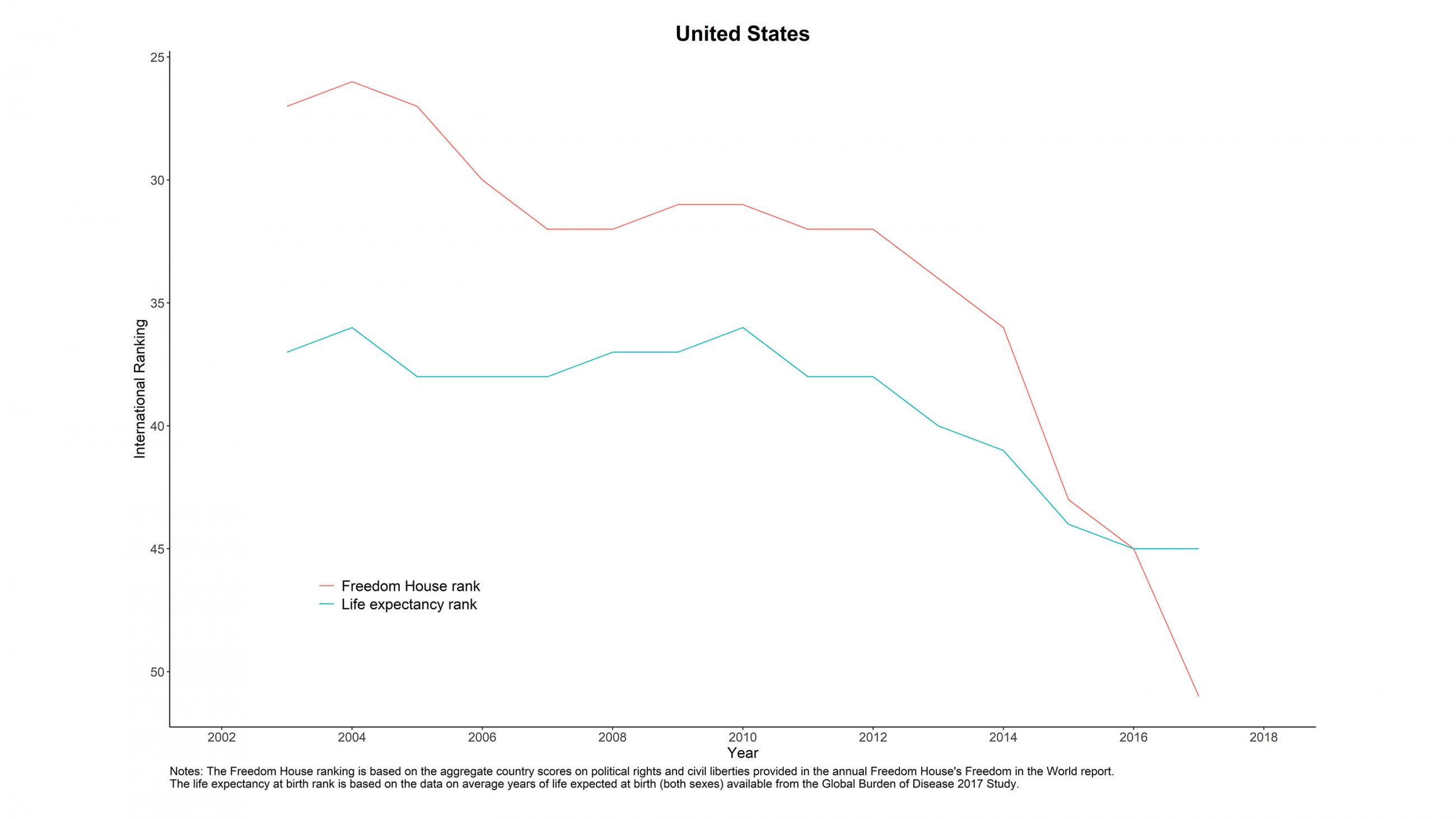

In the United States, life expectancy stopped increasing in 2010 and has been decreasing since 2014, a streak of deteriorating health not seen in this country since the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918. The decline in American health has occurred despite a growing U.S. economy when most would expect health to improve and at a time when longevity has been steadily advanced across most wealthy nations. The recent decline in U.S. health is all the more striking because it comes after decades of steady health gains, in which the average life expectancy for Americans improved by eight years and their death rate fell 42 percent between 1970 and 2010.

The politics of Americans has been declining alongside their health. Over the last decade, the United States has been falling faster than any other major Western democracy in Freedom House's ratings of political rights and civil liberties, from thirty-first place in 2010 to forty-fifth in 2016 to fifty-first in 2018. This year, the United States made the University of Gothenburg's Varieties of Democracy Project list of autocratizing nations—democracies officially designated as deteriorating.

Reversing the declines in U.S. democracy and in U.S. health depends on recognizing that they are related. Democracy is sustainable when its constituents believe that the system will work over the long run to raise living standards and create a more healthful, more prosperous, and fairer society. When that belief waivers, the groups within that democracy no longer share a stake in safeguarding the system and become susceptible to the appeals of quicker fixes and populism. It is a diagnosis borne out by the experiences of other nations suffering similar afflictions as the United States.

Newspaper slogans notwithstanding, democracy does not die in the darkness very often anymore. It dies in the light, one election at a time, with voters embracing populists who promise to cut the red tape and deliver the better life that democracy is failing to provide.

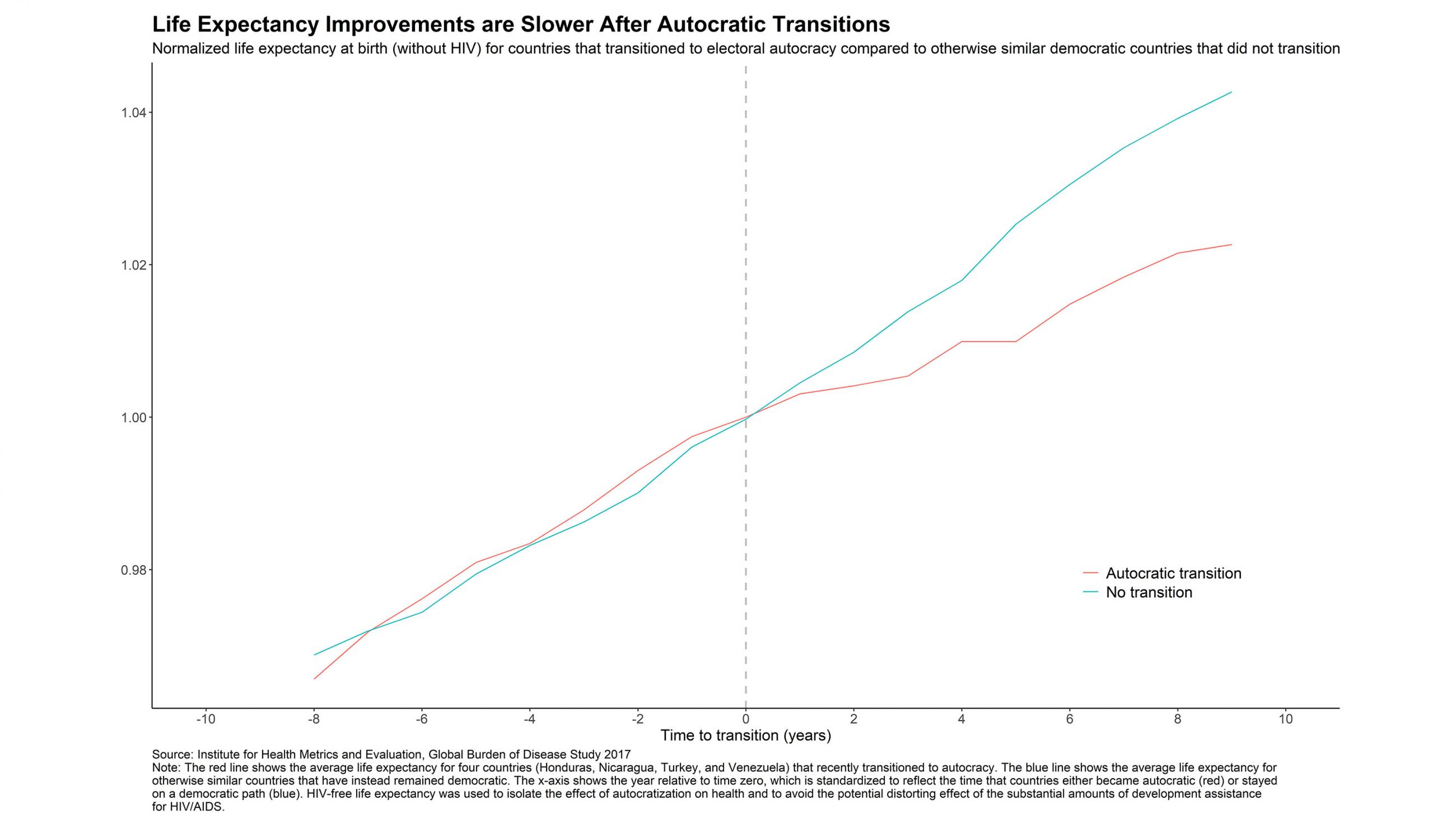

The unhealthful effects of autocracy remain robust even when accounting for economic differences.

It was not midnight military coups or dark backroom deals that brought strongmen to power in Nicaragua, Turkey, and Venezuela, former democracies that have joined the ranks of the world's autocracies. Everyday frustrations over high health-care costs, poor performing schools, corrupt politicians, and crumbling bridges drove voters in those countries to elect populists. Once in power, those populist leaders openly and steadily undermined the fair elections, free media, and institutional restraints that are hallmarks of democracy, cheered by supporters hungry for results.

Voters may turn to autocracy for better results, but, at least with regard to health, they are not rewarded for doing so. The Council on Foreign Relations published a study last week that shows life expectancy has declined 2 percent on average in Nicaragua, Turkey, Honduras, and Venezuela relative to democracies that have not transitioned to autocracy. The unhealthful effects of autocracy remain robust even when accounting for economic differences and excluding Venezuela and its collapsing health care system. Without pressure from fair elections or accountability to a free media, autocratic leaders have less incentive than their democratic counterparts to engage in the hard work of sustaining health-care infrastructure and improving care for chronic diseases. Instead, autocrats exploit ethnic and class divisions and resort to patronage to keep power.

Americans should take heed of this pattern. According to a 2018 Pew Research Center poll, 58 percent of Americans are dissatisfied with how democracy is working for them, up from 51 percent the prior year. The vast majority of those respondents expressing dissatisfaction with democracy also reported feeling pessimistic about their opportunities to improve their living standard.

In the 2016 U.S. presidential election, health proved to be a remarkably good indicator of which counties were more likely to shift their votes to Donald Trump, a political outsider promising that only he could deliver a better life. One study found that a combined measurement of life expectancy and prevalence of diabetes, suicide, heavy drinking, physical inactivity, and obesity was a better predictor of votes for Mr. Trump than race, educational attainment, employment, or income. Another study found widening health inequities were likewise a strong predictor of shifts in voting in 2016 from past U.S. presidential elections.

Health is a cause of that cumulative disadvantage as well as its leading symptom.

Health is a good political indicator because it is both a consequence and a cause of the broader dissatisfaction with American democracy. After decades of improvements, the reductions in the U.S. death rate for adults, ages 20 to 55 years, slowed in 2000 and, for some populations, began to reverse. Higher prevalence of obesity and slower gains against cancer and cardiovascular disease contributed, but the main causes were heavy drinking, suicide, and the emerging opioid abuse epidemic. The economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton attribute the rise in these "diseases of despair" to deindustrialization and associated declines in employment, income, marriage, and education—a "cumulative disadvantage" that, according to Case and Deaton, is especially prevalent among whites without a college degree.

Health is a cause of that cumulative disadvantage as well as its leading symptom. High health-care bills and catastrophic medical expenditures are major sources of financial insecurity and impoverishment for American families. Rising U.S. drug prices disproportionately affect the uninsured and people with high-deductible insurance plans, contributing to economic inequality.

The decline in U.S. health predates the Trump administration, but if Americans turned to this President for relief, most are still waiting. Annual U.S. drug overdose deaths declined from 72,287 in December 2017 to 69,366 in January 2019, but suicides rose and average U.S. life expectancy has continued to fall. For the first time since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, the numbers of Americans without health insurance increased in 2018, to 27.5 million or 8.5 percent of the population.

U.S. population that was uninsured in 2018

Health care is again on the U.S. ballot in 2020. It is the only concern that a majority of Americans agree is extremely important in the 2020 presidential election, according to a recent CNN poll. U.S. voters and politicians should learn the lessons from abroad. Be wary of populists promising to deliver better health by undermining the accountability, messy compromise, and slow consensus building that democracies require. Understand that the threats to democracy can come from the right as well as left. Most importantly, whichever U.S. presidential candidate prevails, they should recognize that the health of American democracy may depend on its ability to deliver more affordable and equitable health to its constituents.