New cases of HIV/AIDS, as well as deaths from the disease, have been nearly cut in half since 2000 due to the expansion of access to care and treatment for the disease. In low- and middle-income countries, a huge scale up in investments by donors and national governments has made this progress possible, increasing from $4 billion in 2000 to nearly $20 billion in 2016. In 2016, almost half of that funding came from donors (46 percent). Donor funding for HIV is tenuous, however, and fell by 20 percent between 2012 and 2016. Should donor funding decline further, there are many low-and middle-income countries that can't afford to make up the difference, and up to 5 million people living with HIV/AIDS who are currently on treatment could be forced to face the impossible choice of somehow finding a way to pay out of pocket for care they cannot afford or to stop taking their medications altogether.

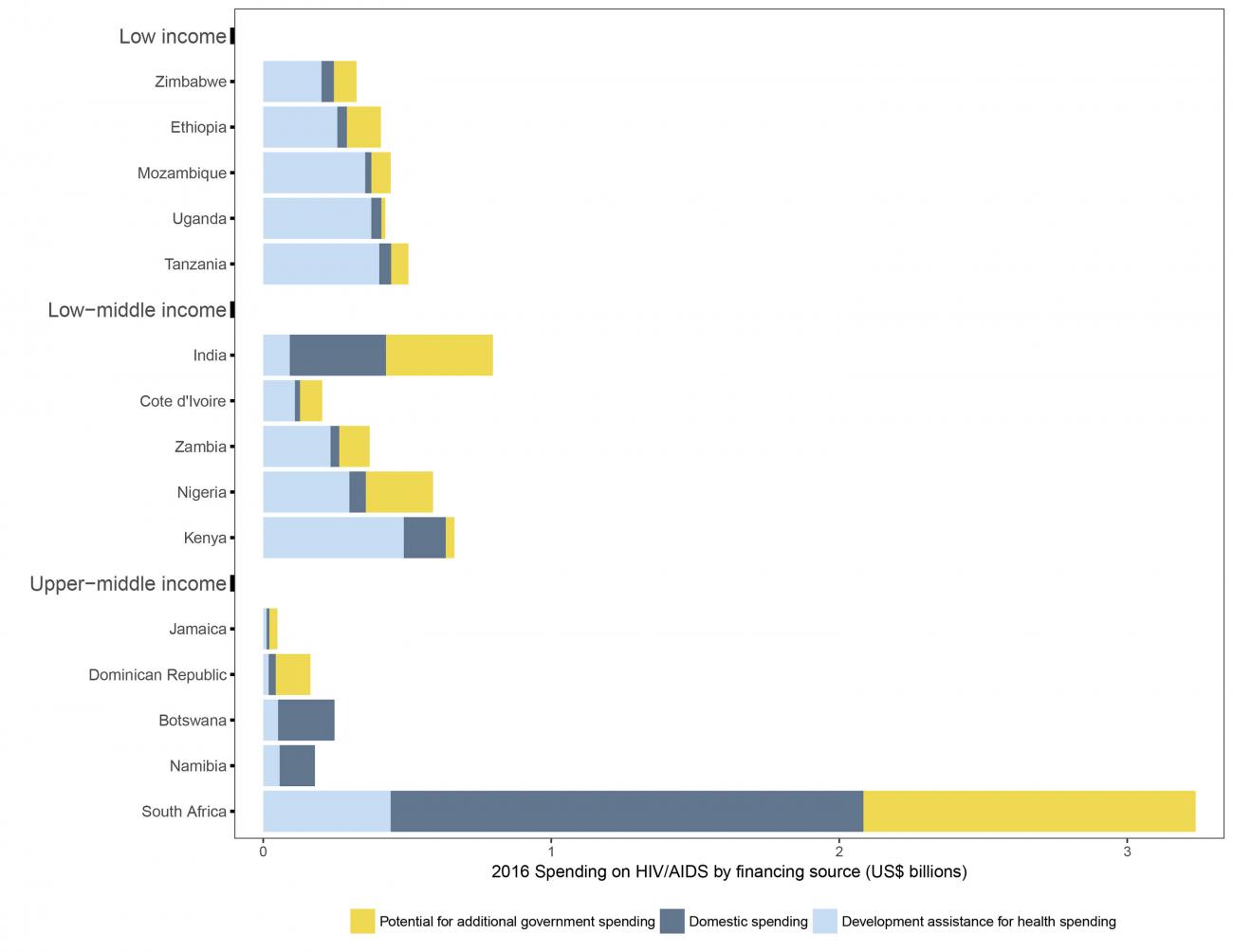

A recent analysis by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington in Seattle, Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the Kaiser Family Foundation, headquartered in San Francisco, California, showed that the situation may be even worse when you look specifically at low-income counties. Approximately 85 percent of HIV/AIDS spending in low-income countries comes from donors, and these countries have little capacity to increase their investments should donor funding decline.

Countries such as Uganda, Kenya, Botswana, and Namibia would not be able to fill even 10 percent of the funding gap for care and treatment of HIV/AIDS

The researchers estimated how much more countries could spend on HIV/AIDS based on their current government spending, their economies, and other factors. They found that countries such as Uganda (low income) and Kenya (low middle income), and Botswana and Namibia (upper middle income) would not be able to fill even 10 percent of the funding gap for care and treatment of HIV/AIDS if donor funding dropped. In the five low-income countries that receive the most donor funding for HIV/AIDS (Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Uganda, and Tanzania), researchers anticipate that countries would be able to fill less than 50 percent of any funding gap left by donors. However, this is not true in every low- and middle-income country. The researchers found that low-middle-income India and Nigeria and upper-middle-income South Africa could spend much more on HIV/AIDS.

When it comes to fighting HIV/AIDS, donor funding plays a crucial role between life and death in many low-and middle-income countries. Encouragingly, in October 2019, Global Fund donors pledged $14 billion to end the epidemics of HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria. As long as donors follow up on their pledges, low- and middle-income countries can continue to make progress against HIV/AIDS. But how long will this level of commitment from donors last?

EDITOR'S NOTES: The authors are employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which leads the Global Burden of Disease Study. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.