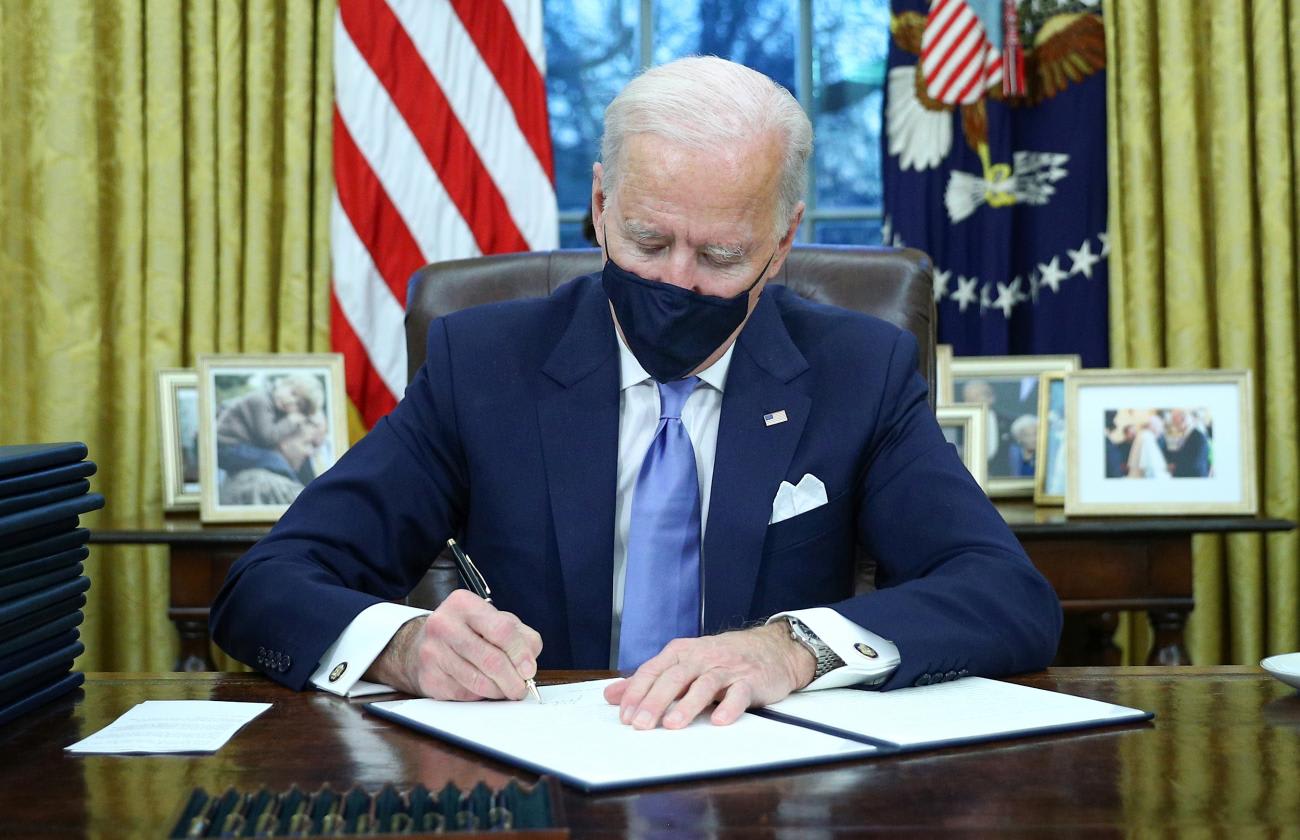

The inauguration of every new U.S. president is an ending and a beginning. The administration of the oath of office to Joe Biden on January 20th marked the most ignominious ending and inauspicious beginning of any such inauguration in living memory. President Biden assumes office facing a raging pandemic, a politically divided country, a suffering economy, and a world damaged by failed U.S. leadership. The Biden administration will transform American policies, and changes are urgently needed in global health. The administration's re-engagement with the World Health Organization (WHO) and its commitment to support the global effort to distribute COVID-19 vaccines to low-income countries begins that transformation.

President Biden's efforts to restore U.S. leadership in global health will harken back to when the United States treated global health as important in its foreign policy. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted—and continues to inflict—health policy carnage that fundamentally changes the context for global health as a foreign policy issue for the United States.

Biden's efforts to restore U.S. leadership in global health will harken back to when the country treated global health as important in foreign policy

First, in addition to the illness and death the coronavirus has directly caused, the pandemic has damaged efforts to address other infectious diseases, mitigate non-communicable diseases, support health-related development goals, reduce health inequities, and advance universal health care. This collateral damage could set many global health endeavors back decades. The scale of the wreckage cannot be ignored, but it will force foreign-policy triage in the allocation of political and economic capital, with pandemic preparedness becoming the priority. Before COVID-19, many major problems, particularly non-communicable diseases, struggled to gain attention and funding, and the pandemic will make that struggle more difficult. A politically polarized United States must also address domestic health problems that the pandemic exposed, which will limit the political bandwidth and financial resources available for global health and reinforce a focus on pandemic threats to the United States.

Second, the pandemic amplified forces, including nationalism and authoritarianism, that have weakened cooperation within a liberal international order on many challenges, including global health. Despite decades of international efforts to prepare for pandemics, poor cooperation arose on, among other things, sharing information transparently, coordinating travel measures, allocating vaccine supplies, managing medical equipment and ingredient supply chains, and demonstrating intergovernmental leadership. The web of cooperative mechanisms associated with global health governance proved no match for the nationalistic politics that the pandemic stoked and that, in turn, exacerbated the pandemic

Third, the pandemic demonstrated that global health will not escape the consequences of the return of balance-of-power politics in international relations. The manner in which China and the United States perceived the coronavirus crisis through the lens of geopolitics reflects a change in the distribution of power in the international system that will continue to affect how countries engage in global health diplomacy. Global health will be increasingly competitive rather than collaborative, especially for those issues that will garner the most attention in the wake of COVID-19, such as pandemic preparedness. Such competition will, in turn, adversely affect the machinery of global health cooperation, including the WHO, and contribute to the marginalization of global health problems unimportant in balance-of-power calculations, including non-communicable diseases.

In sum, U.S. foreign policy now confronts much worse global health problems, badly damaged mechanisms for international cooperation on such problems, and a geopolitical environment that will cause friction for efforts to improve global health governance. This daunting context does not counsel against the administration being bold; it does mean that the administration needs to be more strategic than the U.S. government was in the heyday of its leadership in global health during the Bush and Obama administrations.

U.S. foreign policy now confronts much worse global health problems

Early moves, such as re-engaging with the WHO and supporting efforts to increase access to COVID-19 vaccines for low-income countries, are important but do not, in themselves, constitute a strategy for global health distinct from what the United States has done in the past. WHO membership did not prevent the United States from being unprepared for a pandemic, nor did it have any effect on China's calculations about the crisis. The United States supported more equitable vaccine access during the H1N1 influenza pandemic as well, but it faced domestic challenges that undercut its promises.

This unforgiving context will relentlessly push the Biden administration to focus even more narrowly on pandemic preparedness than the United States did in the past. The greatest challenge for a new approach for U.S. foreign policy on global health will be how to build a renewed commitment to health security into a strategy that seeks to improve health across core foreign policy interests in economic recovery, climate change, sustainable development, and democratic renewal around the world. With a new presidential inauguration completed, it is time to begin.