When is someone considered to be "old," and when, therefore, do they start seeing a greater risk for the diseases and conditions that we associate with aging populations?

Increased life expectancy at older ages can either be an opportunity or a threat to the overall welfare of populations

Angela Y. Chang, IHME

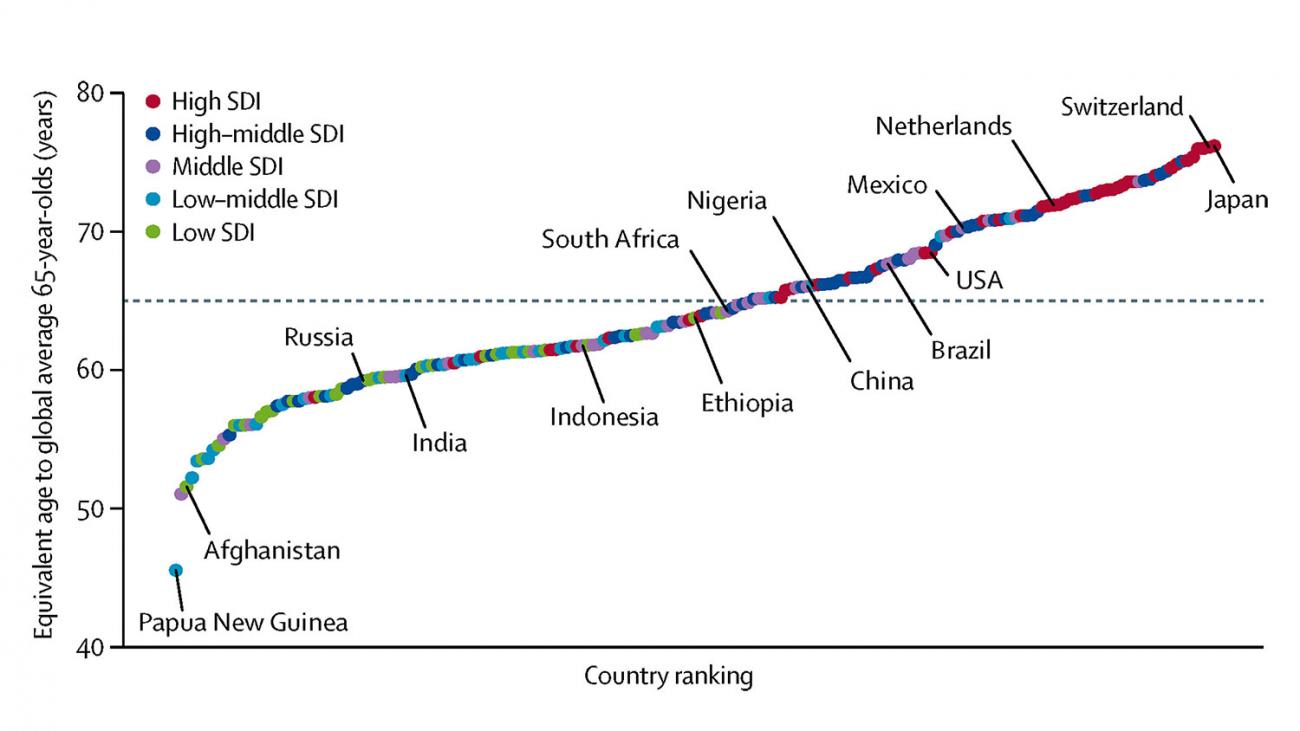

It turns out, the answer varies significantly from country to country. Earlier last spring, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) and its collaborators determined that as much as a thirty-year gap separates countries with the highest and lowest ages at which people begin to experience the health problems of a sixty-five-year-old old (see "Measuring population ageing: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017," published in the Lancet Public Health, March 2019). In Japan for instance, typical diseases associated with aging (known as "diseases of aging") such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease do not begin to emerge until age seventy-six, while in Papua New Guinea those same diseases of aging are seen among forty-six-year-olds.

"These disparate findings show that increased life expectancy at older ages can either be an opportunity or a threat to the overall welfare of populations, depending on the aging-related health problems the population experiences regardless of chronological age," my IHME colleague Angela Y. Chang, the study's lead author, said in a press release.

With increasingly older populations around the world, the relativity of aging suddenly becomes more important. Age-related health problems can lead to disproportionately higher health spending, smaller work forces, decreased productivity, and increased dependence on social services to name a few. It would follow, then, that so too should the focus of domestic policymakers and researchers on what is making older people sick, and, potentially, what is killing them.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author is employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which leads the Global Burden of Disease Study. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.

This story was updated from an earlier version to reflect the fact that Angela Chang's comment was quoted from a press release.