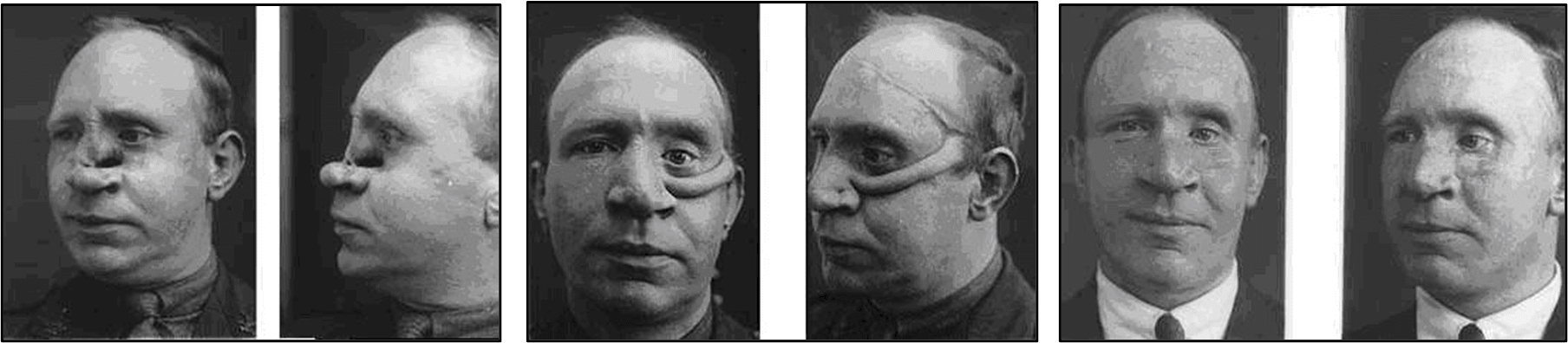

Although plastic surgery is commonly associated with aesthetic surgery, it originated as a reconstructive surgical specialty. When plastic surgery was established in the late 1800s, traumatic injuries sustained during war were the driving force for advances in plastic surgery and aesthetic procedures did not exist.

After World Wars I and II, pioneering surgeons such as Sir Harold Gillies and Archibald McIndoe developed reconstructive surgical techniques to restore form and function to military personnel who had suffered severe facial burns. Media coverage of their work in 1942 gained public interest.

There has been a 33 percent rise in aesthetic surgery over the last four years

The first aesthetic procedure was not performed until two decades later, in 1962, when a woman in Texas became the first person to receive silicone breast implants.

Today, the aesthetic procedures industry has grown and continues to evolve in many parts of the world to meet the increasing demands of cultural trends. The United States and Brazil lead with the most plastic surgeons (7,500 and 6,000, respectively) and the most aesthetic surgical output globally.

The Unmet Burden of Reconstructive Surgery

Reconstructive surgery, plastic surgery's raison d'etre, aims to restore form and function to the body. Since the pioneering procedures of the twentieth-century wartimes, reconstructive surgery today treats a wide range of conditions and patients, from newborn babies to the elderly. Conditions requiring reconstructive surgery include those present at birth, such as cleft lip and palate, as well as acquired conditions such as cancer, traumatic injuries, burns, and destructive infections.

Despite significant advancements in aesthetic procedures, the global need for reconstructive procedures is not being met. Health systems in most high-income countries can meet the reconstructive surgical needs of their patients, but the same cannot be said of many low- and middle-income countries. For example, more than 95 percent of the population in South Asia and central, eastern, and western sub-Saharan Africa do not have access to safe affordable surgical and anesthesia care.

Patients in LMICs face many geographic and financial challenges to seeking, reaching, and receiving care. Those able to reach a hospital often find that it does not have a plastic surgeon or anaesthetist, or that the operating room does not have the right equipment or supplies.

Only 12 percent of the specialist surgical workforce practice in Africa and Southeast Asia, where 33 percent of the world's population lives. Malawi, a LMIC, with a population of twenty million, has only three plastic surgeons. By contrast, Los Angeles County, population 9.8 million, has hundreds.

Numerous nongovernment organizations (NGOs) have been involved in providing reconstructive surgery in LMICs for decades. Traditionally, this involved flying in a surgical team with equipment and supplies, operating on patients over a few weeks and leaving postoperatively. Even though this approach has helped reduce some backlog and provided benefit to individual patients, the model has been challenged for not providing sustainable benefits to local health systems. Further, it can be disruptive to an already strained health system and involve uneven power dynamics.

The involvement of NGOs, international professional societies, and high-income academic surgical centers should have an impact and be sustainable. Participation in short-term reconstructive interventions in LMICs should occur within the framework of long-term, demand-driven commitments focused on local capacity-building and health systems strengthening.

This has been recognized and transitions have occurred within NGOs and other actors involved toward more sustainable solutions.

Malawi, a LMIC, with a population of twenty million, has only three plastic surgeons

For example, NGO Operation Smile's collaboration and investments in health systems strengthening through cleft lip and palate surgery support locally led cleft lip and palate centers in Colombia, India, Paraguay, the Philippines, and other countries that function year-round. Partnerships with local universities, hospitals, ministries of health, and regional accreditation bodies have facilitated the training of new plastic and reconstructive surgeons in countries such as Rwanda, and the training of cleft lip and palate surgeons in other LMICs.

The roles of visiting reconstructive plastic surgeons should be aligned with locally led goals to provide sustainable local workforce expansion in LMICs. A sustainable educational focus on any short-term surgical intervention should always be present. Visiting surgeons should have the appropriate experience to fulfill clearly defined, locally led educational goals to build local surgeon workforce capacity.

This requires long-term commitment from participating surgeons in ongoing technical exchanges and collaboration. Ideally, such educational endeavors should align with coexisting sustainable investments in health systems strengthening and with national health policy objectives.

As the aesthetic industry grows, let's not forget the reconstructive origin ethos of plastic surgery. The benefits of reconstructive surgery should be reaching all children and adults around the world in need of essential reconstructive surgery.

Further evolution of short-term reconstructive programs, such as those provided by NGOs, is required to sustainably reduce reconstructive surgery burdens in LMICs. Such interventions should occur within the framework of long-term, demand-driven commitments focused on local capacity-building and health systems strengthening that are aligned with local health-care priorities.