From the outset, COVID-19 was labelled a problem primarily for older people. For example, early in the epidemic in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggested older people shelter-in-place while younger people were still crowding on beaches and gathering in bars. From the fast rise in cases that followed, the realization that these recommendations were misguided was too late. Though one woman at a rally explicitly suggested sacrificing the weak, we can revisit the ageist focus and avoid decisions that exclude older people while ignoring the risk to the young. Everyone has a role to play in combatting COVID-19.

Systematic stereotypes that portray older people as uniformly weaker, with physical and mental decline are long known

Ageism harmfully manifested in COVID-19 mandates, attitudes and health-care decision-making. Systematic stereotypes that portray older people as uniformly weaker, with physical and mental decline are long known. In the absence of other information, age becomes a default to define those who are more or less healthy, and more or less deserving. Public health policy can be particularly harmful when subpopulations believe they are not at risk simply because they were not the target of a policy. Governor Andrew Cuomo's early order requiring those above age seventy to stay home and limit visitation was ineffective to stop the explosion of COVID-19 in New York State. While well-intentioned, it contributed to portraying COVID-19 as a problem for older people. Across the United States, younger people accounted for a rise in cases and fell seriously ill or died at higher rates than initially expected.

A less ageist, more ethical approach should aim to support older people rather than accept their participation as impossible. Older people face specific challenges such as accessing everything from usual services to food and drugs as well as the increased psychological risk of isolation and infection. Ageist policies directly cause or exacerbate such difficulties. One third of U.S. doctors are above age sixty. But personal protective equipment was provided for all staff (notwithstanding the shortages), regardless of age, to reduce their risk. Similarly, public health policy should support all rather than exclude some. To reduce the overall burden of heart disease, encouraging everyone to lower cholesterol and blood pressure works better than focusing only on those with a higher chance of developing heart disease. Protecting people at all risk levels requires a full population effort.

One third of U.S. doctors are above age sixty

Another way in which ageism manifests itself is in treatment decisions, which can make the difference between life or death. Age can become default exclusionary criterion for care in real-time decision making, precluding access to life-saving resources. This was a concern in Florida where lack of standardized guidance threatened to put decision-making on healthcare providers in real-time. This prompted calls for more transparency from groups including the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) to avoid discrimination. Though not documented in the U.S., these exact concerns manifested in Europe. For example, in Italy, where guidance was initially absent, life and death decisions often hinged on the patient's age.

Drawing from standardized guidelines could help to allocate medical resources in times of crisis where real-time decisions default to age. In Maryland, age was only included as a final tiebreaker for life-saving resources rather than as an initial determining factor after public consultation. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center framework currently gaining traction has an eight-point priority score based on sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores and survival probabilities regardless of age. Age matters in terms of assigning a "heightened priority" rather than going into the score directly. Other frameworks omit age altogether. The ventilator allocation guidelines in New York's 2015 recommendations consider co-morbidities, mortality risk, SOFA, and time trials and suggests entering patients with tied scores in a lottery. Organ transplant guidelines slant toward those with greater life expectancy alongside many other considerations such as previous transplant failures.

Nearly 1/6 of the U.S. population is already sixty-five years or older, which will grow to a quarter or a third by 2030

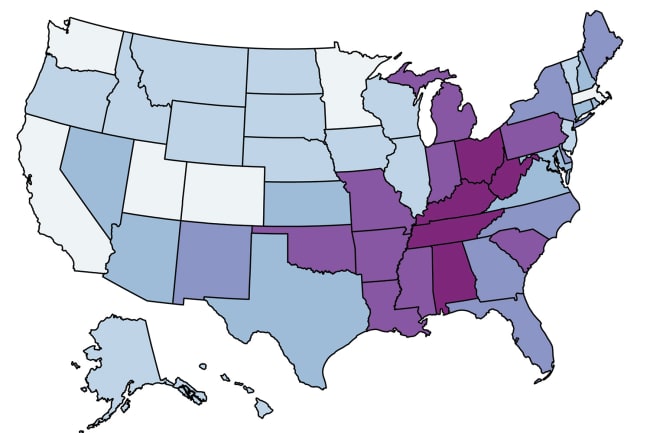

Older people are undoubtedly hardest hit by COVID-19. In the United States, those over age sixty-five are hospitalized at least four times more than eighteen- to forty-nine-year-olds. However, nearly one sixth of the population is already sixty-five years or older, which will grow to a quarter or a third by 2030. Exclusion is not a sustainable option. We can better check the ageism underlying the course of COVID-19 by underpinning policy with strategies demonstrated to reduce everyone's risk. The tide has turned in this direction as, for example, more states have general mandates to wear face masks. Though rhetoric has focused on older people, the problem is really one for all of us.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author is employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which produced the population forecasts described in this article. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.